The Food and Drug Administration on Thursday fully approved the Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi, amid concerns about its safety, cost and accessibility.

The move marks the first time that a drug meant to slow the progression of the disease has been granted full regulatory approval. Other approved drugs only target its symptoms.

“I don’t think we can understate the significance of this moment,” said Donna Wilcock, the assistant dean of biomedicine at the University of Kentucky.

About 6.7 million adults ages 65 and older in the United States have Alzheimer’s disease, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

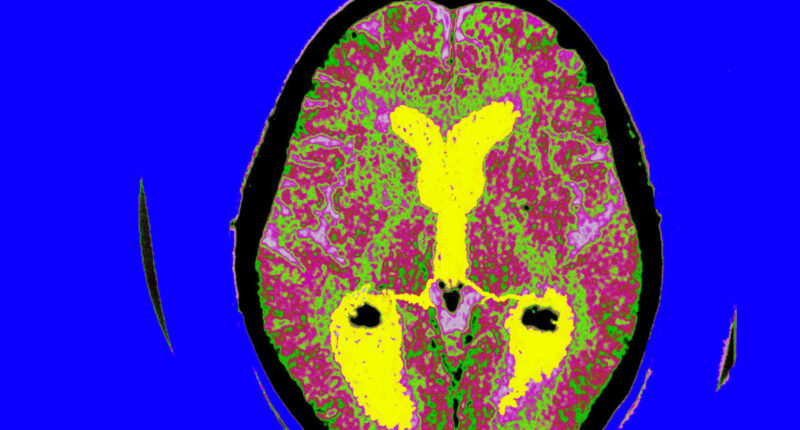

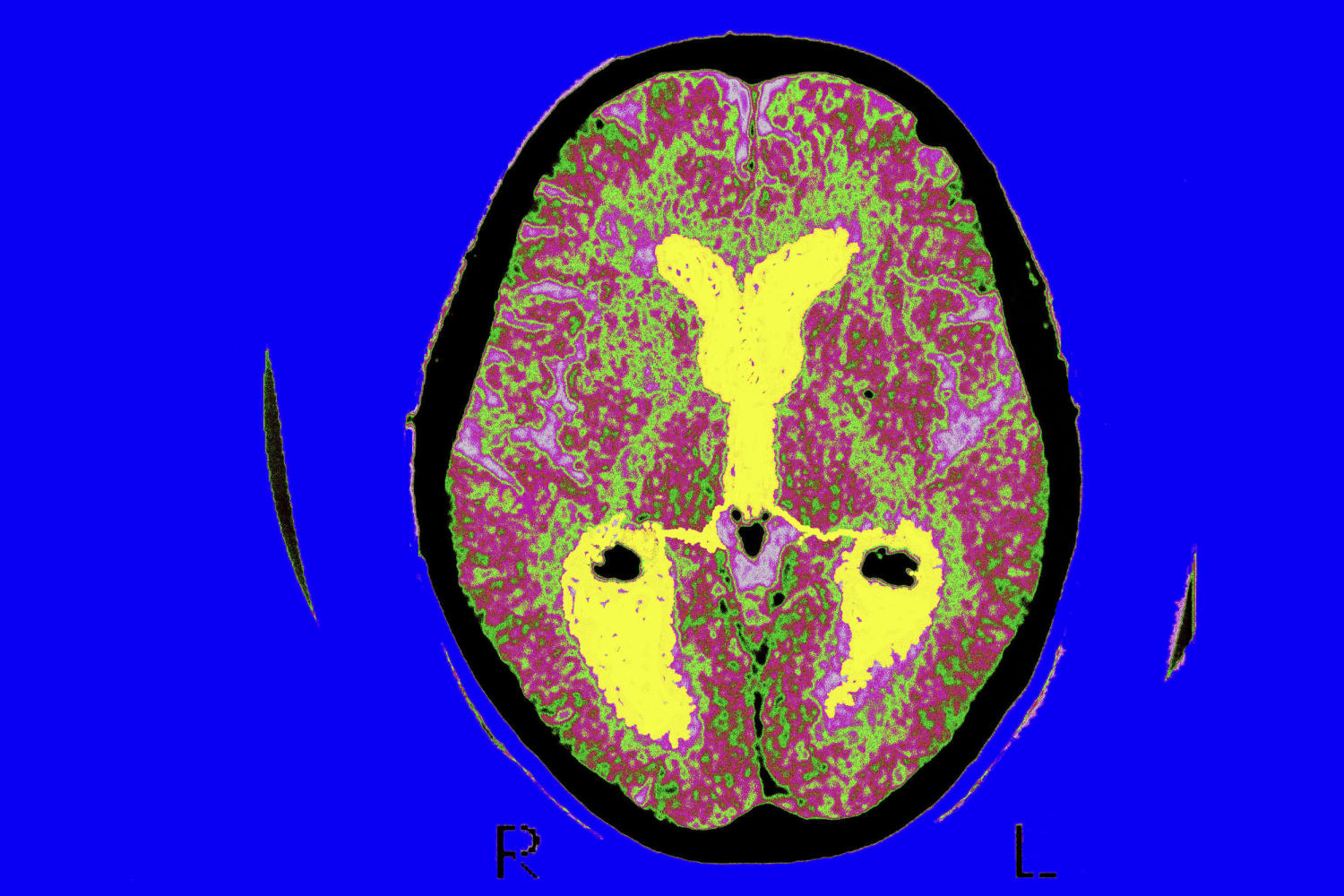

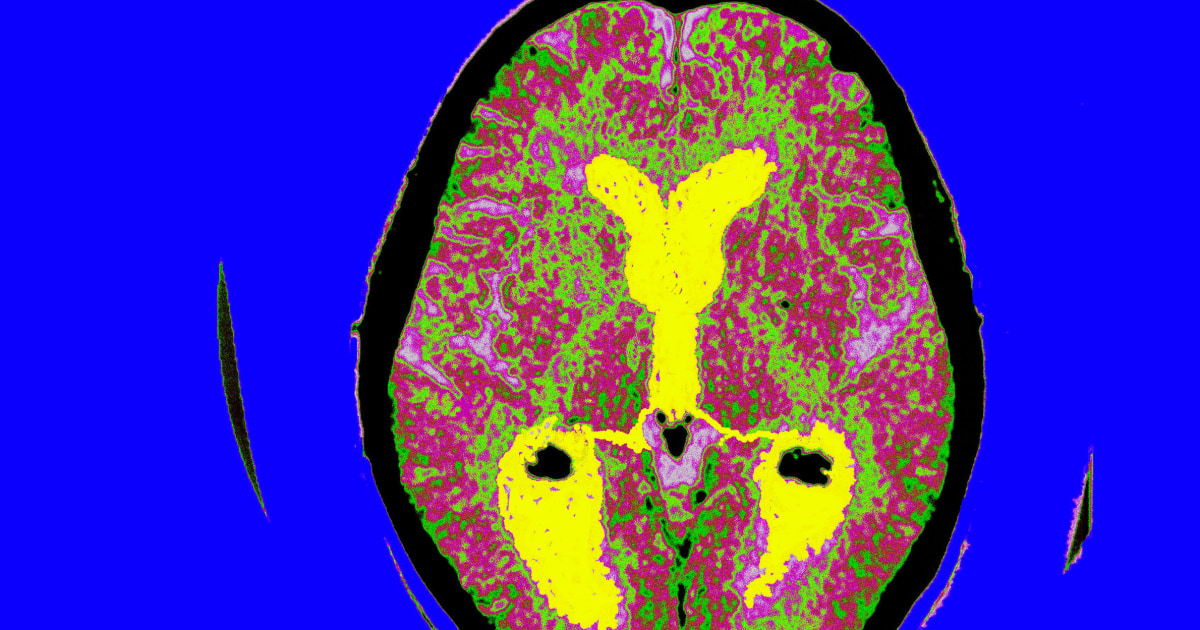

Leqembi, from Japanese drugmaker Eisai and U.S.-based drugmaker Biogen, targets a type of protein in the brain called beta-amyloid, long thought by scientists to be one of the underlying causes of Alzheimer’s disease.

In a phase 3 clinical trial of 1,795 patients with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage disease, progression of the illness was slowed by 27% over an 18-month period.

“While patients still do decline on the drug, the decline is slowed,” Wilcock said.

Dr. Ronald Petersen, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said in an email that Leqembi is not a cure, nor does it stop the disease.

“It’s a first step for hopefully more therapeutics in the future,” he said.

The Alzheimer’s Association, which has vocally advocated for the drug’s approval, praised the decision.

The treatment could “give people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s more time to maintain their independence and do the things they love,” Joanne Pike, president and CEO of the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a statement.

“This gives people more months of recognizing their spouse, children and grandchildren,” Pike said.

How does Leqembi help Alzheimer’s patients?

In the phase 3 clinical trial, researchers measured cognitive decline using a scale that focused on how well patients performed in six categories: memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care.

For each category, patients were rated on a 5-point scale: 0 is normal, 0.5 is questionable dementia and 1, 2 and 3 are mild, moderate and severe stages of dementia, respectively.

Patients in the placebo group scored, on average, 1.66 on the scale after 18 months. Those who got Leqembi scored, on average, 1.21, a 0.45 difference or 27% slower rate of decline.

“In real-world terms, this likely means more time for the patient to be living independently, enjoying their hobbies, their friends and having a better quality of life,” Wilcock said. “Time will tell how much, but the clinical trial did show significant benefit on activities of daily living measures.”

Petersen said the drug appeared to slow a patient’s decline for about five months.

Others, however, were less rosy about Leqembi’s benefits.

Dr. Alberto Espay, a neurologist at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, said that the 27% slowing in the progression of the illness falls below the threshold of what would be “noticeable” to a patient.

“The odds for brain swelling and hemorrhage are far higher than any actual improvement,” said Espay, who launched a petition in June calling for the Alzheimer’s treatment to not get full approval.

In its approval, the FDA included its strongest warning label — called a boxed warning — about these particular side effects, noting that they can lead to seizures and death.

About 12.6 % of patients who got Leqembi in the trial developed brain swelling, compared with 1.7% of those in the placebo group. About 17% of the Leqembi group experienced brain bleeds, compared with 9% in the placebo group. The side effect is also seen with another Alzheimer’s drug, Biogen’s Aduhelm, which also works by targeting amyloid in the brain.

Three deaths were also linked to the drug in the clinical trials.

Petersen said that in about 75% of people, the brain side effects, which were detected on MRI scans, did not cause symptoms.

Who will be able to get Leqembi?

Leqembi was approved for people with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage Alzheimer’s disease.

The drug is given intravenously every two weeks, meaning patients will need to go to a hospital or clinic for the infusion.

In addition, a roundtable of Alzheimer’s experts recommends patients get periodic brain scans to monitor for any side effects.

Leqembi will carry a list price of $26,500 a year.

In June, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said it planned to provide coverage for Leqembi and other drugs in its class, contingent upon receiving full FDA approval. However, the agency said it will mandate that physicians gather real-world performance data on these medications through a government database. That means that only doctors who are willing to collect this data will be able to prescribe Leqembi.

Tomas Philipson, an economist who served as a senior economic adviser to both the FDA and the CMS under former President George W. Bush, said that the rule means some patients will still not be able to afford Leqembi.

“It will limit somewhat, but it will not limit as much as what the CMS is doing to the entire class currently,” Philipson said, referring to restrictions the agency placed on drugs that had been granted a fast-tracked version of approval, also known as accelerated approval. In order to receive coverage for accelerated approval drugs, patients must be enrolled in a clinical trial.

Leqembi was initially granted accelerated approval in January, before the FDA had time to review phase 3 clinical trial results.

In June, an independent advisory committee to the FDA voted unanimously that data from the trial showed Leqembi provided a benefit to Alzheimer’s patients, recommending the agency should grant it full approval.

Leqembi’s approval is significant for patients and the health care system, said Philipson, now a professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago. He co-authored a paper in June that found delaying coverage of Leqembi and other drugs in its class could cost the U.S. more than $500 billion.

Leqembi’s full approval leapfrogged that of Biogen’s Aduhelm, which was granted accelerated approval in 2021.

That approval came despite an FDA advisory committee’s finding that the drug was unlikely to work. Later, an 18-month congressional investigation found that the FDA failed to adhere to its own standards and that its approval of Aduhelm was “rife with irregularities,” putting the agency under further scrutiny.

Aduhelm initially cost $56,000 a year, threatening to raise Medicare premiums, before the company decided to cut that total in half. With only accelerated approval, the drug is only covered by Medicare if people are enrolled in a clinical trial.

No date has been set on when the FDA could make a decision on Aduhelm’s full approval.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com