The FBI is warning of an extreme scam hitting the U.S. where criminals coerce a victim to stage their own kidnapping and film it, providing blackmail material against their own families.

The warning follows numerous similar messages issued by Chinese and Australian officials throughout 2023 and comes after the first well-documented “cyber kidnapping” case of this severity in the U.S.

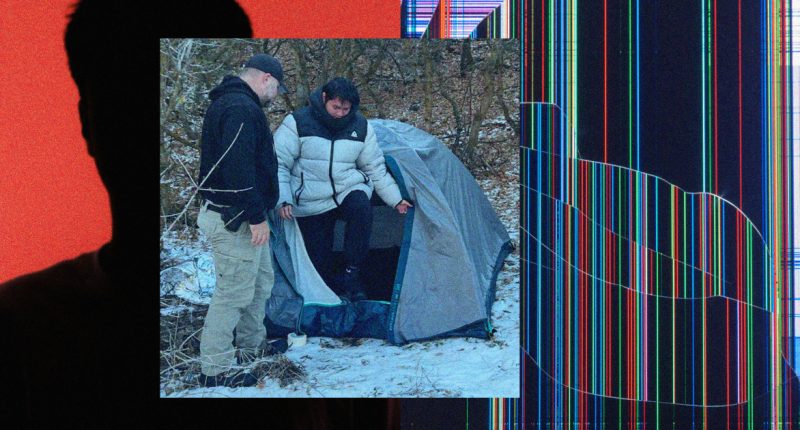

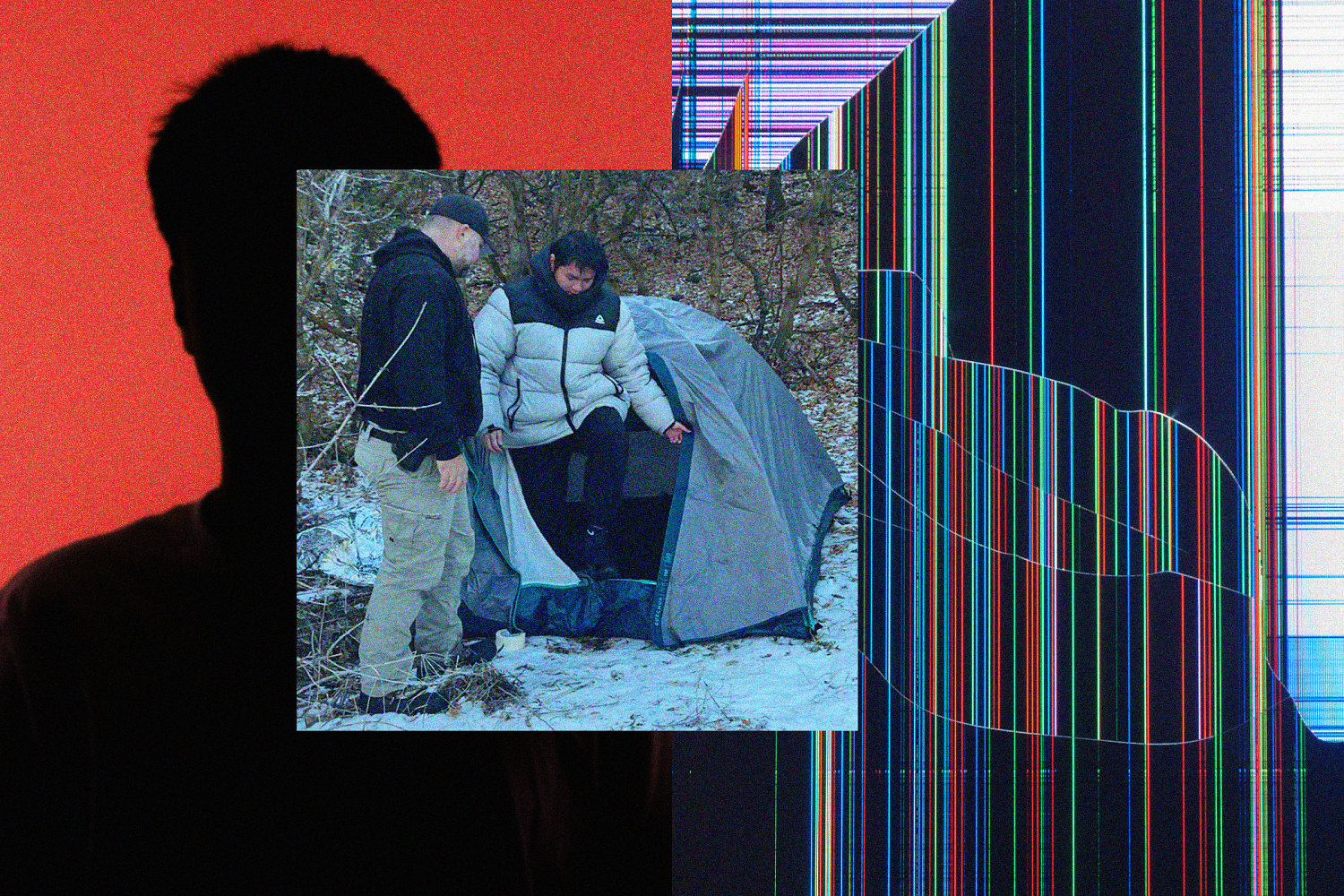

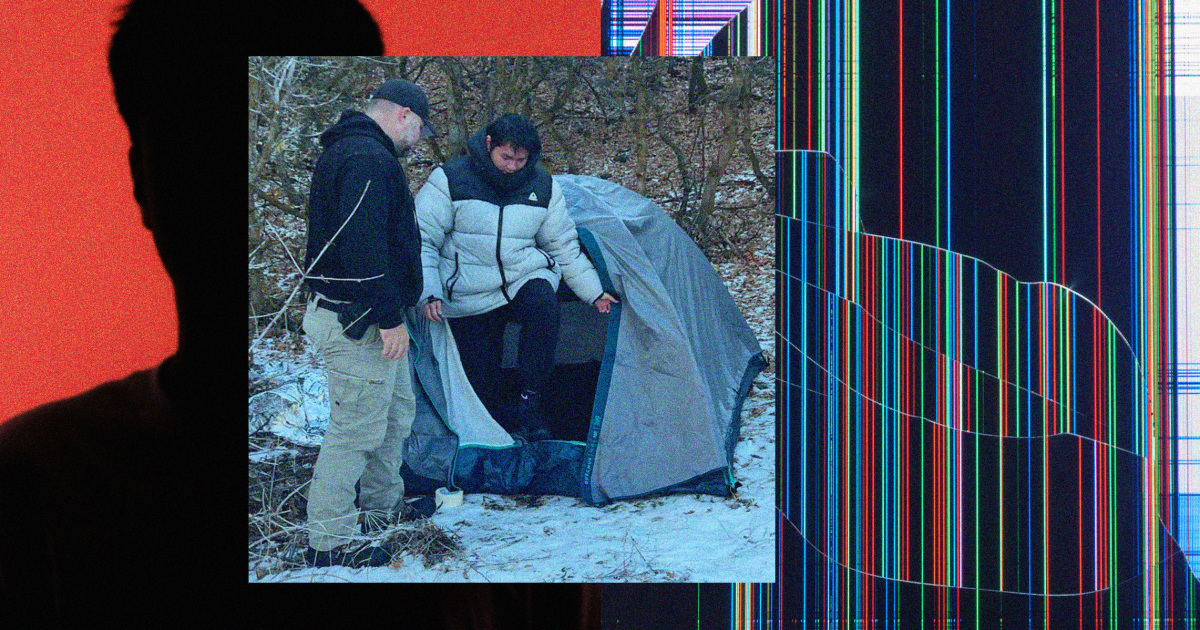

Riverdale City, Utah, police said Sunday they had located 17-year-old Kai Zhuang, a Chinese exchange student, freezing in a tent on a mountain. Police said that scammers convinced him to isolate himself and swindled his family out of $80,000.

“We believed the victim was isolating himself at the direction of the cyber kidnappers in a tent. Due to the cold weather in Utah at this time of year, we became additionally concerned for the victim’s safety in that he may freeze to death overnight,” the Riverdale Police Department said in a statement.

A spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in the U.S. said that it had dispatched personnel to the scene but that Zhuang was in good health.

In the FBI’s public service announcement, the group said that the scam usually begins with a fake call telling the victim they are being investigated by a Chinese law enforcement official. The caller then convinces them to consent to constant video and audio monitoring to demonstrate their innocence.

Then, victims are instructed to wire money to further prove their innocence or “lie to friends and family to secure additional money, to serve as a money mule, or to facilitate similar criminal schemes against other Chinese students in the United States,” according to the FBI.

“If an unknown individual contacts you to accuse you of a crime, do not release any personal identifiable or financial information and do not send any money. Cease any further contact with the individual,” the warning says.

While Zhuang’s story is the first widely known instance of the scam in the U.S., it’s more established in Australia. New South Wales police have documented Chinese students studying there falling for the scams since at least 2020, including blurred photos the victims took of themselves seemingly tied up and blindfolded. Police have even recorded a TikTok in Mandarin warning them about it.

In August, China’s Consulate in Adelaide said there had been several recent victims, costing them severe losses and trauma. China’s Consulate in Melbourne said Thursday that the scammers convinced a recent victim to leave Australia to avoid its police and travel to an unnamed third country before he realized he’d been scammed.

China’s Consulate in Toronto and Chinese embassies in the U.K. and Japan have issued similar warnings.

The most recent iteration of “cyber kidnapping” builds on a much more common scam, also known as a grandkid scam. In those scams, a victim will receive a call from a criminal impersonating a loved one, potentially with an artificial intelligence-generated voice, and claim to be in an emergency situation that requires them to immediately send money.

Online scammers can be difficult for the FBI to stop, as the criminals behind them may obscure their identity or live in countries where the U.S. has no jurisdiction.

Americans increasingly lose more money to online scams almost every year, with the FBI saying last year that victims had reported a record $10.2 billion in losses in 2022. But Chinese nationals are also prominent targets. The most financially devastating scam that targets individual Americans, known as “pig butchering,” targeted China before it became common in the U.S.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com