In 2010, the figure skating coach Frank Carroll, who has coached Asian American Olympians such as Michelle Kwan and Mirai Nagasu, said that skaters of Asian descent had found success on the ice because their bodies are “often small and willowy.”

“They have bodies that are quick and light; they’re able to do things very fast,” Carroll told The New York Times. “It’s like Chinese divers. If you look at those bodies, there’s nothing there. They’re just like nymphs.”

Carroll’s remarks were part of decades of Olympics commentary that zeroes in on Asian bodies, often focusing on athletes’ size, beauty and fragility. Experts say this type of generalization is racist and dehumanizing and part of a longer history of exotifying and sexualizing Asian women in the U.S.

Rachael Joo, an associate professor of American studies at Middlebury College and the author of “Transnational Sport: Gender, Media and Global Korea” told NBC Asian America that the representation of Asian American athletes hasn’t changed much over the years. “There’s a lot of misguided essentialism that’s going on,” she said. “If we’re going to talk about bodies, let’s not generalize by race or nation.”

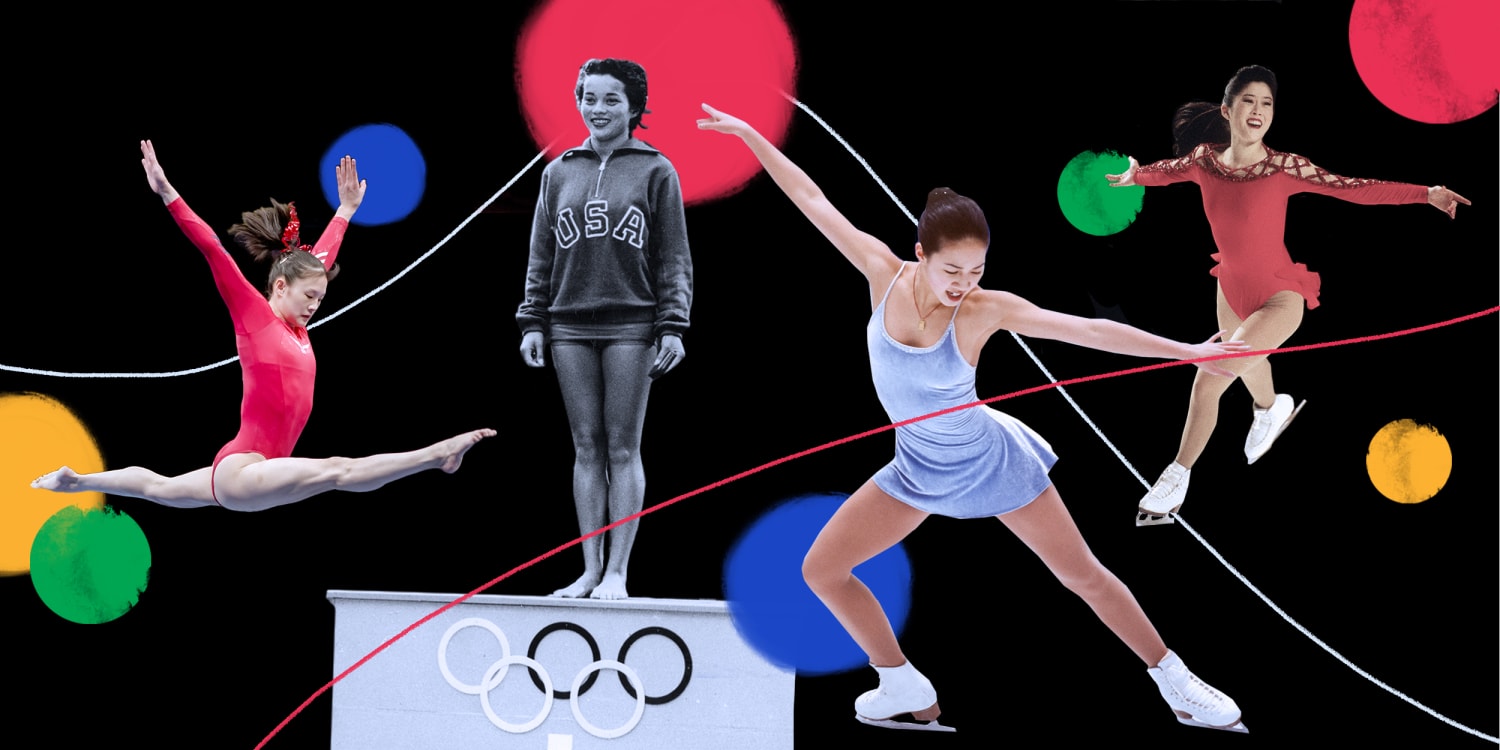

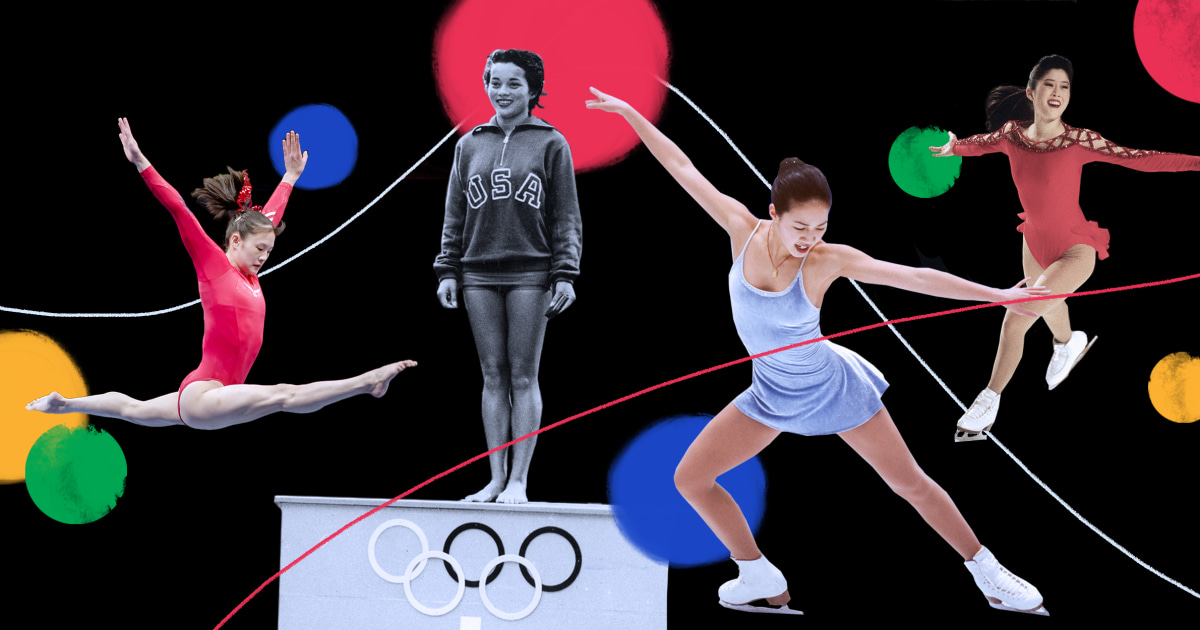

Asian Americans first made an impact in Olympic sports when Victoria Manalo Draves, who was called the Olympics’ “prettiest champion” by Life magazine, won a gold medal in platform and springboard diving at the 1948 games, becoming the first Asian American to earn gold. “Had there been a beauty contest at last year’s Olympic Games, the raven-haired girl shown here would have won it just as she won both of the women’s diving championships,” Life said.

Two days after Draves’ wins, Sammy Lee became the first Asian American man to earn an Olympic gold medal, winning in platform diving; he repeated in 1952. The San Francisco Examiner referred to the legendary athlete and U.S. Army medic as “Little Sammy,” calling him “pint sized” and “tiny.”

Decades later, descriptions of Asian American athletes remained much the same.

At the 1984 Winter Olympics, 16-year-old skater Tiffany Chin was nicknamed “China Doll” by journalists covering the games. In 1992, a Los Angeles Times article described Olympic champion figure skater Kristi Yamaguchi as “itsy-bitsy” and “fragile.” Reporter Mike Downey wrote that Yamaguchi was “not much bigger than a Barbie doll” when she began doing foot-long leaps on the ice as a child.

Newsweek juxtaposed “delicate” Yamaguchi with her competitor, “the stout little” Midori Ito of Japan, whose “powerful legs bowed in an old-fashioned way, what the Japanese once called, unkindly of their women, daikon legs, after the archipelago’s big, squat radishes.”

Experts say that when the media focuses on Asian American Olympians’ bodies, it erases the existence and excellence of their athleticism and makes it seem like their talent is simply innate and not the result of years of training and dedication. Critics also point out that Asians, like all ethnicities, have varied body types and there is no uniform way to describe them.

“This is one of the critical ways racism works — by creating these different terms of humanness and ability,” said Stanley Thangaraj, an anthropologist and the author of “Desi Hoop Dreams: Pickup Basketball and the Making of Asian American Masculinity,” who is also a former athlete and coach. “The talk of bodies flattens the differences within these communities and it essentializes them and creates a monolith of the community.”

In 1996, Carroll, the skating coach, told The Edmonton Journal that “Asian women have very little chests, very little boobs, and usually small bodies and tight hips. That’s ideal for figure skating because the weight distribution and the balance in the air, the axis, is very easy with that kind of body.”

During Kwan’s first Olympic Games, in 1998, Washington Post writer Amy Shipley said the then-18-year-old skater “looks delicate and graceful enough to put on the top of a Christmas tree.”

In The Cincinnati Enquirer in 2004, Paul Daugherty wrote that when 25-year-old American gymnast Mohini Bhardwaj spoke, she sounded “small, chirpy, 8 years old. As if someone stuck helium implants in her voice box.”

“Creating them as fragile plays into a larger racial rhetoric that constructs Asian Americans as not fully adults,” Thangaraj said. “We haven’t quite achieved adulthood and thus are seen as outside the realm of sport and the adult sporting American body.”

Broadcast media has echoed many of the same stereotypes seen in print over the years.

In 2010, NBC News’ Ian Williams was reporting on South Korean figure skater Yuna Kim when he said that “Asian skaters, particularly from Japan and now Korea, have the edge, their smaller frames enabling them to spin faster and jump higher.”

NPR published an infographic in 2012 about how Olympic bodies have changed over the years. It said that the ideal swimmer’s physique includes short, powerful legs, a huge wingspan, large hands and feet, and a long, tapered torso.

“Asians have the longest torsos relative to their body size, but they tend to be shorter, so swimming has long been dominated by Europeans,” reads a blurb next to a photo of five-time Olympic gold-medalist Nathan Adrian, who is 6-foot-6 and whose mother is Chinese.

Coverage of the Olympics is routinely criticized for being racist and sexist, and athletes like Chloe Kim have spoken out in recent months about being the target of racist abuse from sports fans.

As Asian American athletes prepare to compete in the Tokyo Olympics — including Sunisa Lee, who will be the first Hmong American Olympic gymnast; swimmer Torri Huske’; USA Karate’s Sakura Kokumai; and artistic gymnast Yul Moldauer — many Olympic watchers are hoping reporters will avoid cringeworthy clichés and racist stereotypes.

“There’s always going to be discussion of bodies, but I think the problem is when there aren’t female athletes doing the commentary,” Joo said. “I’m not saying it’s going to solve all kinds of racist or sexualized descriptions of people, but I do think that would be one important step.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com