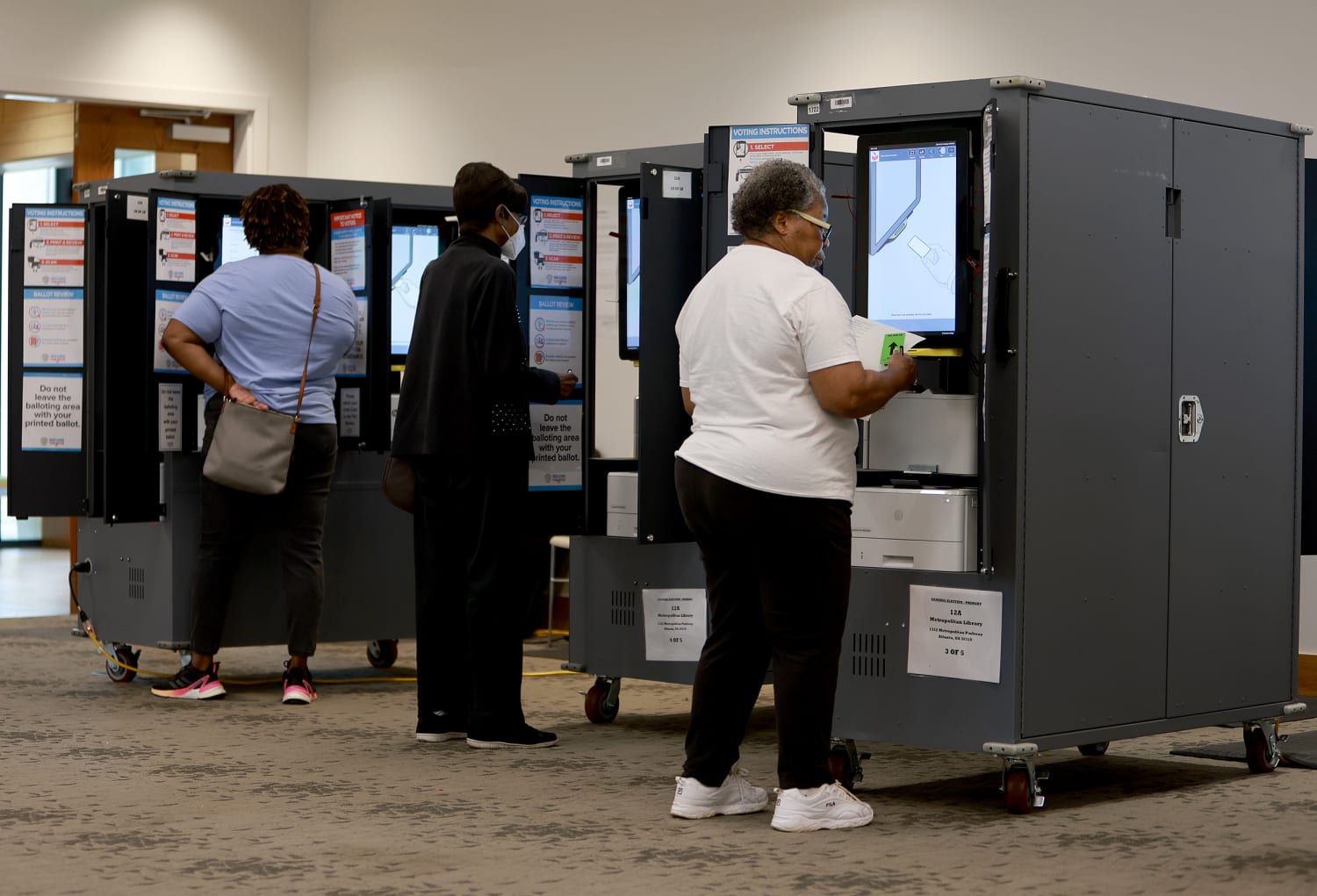

Amateur voter fraud hunters challenged 92,000 Georgia voter registrations last year, using voter rolls, public records, door-to-door canvassing and hours of their own time to ferret out the ballot rigging that election workers, courts and state officials have been unable to find.

Data from the challenges was collected by voting rights advocacy group Fair Fight Action and shared exclusively with NBC News. The group is suing in federal court over a massive, coordinated challenge to the eligibility of 364,000 people to vote in the Senate runoff in 2021, arguing that such mass challenges are discriminatory and intimidating.

The tally represents challenges in 15 of Georgia’s 159 counties — with seven of the top 10 most populous counties included — meaning the actual number in the state is likely higher.

The numbers offer a window into the impact of both baseless claims of stolen elections and Georgia’s 2021 sweeping election law. Senate Bill 202, as it is known, codified that county residents could make unlimited requests to election officials, asking them to remove voters from the rolls if the challengers believed they were ineligible. The law mandated that county officials must conduct a hearing on those challenges within 10 business days.

“S.B. 202 blocked access to the ballot and deterred voters from participating through processes like these mass voter challenges,” said Cianti Stewart-Reid, the executive director of Fair Fight. “As we think about what does voter suppression look like in 2022 — this is what it looks like.”

The vast majority of the challenges documented by Fair Fight were unsuccessful; local officials left nearly all the voters on the rolls. According to the tally, 2,208 voter registrations were removed at hearings. More than 3,500 others were moved into pending or challenged status, which requires voters to update their registrations.

But advocates and experts said the challenges created bureaucratic nightmares for busy local officials trying to run smooth elections, who were left to sort through stacks of mass challenges as they balanced the rights of voters with their legal obligation to respond quickly.

“We’re already not in a really great climate to run elections, and once you start throwing really large administrative burdens — it’s just another piece on the puzzle that makes it harder,” said Zach Manifold, elections supervisor in Gwinnett County, which received more than 47,000 voter challenges last year, according to Fair Fight’s tally.

It’s not hard. It’s just time-consuming.

— Georgia resident Karyl Asta on challenging voter registrations

Voter challenges conducted by private citizens are the latest in a growing trend of voter fraud vigilantism in which people who are convinced of widespread fraud — despite ample evidence it does not exist — have begun to take matters into their own hands. In Arizona, armed members of a right-wing group patrolled and monitored drop boxes, while in New Mexico, volunteers with an “audit force” went door-to-door seeking to check the voter rolls.

Fair Fight’s data also suggests that voters of color and younger Georgians may be disproportionately affected by mass challenges. In Cobb County, the group was able to examine voter registration data — which includes a voter’s race, ethnicity and age — for most of the challenges, and found that both demographic groups were overrepresented in the challenges.

Fair Fight, which was founded by Democrat Stacey Abrams, began tracking challenges in 2021. It followed public hearings weighing challenges and issued public records requests to get the lists of challenged voters.

The staff member overseeing Fair Fight’s tracking worked for a couple of months on the voter protection team for Abrams’ gubernatorial campaign in 2022 and continued the tracking there; she returned to work for Fair Fight after the Democrat lost.

From public records to personal experience

Fraud hunters typically use public records to mine the voter rolls for potentially ineligible voter registrations before making written requests to the local commissioners in their county. Many use change-of-address data from the U.S. Postal Service to challenge the eligibly of voters. Others have personally canvassed in their communities to examine registration addresses, according to Fair Fight’s tracking.

And while the bulk of the challenges fail, some voters receive letters informing them that someone else has challenged their eligibility.

The challenges are “more likely to disenfranchise or intimidate or confuse voters than they are to actually turn up people who are ineligible to vote,” said Andrew Garber, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law. The organization has urged counties to reject mass challenges and called on the state to establish standardized procedures for processing them.

Challenges in 2022 ranged from expansive to exacting.

- A Forsyth County resident filed one of the biggest challenges of the year in October, challenging 15,787 voters — about 6% of the county’s voter rolls — in one fell swoop. He said postal service data indicated problems with the voters’ addresses. The commissioners were skeptical, and asked whether he had tried to filter the registrations to weed out college students or military members who were forwarding their mail for those reasons. He had not, the minutes of the hearing indicate. The challenges were dismissed.

- A Cobb County resident challenged more than 60 students at Kennesaw State University who used a general college address instead of a specific dorm address on their registrations, along with dozens of registrations that appeared to lack an apartment number. The county dismissed the challenges.

- In November, a Forsyth County woman challenged the registration of the previous owner of her home, saying the person was living in Texas and improperly using her address in Georgia, according to minutes of the hearing that considered the challenge. The challenge was upheld.

The challenge laws have been on the books for years; they were designed so voters could bring their personal knowledge to officials, according to Janine Eveler, an 18-year veteran of the Cobb County elections department.

Years ago, she filed a voter challenge to get her in-laws off the voter rolls when they moved out of state.

“They knew what I was doing,” she said. “It was personal knowledge I had. The code was originally intended for that sort of thing, not for these mass challenges based on the change of address that’s been filed.”

Cobb County has set a high bar for accepting challenges, according to Eveler, but some counties have dedicated enormous manpower to investigating the challengers’ claims.

In late August, VoterGA, a group that claims widespread election fraud and corruption, worked with local residents to challenge the registrations of more than 37,500 voters in Gwinnett County — nearly 6% of the county’s voter rolls.

Gwinnett County’s Elections Supervisor Zach Manifold said he had six to 10 people working long hours, frequently 60 to 70 hours a week, for nearly a month to evaluate each challenge.

At the end of the month, the Board of Commissioners rejected the challenge as a whole. But his staff was now exhausted, Manifold said, and heading straight into its busy election season.

Many of the challenges were based on changed addresses, and he said members of his team had already reached out to those voters to update their information and, in some cases, had begun the yearslong process prescribed by federal law to remove out-of-date voter registrations from the rolls.

“I don’t think they like that, depending on where you’re at, it can take anywhere from five to nine years … before you’re actually canceled,” he said. “It’s federal law that we have to give people this much time.”

The disparity in how counties handle challenges has caught the attention of a number of advocates, including the Brennan Center and a number of Georgia voting rights groups who wrote a letter this month urging the State Election Board to create a standardized process for counties to respond to challenges.

“The upcoming election cycle will likely see more mass challenges,” the groups wrote. “By creating rules before the cycle’s administrative burdens become too intense, the board can help counties navigate a thorny law with more clarity and efficiency.”

‘I don’t have faith in any of them’

Karyl Asta, 62, doesn’t typically volunteer for campaigns or get involved in politics — though she made an exception to wave signs for Republican Herschel Walker during the recent Senate runoff — but she’s one of the Georgia residents who has spent hours poring over the state’s voter rolls in pursuit of getting ineligible voters booted.

“It’s not hard. It’s just time-consuming,” she said.

She will search for registered voters who have filed with the post office to change their address and so perhaps have moved, or examine voter rolls for registrations that lack an apartment number. She’s challenged more than a thousand voter registrations this way, she said.

Asta said she doesn’t want to disenfranchise eligible voters. She figures that if she’s wrong, people can simply reaffirm their registration or update it with election officials if sent a letter informing them of the challenge. But she wants Cobb County to do more to clean up the voter rolls and prevent fraud.

Asta said she distrusts the election system because of the errors she’s seen — like a DeKalb County ballot-counting machine programming error that occurred in a 2022 primary.

Asked if she had faith in her state’s recent election results, Asta said: “I don’t have faith in any of them.”

Back in Gwinnett, Manifold said the submissions have continued this year, though so far the challenges are less broad and more specific — “data cleanup things, instead of real mass challenges,” he said, like duplicate records.

“It’s unending, we’ve had something like nine filings since the beginning of the year,” he said. “The groups out there are still active.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com