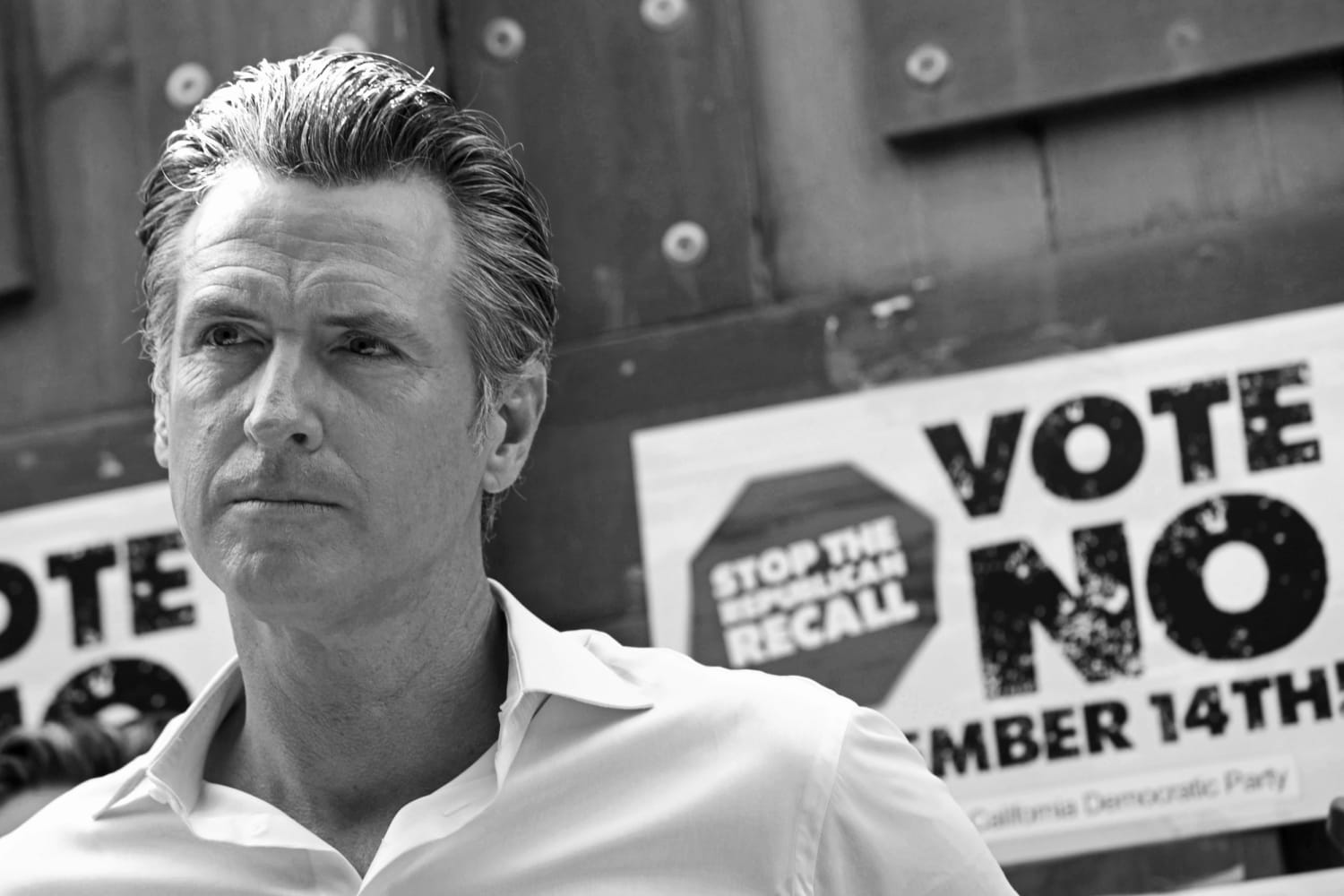

Recall fever has struck again. California is set to decide on Sept. 14 whether to kick out Gov. Gavin Newsom, the state’s second chief executive in the last 18 years, and the third governor in the nation, to face a recall vote. Voters are now paying much greater attention to the “Grand Bounce,” as the maneuver was once humorously called, and many, especially Democrats, do not like what they see.

This stamp of approval at the ballot box should matter, particularly when so many critical powers of government were not conferred by a popular vote.

The two chief objections are that recalls cut short the tenure of an official before having the full term to prove their worth and in California, specifically, that the recall mechanism allows Newsom to be voted out and then replaced by someone who receives only a plurality of the vote, which can be a very small share in a multicandidate race.

But the reality is that politicians should wade carefully into making wholesale changes to this direct democracy device. Unlike many other features of our governmental system, voters clearly like recalls, since they generally adopt them when they get a chance to in ballot measures. Progressives frequently referred to it as the “gun behind the door.” And that’s what they give us — another tool in the voter’s arsenal to control their elected officials.

The recall traces back to the early Colonial days in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was even proposed for the Constitution itself at one point, though it was voted down at the Constitutional Convention for reasons not recorded. The recall only really came back to life during the Progressive Movement at the turn of the 20th century, which pushed for numerous electoral and policy reforms throughout the country including direct democracy, direct election of U.S. senators, women’s suffrage and a federal income tax. Now 20 states have laws allowing recalls of governors.

The votes in favor of the recall have frequently been overwhelming. Only one state saw less than 55 percent vote in favor, and three of them witnessed over 80 percent of voters choosing the recall. When Arizona became a state, voters included it in their constitution only to have President William Howard Taft veto the statehood resolution over a provision allowing the recall of judges. After Arizona was later admitted without the recall, they promptly put it right back into the law.

This stamp of approval at the ballot box should matter, particularly when so many critical powers of government were not conferred by a popular vote. No voters, not even the founding fathers who wrote the Constitution, cast a ballot in favor of the creation of the filibuster, the Senate rule that allows the body to kill bills unless a supermajority agrees.

The Supreme Court’s awesome judicial review power, which allows the justices to overturn laws passed by Congress and state legislatures, as well as actions of the president, for being unconstitutional was not decided by the people but invoked by the justices themselves. The recall has had nowhere near the same effect as these two powers, yet it was specifically approved by voters, frequently against intense opposition by politicians and editorial writers.

Due to California and Wisconsin’s notorious recalls, it may seem like they are regularly used to try to overturn state elections. But that is not the case. In total, only four governors in the past century have been subjected to a recall vote. Almost all recalls in U.S. history have been on the local level. Only 39 state legislators have faced a recall vote in U.S. history, and fully one-third of those legislators were in Wisconsin in 2011-2012. In the United States, there are 7,383 state legislative seats, so in the 113 years of the recall on the state level, only a tiny fraction of officials have faced a recall.

Even on the local level, recalls are rare. Over the last decade, I have tracked about 100 or so recall elections a year, with 20 or so officials resigning in the face of a recall. Studies have suggested that there are over 500,000 elected positions in the U.S., with many eligible for a recall vote, so this works out to a negligible number.

Because of the personal nature of the recall and the sudden nature of a loss, the recall may be seen as a particularly powerful weapon. But even when it has been used successfully, it hasn’t necessarily had that strong an impact, thanks to the divided system of powers in the American government.

Eighteen years ago, many California voters were shocked to discover that the Democratic governor of the nation’s largest state, Gray Davis, was toppled and replaced by one of its biggest action stars. But it is hard to see the long-term impact of that race as anything but a footnote. Arnold Schwarzenegger did not radically change the state’s policies, nor did he reverse its increasing move to the left.

While there are certainly changes that could be made to the recall, the argument that it should be eliminated or heavily constricted runs into the powerful point that the voters want to retain this ability. They have repeatedly voted to adopt recall laws by overwhelming margins. They have used recalls to get the government they want. And they have done so without causing too much heartburn to the political process. That’s enough of a reason not to scrap the ability to hold a referendum on the powers that be.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com