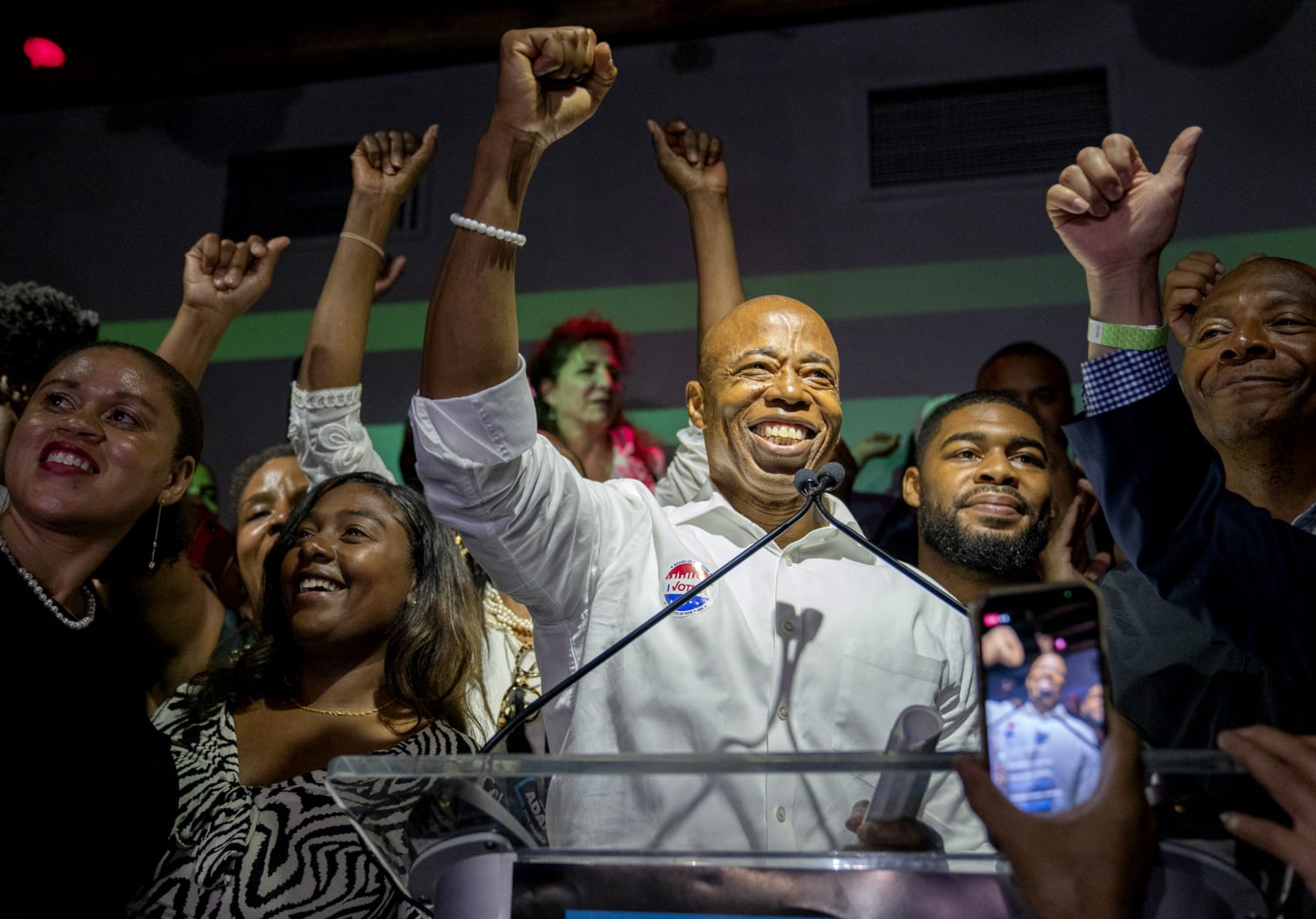

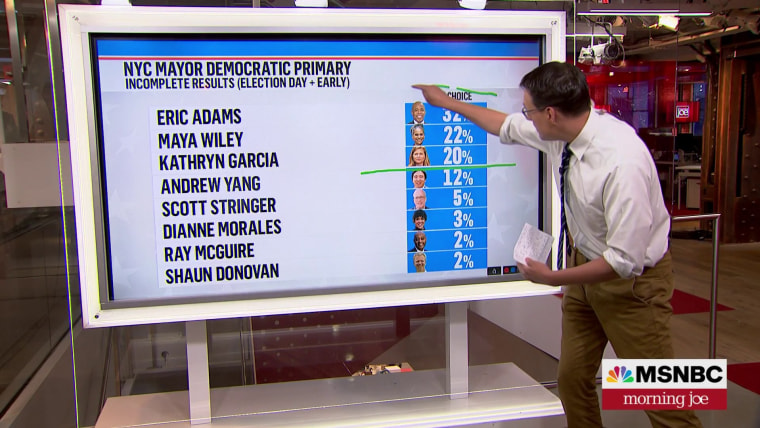

Even the day after a long, vicious mayoral campaign — which is what New York City’s Democratic primary effectively is — New Yorkers don’t know who will be their next mayor. But that’s not because the Republican primary winner stands any chance come November: It’s due to the fact that, even though Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams has a strong lead, results might take weeks to tally, thanks to the city’s new ranked-choice voting system (coupled with the standard-issue chaos at the city’s Board of Elections).

Each person who hoped to be the winner when the count is done spent the past few weeks in various brutal fights that, at times, veered into the bizarre. Former presidential candidate Andrew Yang was focused on Adams’ bathtub. Adams, a former police officer who was the front-runner, accused Yang and another candidate, ex-sanitation Commissioner Kathryn Garcia, of engaging in a plot to suppress Black and brown voters by campaigning together. The other top-tier candidate, civil rights lawyer Maya Wiley, tried to stay above the fray (with a critique on Adams’ inflammatory rhetoric).

It takes a special type of person to be drawn to a political race that all but requires bitter personal feuding to win an office that has ended multiple people’s political careers while thinking they can be the one to — somehow — break that cycle. In the last 55 years, no New York City mayor has gone on to an office higher than ambassador to Spain, though Ed Koch ran for governor and John Lindsay and Rudy Giuliani attempted runs at both the Senate and the White House. In just the past 13 years, three different New York City mayors tried, wildly unsuccessfully, to run for president.

The New York mayor’s office is a cursed fraternity; there is strong evidence that it’s impossible to leave the job without some kind of stain on your political record.

If an equal number of voters turned out as in 2016, it means anyone emerging from this year’s primary is likely to have the strong support of just about 2 percent of city residents.

So you need a unique combination of audacity, ego and aggression to run for it, even as a stepping stone. Local prankster Dennard Dayle dubbed this year’s Democratic primary a “sociopath sack race” when he unveiled a slew of mock ads that referenced just some of the issues that have plagued this field.

Adams, for instance, faced questions about past corruption allegations, issues with his taxes and even whether he actually lives in the city. Garcia and Wiley had their records in city government scrutinized. Yang, who has capitalized on his status as a political outsider, based much of his brand on a job-creation effort that failed to live up to its promise.

Below those candidates who made up the top tier, things got even worse. Current City Comptroller Scott Stringer faded from the front of the pack after allegations of sexual misconduct. Former nonprofit executive Dianne Morales allegedly created such a toxic workplace on her campaign team that she ended up being protested by her own staff. Former Housing Secretary Shaun Donovan and executive Ray McGuire spent millions of dollars, some in family money, to be met with shrugs by voters.

Amid all the months of debates, drama and attacks, though, none of the candidates managed to capture intense enthusiasm from any large swath of Democratic voters. Polls consistently showed the candidates bunched together, with none earning support from more than a quarter of the population — and that’s in a race that traditionally has low turnout. The last open mayoral primary race drew just 20 percent of enrolled voters to the polls, or about 8 percent of the city’s overall population at the time.

If an equal number of voters turns out this time, it means anyone emerging from this year’s primary is likely to have the strong support of just about 2 percent of city residents.

Campaigns have attributed the lack of voter interest to pandemic fatigue, especially since New York was among the hardest hit places in the country. But the urgency associated with the recovery makes this race even more important.

The reality for New Yorkers, though, is that there are deep institutional issues that make it hard for anyone to be optimistic about transformative action coming from City Hall.

Big Apple politics are sharp-elbowed, and if you make it to Gracie Mansion, you have earned an office that essentially has no control over one of the city’s most central — and troubled — institutions: the subway system. That is run by New York’s governor, who generally is more concerned with perceptions of his performance by those outside of the city.

Meanwhile, though affordable housing is among New Yorkers’ top concerns, every level of the city’s political landscape is fueled by money from the real estate industry, which limits the chances for real reform. (And the construction of new public housing is also out of the mayor’s hands — it’s strictly capped by federal law.)

We saw some of that play out in the race, where much of the few televised debates was dominated by discussions of crime — an issue that has been somewhat exaggerated by the nightly news broadcasts and tabloid papers. While murders were up in the city last year, that’s part of a nationwide trend that took place during the pandemic, and other crimes in New York were down. Even with last year’s violent spike, the city is nowhere near its murder rate of the first part of last decade. Nevertheless, the discussion about crime, no matter how exaggerated, crowded out any time to talk about the existential issues for most New Yorkers, which include housing, poverty and climate change.

Yet those will be the issues that will face whomever does win on day one.

New Yorkers have the reputation for thinking they’re at the center of the universe, and the mayor is the chief executive of a city with more than 8 million residents who gets more regular media attention, national and local, than almost any other mayor in the country. Yet, for all intents and purposes, this was a race that didn’t attract marquee talent and was defined by the candidates who didn’t enter it — including the face of the new progressive movement, the fifth-ranked Democrat in the House of Representatives and a state prosecutor who is one of the key figures in the investigations into former President Donald Trump.

In private conversations with some of the people who avoided the field, I have gotten a clear sense of why: It’s a high-pressure job, the spotlight is always on, the problems — particularly post-pandemic — are complicated, opponents are constantly taking potshots and in many respects your hands are tied.

Eric Adams or whoever emerges as the winner from this protracted vote count needs to overcome the negative dynamics that have plagued the office. And that can’t just be in a fight for their future ambitions; it has to be a battle that will define the way forward for a city in need of a comeback.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com