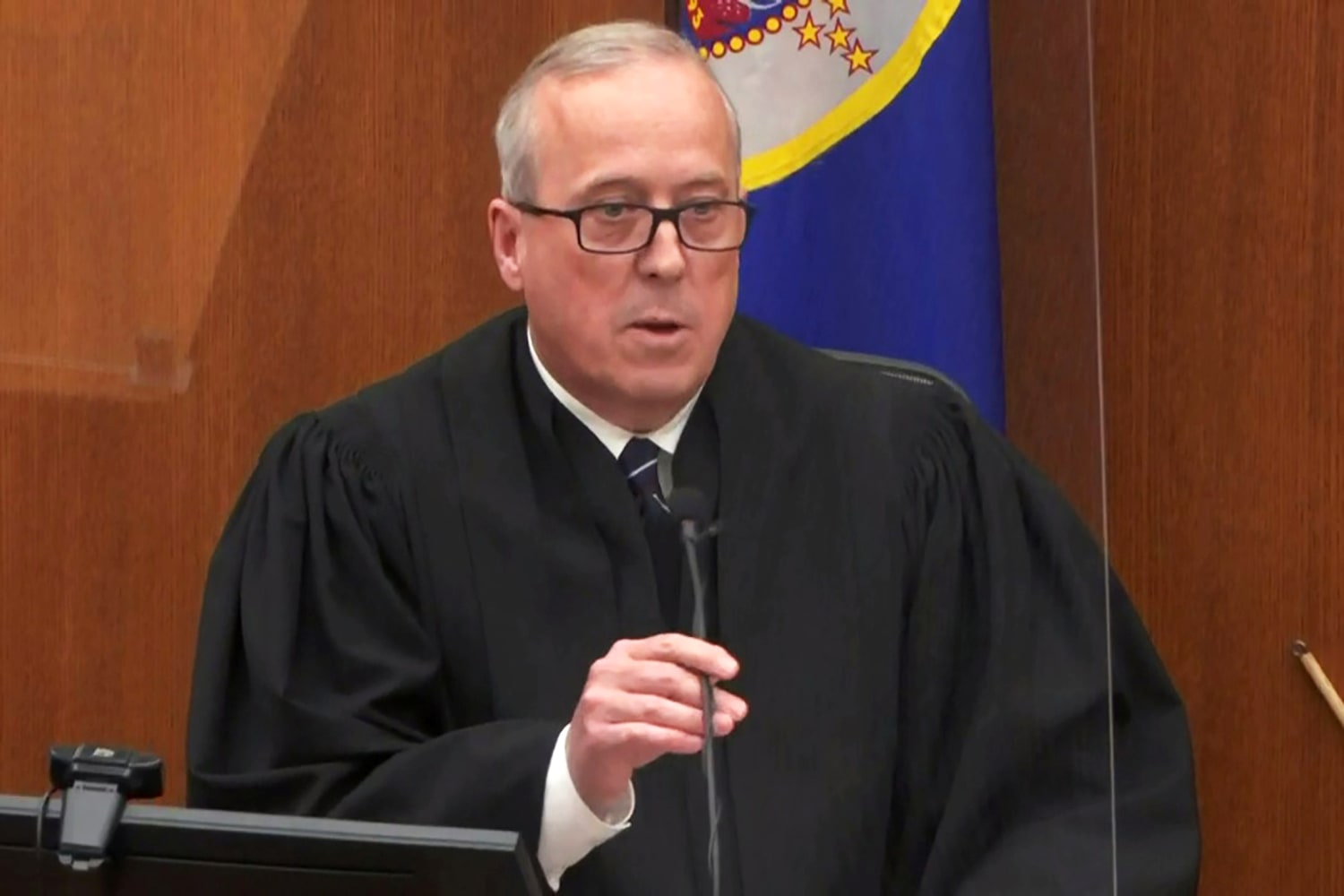

A Minnesota judge who, former colleagues and friends say, has no penchant for publicity will again find himself in the media spotlight this week when he sentences the former Minneapolis police officer convicted of murder in the death of George Floyd.

Judge Peter Cahill, who has served on the bench in Hennepin County for 14 years, could sentence Derek Chauvin to as little as probation, an outcome requested by his attorney, or more than the 30-year punishment favored by prosecutors.

In interviews, people who know Cahill and cases he has overseen say he is likely to land somewhere in the middle. They said he is a fair judge, though there is no guarantee he will mete out a punishment that will make either side entirely happy.

“He’s been both a prosecutor and a defense attorney,” said Craig Cascarano, 72, a Minneapolis lawyer in private practice who met Cahill at the Hennepin County Public Defender’s Office when Cahill was a law clerk. “So he understands what it’s like to do both jobs. And he tries very hard to do the right thing.”

Chauvin, who is white, was captured on a graphic video May 25, 2020, kneeling on Floyd’s neck for 9½ minutes, even after Floyd, who was Black, said he couldn’t breathe. Floyd’s death ignited a racial reckoning across the country and internationally. Chauvin and the three other former officers on the scene that day were indicted on federal charges of violating Floyd’s civil rights.

Cahill will sentence Chauvin on Friday, about two months after he oversaw the trial that ended in his conviction on charges of second- and third-degree murder, as well as second-degree manslaughter. Cahill has paved the way for Chauvin’s punishment to be up to double the 15 years at the top of the range recommended under state guidelines, having ruled in May that there were four aggravating factors in Floyd’s death.

In court documents filed this month, prosecutors asked that Cahill sentence Chauvin to 30 years. Chauvin’s attorney, Eric Nelson, requested a downward departure from sentencing guidelines or a sentence of probation with time served.

Mark Osler, a former federal prosecutor and a professor at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minnesota, said he believes that neither the defense nor the prosecution will get what they want.

“The defense request for probation is so far outside the guidelines and would be such a deviation from the way these cases are normally handled that I think it’s a zero percent chance that would be the outcome, regardless of who the judge was, frankly,” he said.

From 2008, the year he was elected to the bench, through January, Cahill has sentenced six people convicted of second-degree murder to prison. They received terms ranging from 12.5 years to 40 years.

In Cahill’s most recent case of sentencing on unintentional second-degree murder — the most serious charge on which Chauvin was convicted — he handed down a punishment of 15 years. In that case, Matthew Witt pleaded guilty in January 2020 to unintentional second-degree murder for beating his mother to death and to first-degree assault for violently attacking his father July 24, 2019, authorities said. He received an additional seven years for the latter charge.

In much of his other recent sentencing history, Cahill has deliberated on cases involving lesser charges than those on which Chauvin has been convicted. But he has had to make some higher-profile sentencing decisions.

In November 2019, he sentenced a man to seven years in prison for shooting at a school bus and wounding its driver during a snowstorm in Minneapolis. The man, Kenneth Lilly, pleaded guilty to one count of first-degree assault. Lilly said that he feared for his life after the slow-moving bus scraped his sedan, an argument Cahill did not buy.

Cahill sentenced Lilly to more than double the minimum three years that the defense had requested. Prosecutors had sought a sentence of eight years.

Michael Cohlich, a defense lawyer and friend of Cahill, said, “I certainly believe, and I don’t think anyone would argue with this, that he is not going to go below the guidelines.”

Having had cases before Cahill, “and just following some of the big cases he has done here in Minneapolis in Hennepin County,” Cohlich said, “I always remember thinking that fundamentally, that’s probably what I would have done, had I been sitting in his place.”

Cahill was picked by Chief Hennepin District Judge Toddrick Barnette to oversee Chauvin’s trial. Barnette declined through a court spokesman to comment on his decision to assign Cahill to the Chauvin case, referring NBC News instead to previous public statements.

“This moment is not too big for him,” Barnette told the Minneapolis Star-Tribune in March. “He will make thoughtful legal decisions based upon the law, even if the decisions are unpopular.”

Cahill, who declined a request for an interview, graduated from the University of Minnesota Law School in 1984. That same year, he began working at the county public defender’s office as an assistant public defender. He worked at Cohlich’s firm from 1987 to 1993.

Cohlich was already familiar with him. He said Cahill was the “go-to law clerk” when he worked at the county attorney’s office “as far as if you needed anything written or any research done.”

“And he also had a way about him with people, which is really significant for a trial lawyer and for a judge to be able to understand and respect people and at the same time to do your job,” he added.

After he left Cohlich’s firm, Cahill opened his own practice, which he ran until 1997 when he became an assistant prosecutor of violent crimes for the county attorney’s office. He spent 10 years in the county attorney’s office, seven of them as the chief deputy. He became a chief deputy under Amy Klobuchar, now the state’s senator, while she was the county attorney.

Those who know Cahill said his experience has proven beneficial as a judge.

Cascarano said he has tried cases against Cahill and before him with varying outcomes.

When asked to describe what Cahill is like as a judge, he said the first word that comes to mind is humble.

“He understands that a judge is there to kind of be the umpire,” Cascarano sad. “He’s going to call balls and strikes, so to speak.”

That much was evident, he said, during Chauvin’s trial.

“He was vigilant in making sure that this trial went forward in the fairest possible way,” he said.

Cascarano gave as an example Cahill’s decision to recall the seven jurors who had been seated before a $27 million settlement was announced between Minneapolis and Floyd’s family. The judge questioned the jurors about their ability to remain impartial after the announcement and dismissed two of them over concerns they could not. Neither the defense, which had asked Cahill to delay or move the trial or for the jurors to be recalled, nor the prosecution, which argued that the jurors did not need to be brought back in, got their way in that instance.

Like others who know Cahill, Cascarano said he is intelligent, meticulous and diligent.

In one of his more high profile actions, Cahill in November 2015 dismissed charges against the organizers of a massive Black Lives Matter rally that occurred in December 2014 at the Mall of America in Bloomington, which is privately owned and does not allow protests. In a 137-page decision, Cahill said he viewed many hours of the demonstration and described it as “peaceful.” He kept in place trespass charges against some participants.

Andrew Gordon, a lawyer who represented at least eight people who faced protest-related charges that arose from the rally, said Cahill “is nothing if not considered.” (At least two of his clients went to trial, one of whom was convicted, Gordon said.)

“He spends a great deal of time and effort thinking through his decisions and will sometimes go out of his way to over explain what he’s doing,” said Gordon, a deputy director at the Legal Rights Center, a nonprofit law firm in Minneapolis. “He’s a big communicator.”

He said Cahill has been fair in all of the cases he has tried before him.

“I think Judge Cahill is well aware that he isn’t just punishing Derek Chauvin, but he’s squarely in the middle of a larger conversation about whether the criminal court can be just in these types of cases,” Gordon said. “I don’t think anyone would be surprised if he follows the prosecution’s recommendation and sentences Chauvin to 360 months. I wouldn’t be.”

In 2019, Cahill sentenced figure skating coach Thomas Incantalupo, who pleaded guilty to one count of first-degree criminal sexual conduct and one count of third-degree criminal sexual conduct, to 24 years in prison — near the maximum sentence — for sexually abusing a figure skater when she was between 14 and 16 years old. The sentence was double the amount of time Incantalupo’s lawyers had requested and was three years less than the 27 years prosecutors had sought. At the sentencing, Cahill referenced a court document in which Incantalupo allegedly characterized the abuse as an “affair.”

“This is not cheating on your wife,” he told Incantalupo. “This is a crime against a child.”

Civil rights lawyer Brian Dunn, managing partner of the Cochran Firm’s Los Angeles office, said Cahill won him over with his handling of Chauvin’s trial.

“I was a bit skeptical at first given Judge Cahill’s refusal to allow prosecutors to reinstate the third-degree murder charge that was subsequently overruled by the Minnesota Court of Appeals,” he said. “However, I thought Judge Cahill remained fair and impartial throughout the trial and in making evidentiary rulings, especially given the international coverage and real-time scrutiny of each moment.”

Osler, the law professor, said Cahill displayed a lack of ego during the trial, which he said “is also an important part of his traditional persona.”

“What we saw in Judge Cahill was a recognition that he was not the person with the most at stake in that televised trial,” he said. “That he understood the gravity of the situation, the dignity of the victim and the stakes for the defendant.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com