“Some people complained of nausea and headaches,” Cutrer said of Livingston. The same has been true in East Palestine.

Wary residents in both towns turned to bottled water as officials scrambled to reduce the risk that hazardous materials would contaminate groundwater.

“They were very upset. They were having meetings all over the place,” Cutrer said of Livingston residents. “Air quality and water — that’s what the conversations were about. They were afraid to drink the water.”

Earlier this week in East Palestine, Gov. Mike DeWine and Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan drank the local tap water in public to assure residents it was safe.

That demonstration only proves the water is safe to drink today. Regular water monitoring, something implemented for decades in Livingston, will be needed, said Abinash Agrawal, a professor of environmental sciences at Wright State University in Ohio.

“We don’t know how much vinyl chloride seeped into the ground,” Agrawal said. “Once it gets into the ground, it will travel.”

Agrawal said it could take months or longer to create a detailed, three-dimensional map of where the toxic chemicals entered the ground and if and how they’re spreading at the East Palestine site. It’s possible that seeping chemicals could travel toward East Palestine’s public well sites, Agrawal said, adding that more data and field evidence are needed to evaluate that risk to drinking water. Cleaning a contaminated aquifer could take five to 10 years, Agrawal said.

Years of environmental testing and legal wrangling likely lie ahead. At least 14 lawsuits have been filed over the derailment impacts in the East Palestine area.

In the weeks after the Livingston derailment, local attorneys filed a class-action lawsuit against Illinois Central Gulf Railroad, according to Calvin Fayard Jr., an attorney who led the coalition.

The class action, which was settled in 1985, ultimately guided the cleanup and recovery process and reshaped the town. The $39 million settlement paid out more than 3,000 residents, created a commission to make decisions about the recovery and set aside funds to pay for long-term impacts.

The settlement provided funding for 30 years of regular water monitoring and established a fund to maintain a health clinic in Livingston, where residents could get a physical and blood testing each year for contaminants. The clinic remains standing.

Some damages were handled separately. A jury awarded nearly $3 million to Terry Wisner, a state police officer who responded to the derailment and later developed headaches, difficulty swallowing and shortness of breath. Wisner retired at age 38 due to his symptoms.

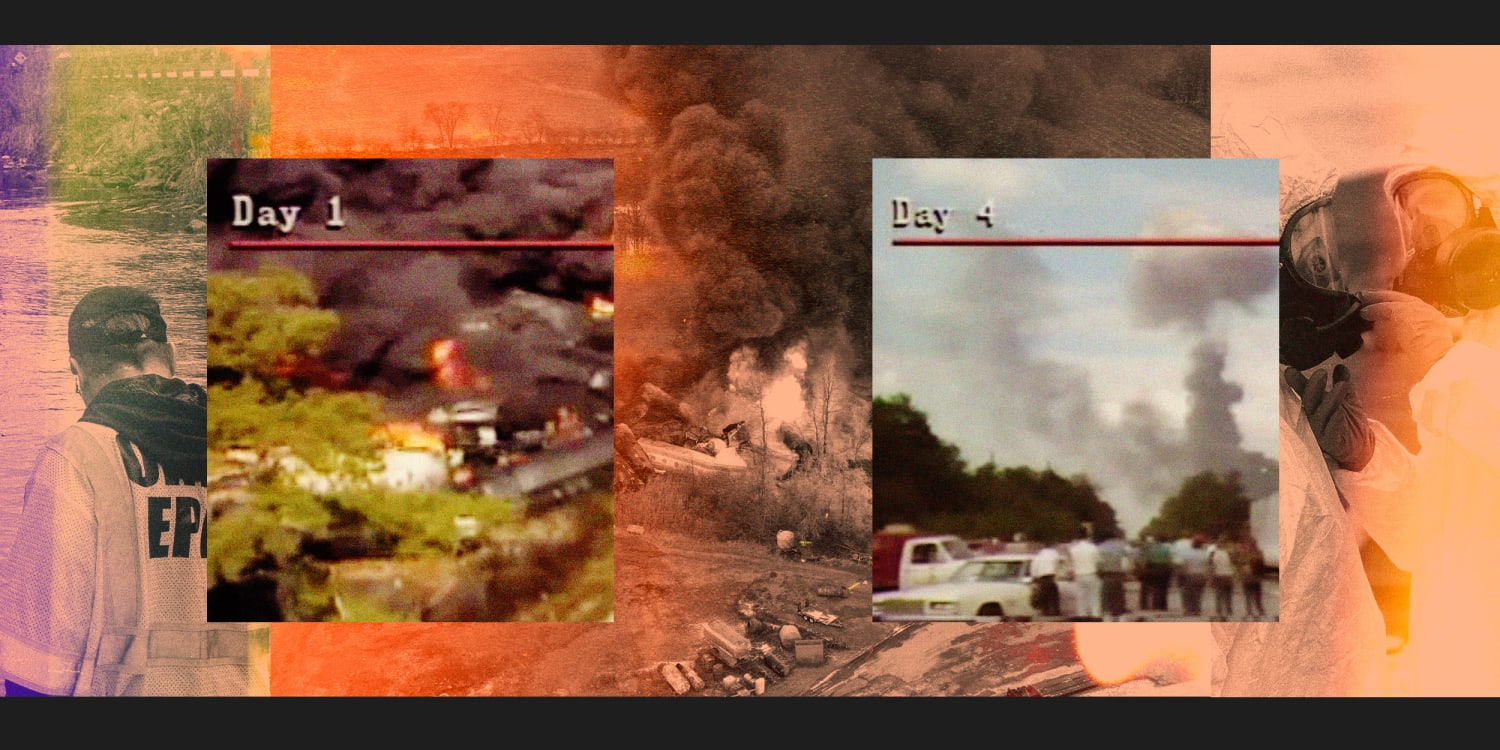

The town’s environmental recovery became a prolonged affair.

As part of the remediation, workers dug out affected soil to a depth of 50 feet and replaced it, Fayard said. They also pumped out contaminated water. Additional remediation efforts against perchloroethylene, a solvent used in dry cleaning, continued into the 2010s.

Aside from cases involving first responders, Bennett said he was not aware of lawsuits in which Livingston residents years later claimed that long-term health problems stemmed from chemical exposures. Testing never identified specific concerns, though many residents skipped visits to the clinic.

“Taking that annual free visit for toxic monitoring just was not on people’s high-priority list,” Bennett said. “In retrospect, it would have been an outstanding opportunity for a long-term clinical study.”

Contaminants did spread gradually in the soil and groundwater, but within acceptable limits.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com