This story is our first in a series on Black family history to celebrate Black history this February.

Growing up in Philadelphia, Amber Jackson said she knew so little of her history that she felt disconnected from who she was.

“They didn’t teach you the history of Black people in school,” she said. “They kind of gave you the illusion that Black people just showed up after everything was put together.”

Attempts to learn about her family history from older relatives were futile, she said. “I could see the hurt in their faces. They didn’t want to talk about it,” Jackson said. “So, I let it go.”

Then she saw the 2002 movie “Antwone Fisher,” about a young sailor who had been in foster care and sought to learn more about his birth family. “And that’s when I was inspired to start my search to find mine, just like he did,” Jackson said.

She said she went through the Whitepages, as actor Derrick Luke had in the movie, and located her father’s sister almost instantly and called her, which led to more relatives. The findings inspired her to learn more, and Jackson pressed on, spending hours that turned into years building out her family tree through searching archives in libraries and research centers, scanning microfilm and, as technology advanced, using online services.

In 2021, after 19 years of probing, she struck Black family tree gold: an ancestral connection to the legendary abolitionist Harriet Tubman. Jackson learned that her great-great-grandmother was Jeanette Cornish, whose grandfather was Aaron Cornish, born in 1822 in Cambridge, Maryland — the same town as Tubman.

At 17, Aaron Cornish was among the 28 enslaved people Tubman led from the plantation on which they were kept. They would later be called the Cambridge 28, famous for the size of the group that escaped to freedom while carrying weapons to defend themselves, if necessary, and enduring three days of torrential rain.

“I watched the Harriet Tubman movie in third grade, and I felt a strong connection, but I didn’t know why,” Jackson said. “Every year after that, Harriet Tubman was my only focus for my Black History Month reports.”

After confirming the findings, “I cried like a baby,” Jackson said. “Never could I imagine that my great-great-grandparents were freed and set on a path of my generation being born in Philadelphia because of her.”

The revelation elevated her self-esteem, she said, giving her a sense of self that had previously been absent.

“First, I felt pride bursting out of every pore,” she said. “Then, when I reread their story and what they went through, the emotion changed to an overwhelming hurt and sympathy for my family, imagining what my great-grandmother, Daffney, had to endure, giving birth during the escape and having enough faith and intestinal fortitude to push forward for not just her and her husband but her children. I am blown away by their strength.”

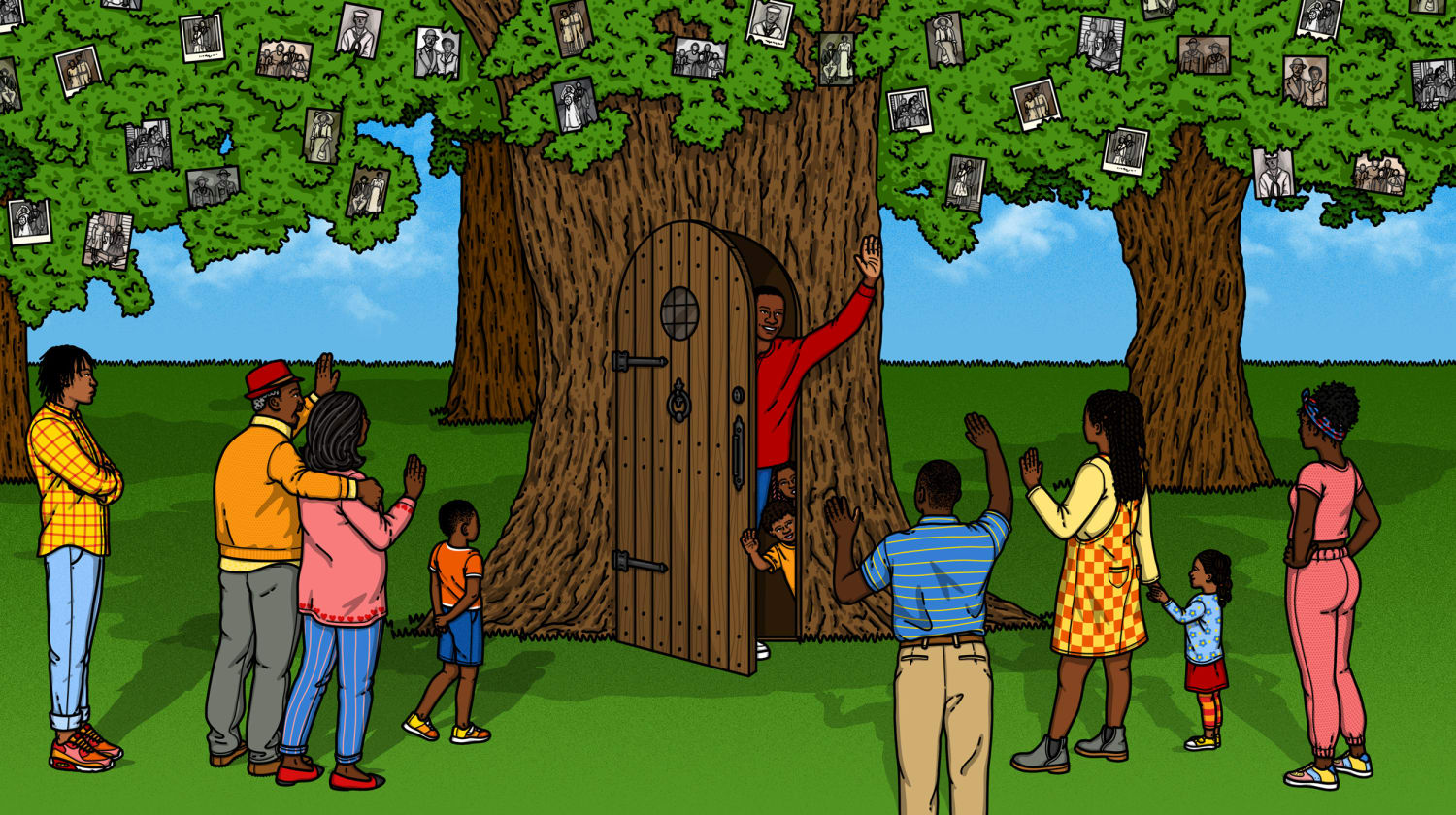

Jackson’s story underscores the surge in Black people using various means to increase their connection to family members who came before them as a way of bolstering their identity. The discovery of bloodlines generates a sense of self that can be profound — and can even alter how Black people look at themselves, Jackson said.

“Remember, Black families were separated purposefully to delete and separate any sort of throughline, any sort of emotional connection,” said Donald Grant, a clinical psychologist and the executive director of Mindful Training Solutions, a consulting firm in Los Angeles that specializes in wellness and behavioral health. “And so, because those things were deliberately severed, a lot of Black people are getting catharsis by identifying these connections that were taken from them. These search options are providing people with opportunities to get tangible examples of their historical resilience. White people have stories about their heritage in newspapers and in textbooks that support white superiority and ideology. Black people have to find information to build that history, that pride.”

‘It makes me feel real. I feel more human.’

Longtime searchers manually perused records until technology allowed for exploring on computers and cellphones. Genealogy websites like Ancestry, 23andme and African Ancestry have proliferated, giving the average person interested in obtaining at least some basic family information access to records.

The increase in Black people searching for relatives is illustrated in the rapid growth of the Facebook page Our Black Ancestry, which has grown to nearly 36,000 members in seven years. The interest in genealogy has become so prevalent that last year Ancestry.com released, free of charge, more than 3.5 million records of previously enslaved Black people, documents obtained from Freedman’s Bureau, a federal agency created in 1865 toward the end of the Civil War.

For Jackson, that hunger for knowledge turned into an unrelenting appetite to learn more. She said her daily searches that often go through the night and into the morning “give me a sense of belonging, like I didn’t just drop out of the sky. I don’t think white people wanted us to have a sense of connection to this country. But it’s like, the more I dig, the more people I find and they become real people to me, and I want to know what they did for a living, where they lived. I want to see pictures of the neighborhoods where they lived. It makes me feel real. I feel more human.”

Sharon McKinnis can relate to that. A news researcher in the Washington, D.C., area, she said although she was young when she saw the film “Roots,” based on the iconic book by Alex Haley, it planted the idea to build her family tree. She sat down with a pen and pad with her grandparents and jotted down information about relatives that had come before them.

“That is a cherished piece of paper,” she said. “I still have it tucked away in a jewelry box.”

When she got older, McKinnis used it as a guide, and her research revealed that her second great-grandmother, Olive Thomas, had been born into slavery but not confined to its ills. Once slavery ended, she made her own way.

“I found two deeds that she was a part of, and not as property,” she said. “She purchased land from two European women in Florida.

“She was a single woman, a single mom, and according to the census records, was illiterate. Yet she was able to earn enough money to buy two pieces of property. And I was just like, Oh my gosh. I’m so proud. It makes me feel connected to someone wonderful. I come from a woman who was born enslaved, and yet managed to survive it, number one, and then thrive, despite not having any education. It’s just wonderful knowing that I come from someone like that.”

Peter Sampson, of Cleveland, sought to find ancestors further back than his grandfather.

He was one of many who were inspired to dig into his family tree after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. They contend that the social justice movement spurred on by Floyd’s murder magnified the concerns of being Black in America, and therefore inspired them to look at their past for affirmation.

“We were all suffering after seeing George Floyd get killed like that,” Sampson, 56, said. “It was an affront to all Black people. I needed to make a connection to my ancestors for strength. I knew there was something in my family — in all Black people’s families — that shows our strength. I needed that connection.”

Filling in his family tree has empowered him, he said. In two years he has built out his family tree to seven generations, he said.

“It’s pretty special to have some true connection to family before you,” he said. “I found an uncle who fought in the Civil War; he fought for justice, for freedom. That’s something. It’s a shame we have to dig like we do to find it. I didn’t feel less than before I started searching for my family. But the reward of learning about them has been about pride and connection that has changed how I feel about who I am.”

Jackson and McKinnis are so enthralled and so adept at genealogy that they now help others find their relatives.

“There is so much power in seeing that family tree grow,” McKinnis said. “And I love helping people find that history. Some people may say I am obsessed with it. I would say it’s my calling. I was put on this earth to find people’s ancestors, to introduce them or reunite them. It takes a lot. There have been lots of times when it hits 2 o’clock in the morning and I say I am going to log off the computer and I keep going and now it’s 5 o’clock. And then it’s 7 o’clock. It’s hard to let go once I latch on to a trail.”

That trail, however, can also lead to findings that are not reinforcing, Grant, the psychologist, warned.

“The other side of the searches is that there is one group of us who will be exposed to some traumas when you pull up that article showing that your great-great-grandfather was lynched by a mob in South Carolina,” he said. “Everybody is not aware of what being exposed to that type of trauma can do to an individual.”

Our genes can tell an even broader story

Genealogists conduct most family searches, but Black people can learn about their family history in a much more specific way by working with geneticists.

The difference between the two: Genealogists probe family history through records, articles and other files like deeds, birth certificates and marriage licenses. Geneticists trace family history through DNA, providing a much more precise connection that can lead all the way back to Africa.

Janina Jeff, a geneticist who was the first Black person to graduate from Vanderbilt University with a doctorate in human/medical genetics, hosts the podcast “In Those Genes,” which investigates issues around commercial genetic ancestry testing and delves deeply into “how far can you go in testing,” she said.

“One of the things I love about these consumer genetic ancestry tests is us being able to find new ways to create community,” Jeff said. “Social media has so much value to Black and brown communities because we are able to create communities without barriers. These consumer ancestry tests have become an extension of that.”

Brandon Wilson, a geneticist in Charlotte, North Carolina, said he had not searched his family history yet but he planned to do so. For the moment, he is entrenched in research that can help Black people discover their ties to Africa.

His mentor, Rick Kittles, founded AfricanAncestry.com, which has collected DNA samples from tribes across the continent. Clients can then have their DNA compared with that of the tribal populations, “allowing scientists to use the best statistical probability to give you the specific tribe that you’re most directly and most closely genetically related to,” Wilson said. “That gives you a whole different resolution of your African ties.

“So, you can learn, for example, that you are of Liberian descent and of a specific tribe in Liberia — and you can request Liberian citizenship.”

Generations sharing and exchanging knowledge

One thing is certain: The mercurial ascent of Black people seeking to learn more about their family history does not seem to be slowing.

“There’s a growing sense of community pride and community awareness that’s being facilitated,” Wilson said. “And there continues to be a push of generational information sharing that’s happening between different generations of our folks who are conscious and aware of the importance of connection. It’s really bridging the gap between generations and taking the veil off a lot of stuff.”

Jackson, the Philadelphian who found family members through the Whitepages, said uniting generations evokes gratification for all involved.

“My dad didn’t grow up with his biological father, who was killed when he was a baby,” Jackson said. “I found his sister, my aunt, through the phone book. She knew of my dad but had never met him. Over two years I found other members of his dad’s side of the family. And when he turned 50, I surprised him and took him to the family reunion of his dad’s side.

“He was like a kid, so excited. All the older relatives had heard of him but didn’t know how to find him. Being able to find them and connect them with him, seeing the joy that came with those family connections for him . . . well, it was priceless.”

Follow NBCBLK on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com