A LARGE satellite is set to plummet into Earth’s atmosphere in a matter of hours but scientists are still clueless about where it’ll end up exactly.

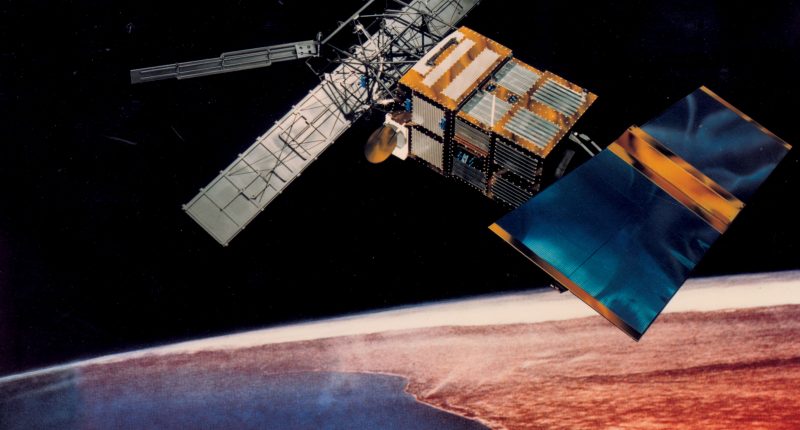

The European Space Agency’s ERS-2 satellite was launched in 1995 for an Earth observation study.

ERS-2’s Earth-observing duties were halted in 2011, when the ESA emptied its fuel tank to lower its altitude and save the hardware from a collision with other, operational, satellites.

When it was first launched, the satellite weighed 5,547 lbs (2,516kg).

Now, without the fuel, it pushes the scales to roughly 5,057 pounds (2,294kg) – that’s slightly heavier than a male Rhinoceros or a Tesla Model X.

Despite its large size, most of the satellite is expected to burn up when it enters the atmosphere.

READ MORE ON SPACE

There is still a chance that the 115lb antenna could remain intact and crash land somewhere on Earth.

The ESA decided to de–orbit the satellite to try and help reduce space junk.

This involved 66 maneuvers that used up the remaining fuel on the craft.

It was then at a lower orbit and less of a collision risk for other objects in space.

Most read in News Tech

The ESA couldn’t be sure when the satellite would fall back to Earth.

It suspected sometime within 15 years, and according to The Next Web, it’s now 13 years later.

ESA’s latest predictions suggest the is the satellite will re-enter the atmosphere at around 15:49 GMT / 10:49 EST.

Experts say the uncertainty in this prediction is now just +/- 1.76 hours.

There is always some degree of risk when it comes to space objects shooting towards Earth.

Even if the satellite doesn’t fully burn up in the atmosphere, there’s still no need to panic.

The chance of a person being hit by space debris is under one in 100 billion annually, according to the ESA.

There is a high chance that any debris will land in the ocean as water covers about 70 percent of Earth.

“.The vast majority of the satellite will burn up, and any pieces that survive will be spread out somewhat randomly over a ground track on average hundreds of kilometres long and a few tens of kilometres wide (which is why the associated risks are very, very low),” ESA said.