Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

Walk into any hip startup and what’s the one word you’ll hear echoing across the cubicles and over the Keurig despite best efforts to rein in its use? No, it doesn’t rhyme with luck or hit. This one rhymes with hike and should be wildly familiar to anyone who’s seen the movies Valley Girl or Clueless. Like may sound juvenile, but it has taken over our linguistic nooks and crannies in almost every variety of global English. It appears at the beginning of sentences, in the middle of clauses, and now it even introduces quotes. This expanded use of like is so widespread that news outlets ranging from The Atlantic to Time to Vanity Fair to The New York Times have covered what seems to be its troubling and meteoric rise.

Related: 9 Best Practices to Improve Your Communication Skills and Become a More Effective Leader

But before condemning like as a blight on all that we hold professionally dear, let’s take some time to consider why it might actually serve the greater communicative good. Just maybe, there is more to like than we might at first believe.

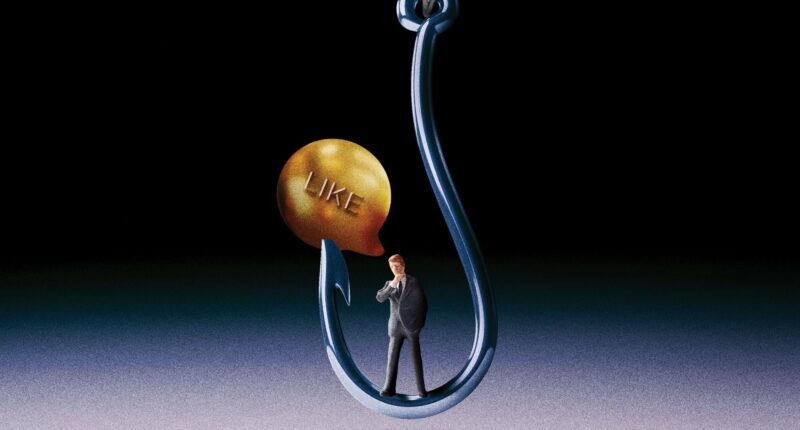

Image Credit: Nicolás Ortega

LIKE IS AN INCREDIBLY AMORPHOUS WORD. Even when it’s “appropriately” used, it’s a syntactical workhorse. Primarily, we hear like as a verb, to discuss a fondness for objects or people (“I like ice cream”). As a noun, we have preferences (likes) and their opposite (dislikes). As an adjective, the word is infinitely applicable (swanlike, buffoonlike) to mean “similar to” or “in the manner of.” We also see like used as a preposition, as found in a simile construction (“She has eyes like the sky”) and as a conjunction to embed another clause (“She rode the bike like she was on fire”).

But while these are considered the “appropriate” forms of like, they too have not always been so well received. For example, back in the 1950s, the grammar police were appalled by a cigarette ad that said, “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should.” Prescriptivists of the time denounced this “misuse” of like as a conjunction where, standardly, the word as should have reigned. (“Winston tastes good, as a cigarette should.”) Of course, those people should have been more worried about cigarettes’ long-term effects on our health rather than our grammar.

Nowadays, the conjunction like is so pervasive that its colloquial past is unknown to many of its users — even though our traditional grammar books still label that use as incorrect in formal written English.

Related: Choose Your Words Carefully to Transform Your Mindset (and Your Success)

What people complain about today is the newest type of like. In my college linguistics classes, when I ask the students to name the things that bug them the most about language, like is always at the top of the list — often comically appearing in the very sentence that denigrates it. “I hate how people, like, use like all the time,” they’ll say. Once the offending word is mentioned, the students can’t stop noticing how often it pops up in everyone’s speech for the rest of the class period — and then the rest of the day, week, month, and year. What drives this ceaseless advance? Ask most parents and they’ll probably say it has something to do with adolescent laziness or linguistic rebellion. Ask most employers and they’ll probably say it has to do with a shift from a more formal workplace to a casual, less professional setting.

Ask most linguists, though, and they’ll probably tell you we’re missing the mark.

This new like is what linguists call a “discourse marker.” English has an arsenal of these markers — such as so, you know, actually, oh, um, and I mean — that don’t directly contribute to the literal content of a sentence. Instead, they contribute to how we understand each other by providing clues to a speaker’s intentions. For instance, when I say, “Oh, I finally got a job!” my use of oh is a shorthand way to prompt a listener to mimic my surprise. Discourse markers provide the social greasing of the conversational wheel. Without them, our speech would sound more computerlike. In fact, try not using any. Not only will you find it quite difficult, but others will find you a less appealing speaker.

Related: 4 Expert-Backed Strategies for Improving Your Communication Skills

Discourse markers are by no means new or unusual. Shakespeare made liberal use of them. The epic poem Beowulf even begins with one (Hwæt!), meaning “what” in Old English, which was a signal to the audience that something worth paying attention to will follow. Old English texts from the fifth to 11th centuries are full of the word þa, meaning “then,” which seemed to serve a similar role. By the early modern period (15th through 17th centuries), interjections such as alas, ah, and fie, among others, functioned to give a sense of a speaker’s intentions or emotions (alas, ’tis true). The use of like as a conversational marker, which today’s critics often blame on modern youth, dates back centuries. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) cites an example from 1778: “Father grew quite uneasy, like, for fear of his Lordship’s taking offence.” It also cites another example from 1840, in a magazine of the era: “Why like, it’s gaily nigh like, to four mile like.”

Like emerged as a discourse marker centuries ago for the same reason that it has become so popular today: It is a surprisingly useful conversational tool.

Image Credit: Nicolás Ortega

TO SEE HOW LIKE COMES IN HANDY even in professional settings, take a sentence like, “I worked for, like, 80 hours.” The like that appears in this example might not seem as if it is serving any strictly necessary role. In fact, it could be deleted and the strict semantic sense of the sentence would remain (“I worked for 80 hours”). But you would lose some of what the speaker intends to convey, a certain linguistic je ne sais quoi. This use of like suggests the speaker is not completely certain of how long they worked (or doesn’t really care to be more specific) but is emphasizing the fact that the work period was impressively long.

Related: The 4 Most Important Words in Leadership Development

We will often state things strongly or weakly in order to persuade a listener about a position we present, or to resist making a strong claim, or even to share useful but potentially not exact information. In our example, “I worked for, like, 80 hours,” the speaker’s intent is to persuade the listener that the work was long and grueling, but probably not that it actually lasted 80 hours. In fact, if taken literally, one might not have much interest in pursuing conversation with someone so obviously in need of alternate leisure-time pursuits.

While often characterized as empty or meaningless in terms of the semantic contribution, such markers can be an important component of what we consider informative discourse. Compare the sentence, “John was, like, 21, when he launched the company” with the roughly equivalent utterance, “John was 21 when he launched the company.” Should a listener know John, and also know that he actually started his company at 22, the conversational import (that he founded a startup at an early age) intended by the speaker may be missed because the listener is more concerned that the sentence violated what they know about John. In linguistics we call this the truth-conditional meaning of sentences. Sarcasm and humor aside, speakers and listeners tend to aim for credibility. Thus, there is a subtle difference added by the use of like that may help a speaker make a point about John launching his company without getting sidelined by information regarding his age that could mess with our truth conditions. One could easily have said, “John was about 21 when he launched the company,” but that comes across as more reserved than carefree and hip.

Related: 5 Tips to Feel More Confident With Public Speaking

Just think about it this way: We hedge and qualify all the time in business. Along with the perfectly acceptable terms “think,” “may,” “possibly,” or “maybe,” like is just another way of expressing degrees of certainty.

Image Credit: Nicolás Ortega

HERE’S ANOTHER WAY that like adds nuance.

My daughter (a model like user) and I were recently talking about a party she attended. When describing a fellow attendee, she said, “She’s, like, one of the popular girls,” and then proceeded to tell me about this tween Amazonian’s death-defying acts of coolness. Now, I am doubtful that my daughter was trying to be vague about the girl’s popularity. Instead, by introducing the noun phrase “one of the popular girls” with like, she was highlighting the point she was trying to make. In other words, she was using like as a linguistic focuser. This function alerts the listener to a speaker’s emphasis or subjective take on a particular aspect of the sentence.

The problem for some is that when like is used in this way, it can seem to show up anywhere. But there is a method to the madness. One study looked at how discourse marker functions of like were deployed by speakers when retelling stories. It discovered that both the original speaker and the listener tended to recycle likes at the same points in the story when retelling it, suggesting that those specific likes really did matter in qualifying or supplementing the meaning. Like it or not (pun absolutely intended), like usage seems to be intentional and essential.

And now the plot thickens. While the above examples demonstrate the power of like as a discourse marker, the usage that seems to really rally the grammar prescriptivists is like as a quotative verb. As in, “I was like, ‘I can’t stand it!’ and she was like, ‘I know! I don’t like it either.'” This form of nonstandard like use seems to be the one people find most difficult to digest, which is unfortunate, because it’s also the most rapidly expanding one in English.

Related: 14 Proven Ways to Improve Your Communication Skills

In contrast to the long history of discourse-marker like, such quotative like use is a fairly recent development, with the OED first noting its appearance in a Time magazine article from 1970, where it was used to report internal dialogue of the speaker: “And I thought like wow, this is for me.” According to like experts, this reference is a throwback to the “Like, wow” phenomenon associated with beatniks in the 1950s and beat/jazz culture in New York City in the 1960s.

The popularity of quotative like use was mainstreamed by the song “Valley Girl” by Frank Zappa, with help from his daughter Moon Unit, in 1982. This song took popular culture by storm, drawing a caricature of the speech style used by girls from Southern California. Along with introducing the iconic phrase, “Gag me with a spoon,” it acquainted many of us with like in both its discourse-marker and quotative functions, helping to accelerate its spread. Still, the song simply reflected, rather than started, an undercurrent already in play well before it came on the scene.

When looking at how this be-like form is most often used, Canadian researchers Sali Tagliamonte and Alexandra D’Arcy find that it occurs most often with first-person narration of inner dialogue (e.g., “I was like” or “We were like”). Their findings echo research from the early 1990s that discovered speakers alternating between say and like to take on different narrating roles — using “they said” when directly reporting someone else’s speech but “I was like” mainly when characterizing their own thoughts or feelings. This suggests that be like is used primarily to help us convey different perspectives while describing a story or an event, perhaps to heighten dramatic tension.

Intriguingly, this rapid uptake and selective replacement of the verb “to say” appears to correspond with a fundamental shift in our narrative style during the latter half of the 20th century. Prior to the rise of be like, our stories were primarily intended as retellings of events. Now, however, we are also interested in narrating our thoughts as if spoken out loud during the moments we are describing. As a result, the focus has moved from strict reportage of the events themselves to our processing of these events. The verb “to say” didn’t sufficiently capture the subjective sensibility this new approach required, which led to the rise of be like, serving to inject first-person reflections. Think of the difference between “Then I said, ‘Hello there!'” versus “Then I was like, ‘Helloooo there!'” To say comes across as a verbatim quote while be like communicates a “something along the lines of” sentiment, and in fact might be taken here to describe what I was thinking rather than anything I actually said. Gradually, these first-person uses of quotative like extended to use with all potential subjects, so that now she can be like, he can be like, and so can they.

Related: Remote-Communication Tips from 7 World Champions of Public Speaking

Not surprisingly, most studies have found a greater use of modern like by younger speakers. But research suggests that it’s increasing among older speakers too, and there’s little evidence that its spread will be halted. Like it or not, like is becoming the new norm.

What does this all mean for you? Whether it falls from the lips of those you work with or even your own, you won’t go wrong being among the first to recognize this new like‘s utility and purpose. It’s especially helpful if you want to connect to millennials and Gen Z, who will find you more appealing and approachable. So, leaders of all sorts should relax about censoring the likes out of their speech or the people they oversee. And for those who remain unconvinced, instead of dismissing it as simply something to eradicate, consider how like has traveled from the innovative edge to become an enormously pervasive and popular feature of speech today — a true linguistic entrepreneur if ever there was one.

What’s not to like about that?

→ From LIKE, LITERALLY, DUDE by Valerie Fridland, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Valerie Fridland.

This article is from Entrepreneur.com