It might sound like something out of a Hollywood sci-fi movie — bringing a 46,000-year-old frozen worm ‘back to life’ after digging it up in Siberia.

But that is exactly what scientists revealed they had done in a landmark study published yesterday.

The experts managed to ‘resurrect’ a long-extinct roundworm from a hibernation-like state known as cryptobiosis, which allowed it to survive the harsh frozen temperatures.

Experts previously thought that roundworms could only remain in this state for less than 40 years, so the development was an eye-opening moment for the scientific world.

So, how exactly did they do it? MailOnline reveals the step-by-step process that saw scientists revive the prehistoric Panagrolaimus kolymaensis, while also looking at whether something similar could ever be done with humans.

How scientists brought worms ‘back to life’

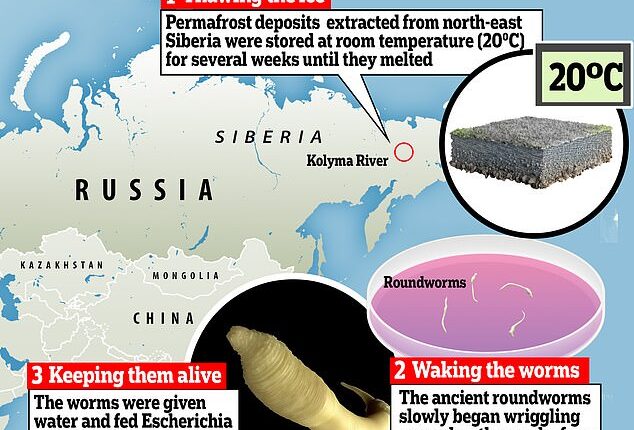

To kick off the research, scientists had to get hold of permafrost deposits containing these Panagrolaimus kolymaensis worms.

Samples were extracted from the Duvanny Yar outcrop on the Kolyma River in north-eastern Siberia in 2018.

Just two of more than 300 samples taken contained viable worms, with one of these found in a fossilised squirrel burrow and another in a glacial deposit.

These were then preserved in a laboratory for several years before scientists embarked on the testing phase of their study.

They melted the samples by keeping them at room temperature (20°C) in a petri dish for several weeks.

As the ice slowly melted, scientists began to observe the worms wriggling out, awakening from their dormant state of cryptobiosis.

Philipp Schiffer, co-author of the study told MailOnline: ‘In general you really only need to thaw the soil, like you would thaw a batch of garden soil you dig up.

‘The worms thaw along with the soil and instantly start moving – wriggling about – once thawed.

‘In other words, this is not a long process, which makes sense as these organisms live in environments where they might usually be frozen for a long winter – not millennia – and then need to wake up and make babies as soon as the sun is shining.’

Cryptobiosis is a state in which metabolic activity shuts down in response to extreme environmental conditions.

The ability is not just limited to worms, as brine shimp, plant seeds and even yeast can do this, too.

Once the worms had woken up they were fed water and Escherichia coli – a strain of human gut bacterium – to stay alive.

‘Nematodes eat bacteria. Some bacteria will have been in the permafrost soil and provided initial food,’ Schiffer said.

Could frozen humans ever be brought back to life?

While many of us dream of being frozen at their end of our lives and brought back at another time in the future, this is not yet a reality for humans.

Unlike these worms, humans cannot undergo cryptobiosis, which involves a complete or near-complete shutdown of metabolic activity.

A group of worms removed from Siberian permafrost were thawed out and came ‘back to life’

Deposits were extracted from Duvanny Yar outcrop on the Kolyma River in north-eastern Siberia in 2018

Schiffer explained: ‘In evolutionary terms it is much more a question of where and how we live and how and where worms live.

‘It would not make sense for humans to go into cryptobiosis, otherwise we might well have evolved the capability.

‘Nematodes are very small, they cannot run away from the cold, they cannot dig deep into the soil, they have no blood (keeping them warm).

‘When conditions become bad for them, they either die or need to “rest” somehow.

‘These Panagrolaimus nematodes, and other invertebrates like rotifers and tardigrades, have evolved to survive extreme conditions through cryptobiosis as a way to survive such conditions.’

As a result, Schiffer believes that bringing a caveman ‘back to life’ is currently a ‘science-fiction dream alone’.

He added: ‘We should more think about a different aspect of the story here. These nematodes have found a way to protect their DNA and cells from degrading and breaking, when they are frozen.

‘Maybe by studying the process of cryptobiosis in detail, looking specifically at which genes do what, we can find some links to human ageing and develop new drugs in this regard.’