In her two decades working in the Louisiana State University athletic department — a college athletics powerhouse — Sharon Lewis considered protecting the female workers and students a crucial part of her job. She said she was diligent about reporting racial and sexual offenses to her superiors — “several,” she said, filed over a span of 15 years.

That is, until her superiors denied getting a single one of them, she said.

“I couldn’t believe it. It was just all so overwhelming,” Lewis said. “I fainted.”

Lewis’ allegation is part of her $50 million Title IX lawsuit against the school, the board of supervisors, specific staff members and attorneys at the firm Taylor Porter, all of whom she alleges conspired in “unlawful discrimination with malice or with reckless indifference to federally protected rights to which she is entitled.”

She has a motion hearing next week in Louisiana to defend against the school’s efforts to have her case dismissed. Her comments to NBC News are her first extensive interview about her filing against one of the largest college athletics programs in the U.S.

While her work recruiting top athletes to come to LSU was integral to her job as the associate athletic director of football recruiting and alumni relations, she said that “protecting the school from itself became a part of what I had to do.”

So she said she felt betrayed when she realized her colleagues had “lied,” she said, to protect the university, which also meant they were sacrificing her to do so.

Lewis said she sent her own complaints and those from student workers in the football department, as well as her colleagues, to her superiors, Verge Ausberry, executive deputy athletic director, and Miriam Segar, senior associate athletic director.

But suddenly, according to the lawsuit, other administrators at the school claimed she had done no such thing.

“I learned after the release of the Husch Blackwell Report in 2021 and Taylor Porter law firm documents that they were out to get me and that I was being set up,” Lewis told NBC News about her tumultuous time at her alma mater.

Her professional career at LSU ended Feb. 5 when she was fired during what the school called “a vast restructure.”

She claims in her lawsuit that she endured years of discrimination and mistreatment — lack of equal compensation, sexual improprieties and harassment — stemming from being a Black woman who served as a whistleblower of bad behavior. Lewis also contends she was fired without cause and seeks damages.

For its part, LSU has denied her allegations.

“Regarding Ms. Lewis’ lawsuit, we intend to defend these claims vigorously and not let it distract us from our true goals of improving our university,” LSU Media Relations Director Ernie Ballard III said in a statement, adding that he will speak for all school employees.

One of Lewis’ attorneys, Larry English, has asserted claims under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, in federal court against school officials. RICO cases are usually associated with organized crime, and have never before been seen in an NCAA case. Lewis has brought similar claims in state court under the Louisiana Racketeering Act. While some of the RICO defendants were dismissed in federal court last year, English said he will continue to argue that “a criminal enterprise was running LSU’s athletic department.”

Recently, the NCAA filed a Notice of Allegations against LSU that said from 2012 to 2020 the school lacked institutional control over its basketball and football programs — the same time frame in which Lewis alleges she reported several sexual harassment complaints that were not investigated by the school. An institution has 90 days to address the NOA findings.

In the fallout, men’s basketball coach Will Wade was fired. The NOA alleged NCAA violations of a booster paying a football player’s family members $180,000 for working at a handful of events and NFL star Odell Beckham Jr. giving players cash on the field after they won the 2019 national championship. The report classified these violations as less serious in nature, but part of the larger “lack of institutional control” allegations in the case.

Meanwhile, an independent report by law firm Husch Blackwell in 2021 outlined myriad issues, including that the school failed to act on misconduct cases that had been reported. The report also said Lewis was the only staff member punished for not issuing reports, which it described as “ironic because Lewis has lodged several reports of sex harassment throughout her tenure.” Additionally, the investigation found that Taylor Porter, which had represented LSU for 80 years, did not report its findings from a previous investigation into allegations of sexual misconduct by then-football coach Les Miles to all of the school’s board members. LSU fired the firm, which did not respond to a request for comment.

Lewis, a former track athlete for the Tigers, was hired in 2002 and had served 20 years in the football department as an employee recognized for being an integral part of helping lure some of the top talent in the country to LSU. She was also elected president of the National L Club — a powerful alumni organization for former athletes and others associated with sports — where she remains in her role.

The university has become a springboard for many professional athletes and Olympians, but its football program is a crown jewel, with four national championships and dozens of former players filling out the rosters of NFL teams.

Lewis said she came forward with inappropriate conduct allegations against Miles in 2005 after their first meeting, during which he told her he “prefers blondes over brunettes.” Lewis’ lawsuit says she was “concerned Miles had an inappropriate fixation on female student workers.”

She reported her concerns to Ausberry and Segar, neither of whom “took action,” she said. Ausberry and Segar are cited as defendants in the lawsuit and declined to comment on it, citing an ongoing legal case.

Miles was directed to avoid interacting with student workers in 2013 — which, according to Lewis’ lawsuit, happened because administrators were aware of her reports — and he was eventually fired three years later. In 2018 he went on to coach at the University of Kansas, where he was placed on administrative leave and then left the university in 2021 amid revelations of the sexual misconduct allegations stemming from LSU. Miles’ attorney did not return a request for comment, but has in the past denied the claims.

Lewis insists in her lawsuit that she reported several other cases of inappropriate behavior by coaches and players to Ausberry and Segar. In the suit, she alleges that her bosses created a hostile work environment, where she was “subjected to discreet discriminatory acts and has experienced racially hostile work environment throughout her employment since 2005.”

LSU initiated the Husch Blackwell investigation after former Tiger running back Derrius Guice was arrested on domestic violence charges in 2020. The report found that the school failed to properly handle multiple reports of sexual misconduct within LSU athletics. Segar and Ausberry were briefly suspended by the university for their inaction to reports of sexual misconduct throughout the athletics program, but returned to their jobs. Guice, who had been drafted by the NFL’s Washington Commanders, reached a settlement with the victim and the charges were dropped in June. The league suspended him for six weeks for violating the personal conduct policy. Washington released him, and he has not been signed by another team.

The investigation recommended 18 changes to the program, including proper staffing of the Title IX office, revamping the reporting system, improving record-keeping and targeted training for athletes, among others. LSU says it has completed 17 of the recommendations.

The heart of Lewis’ case is this: The Husch Blackwell investigation concluded that Lewis was the only LSU staff member who reported complaints, and Ausberry and Segar were reprimanded for not acting on them. However, LSU is insisting Lewis did not make any reports, despite briefly suspending her bosses because they did not act on the same complaints Husch Blackwell found had been reported by Lewis.

“I am anxious to see in court how they explain that,” Lewis said. “If I was the only one reporting, and the investigation found that someone reported to Verge and Miriam and that they didn’t do anything, what’s their argument?”

Lewis said she felt ostracized and dismissed by some administrators in Baton Rouge. Lewis also said she was informed by LSU’s general counsel, Winston DeCuir, that she could not accept an invitation to testify at a hearing for the Committee on Women and Children, a standing committee commissioned after the release of the Husch Blackwell report.

DeCuir blocked Ausberry, Segar and anyone else from LSU from testifying because, he said at a hearing last year, it would be inappropriate for the individuals to speak, given the status of LSU athletics administrator Sharon Lewis’ $50 million suit against the school, according to LSU’s student newspaper, The Reville. The employees called to testify are potential witnesses in the suit. DeCuir did not respond to a request for comment.

Several former white female LSU athletes testified at the hearing about a culture of sexual abuse on campus — including a tennis player who said she had been raped and beaten several times by her boyfriend, a football player, after she had him arrested and suffered broken ribs among other injuries.

“The women were called ‘victims,’ which they were,” Lewis said. “I feel so badly for them and what they went through. But when my name came up, the only Black woman, I was called an opportunist.”

When asked about current employees testifying at the hearing, DeCuir said: “When you do an investigation like we did, and you make it public, invariably lawyers and other folks are going to take advantage of it and try to file lawsuits.”

Because Lewis now no longer works for LSU, her attorney has contacted the committee requesting Lewis be allowed to testify under oath at the next committee hearing.

She also alleged in the lawsuit that she repeatedly reported Frank Wilson, who was the running backs coach and LSU’s recruiting coordinator from 2010 to 2015. The lawsuit alleges that Wilson “exposed himself” to her in her office in 2013 and to two other Black women. Wilson was rehired at LSU last year by new coach Brian Kelly after taking two jobs elsewhere — at the University of Texas at San Antonio and McNeese State.

“Everything Sharon is saying is the absolute truth, and it’s crazy how much pushback LSU is giving, knowing it all is true,” a former worker at LSU, a Black woman, told NBC News on the condition of anonymity. She said she wanted to move on with her life and career, and that identifying herself could jeopardize that. She described allegations against Wilson that are included in the lawsuit, saying “while I don’t want my name used, I want the truth to be known.”

She said Wilson “would make comments about what I had on or he would stand too close to me or right on top of me while I was at my computer. And then it progressed to: ‘Let’s go to dinner to discuss recruiting.’ I said, ‘Frank, where’s your wife? If she says it’s OK for us to have dinner together, then sure, I’ll go to dinner with you to discuss recruiting.’ I was calling his bluff.

“He said, ‘Why do you need to involve my wife?’ And that would back him off for a while. One day we were in a meeting with another staff member, and while I was sitting at a table, Frank comes around to the side of me, kisses me on the lips. It was real aggressive. I was like, ‘What are you doing?’

“And then I got up and just ran down the hallway into Sharon’s office and just started crying. She asked, ‘What happened? What did he do?’”

Lewis, the woman’s supervisor, told her not to work “directly with Frank at all,” the woman recalled. She said Lewis “told Frank, ‘Anything that she needs to do for you goes through me first. And any meetings that we have, I will be in the room with her.’ It was her way of protecting me. But Frank retaliated against me, tried to get me fired. But Sharon wouldn’t have it.”

She said she did not report the incident herself, but Lewis said she reported it to Segar, according to the lawsuit.

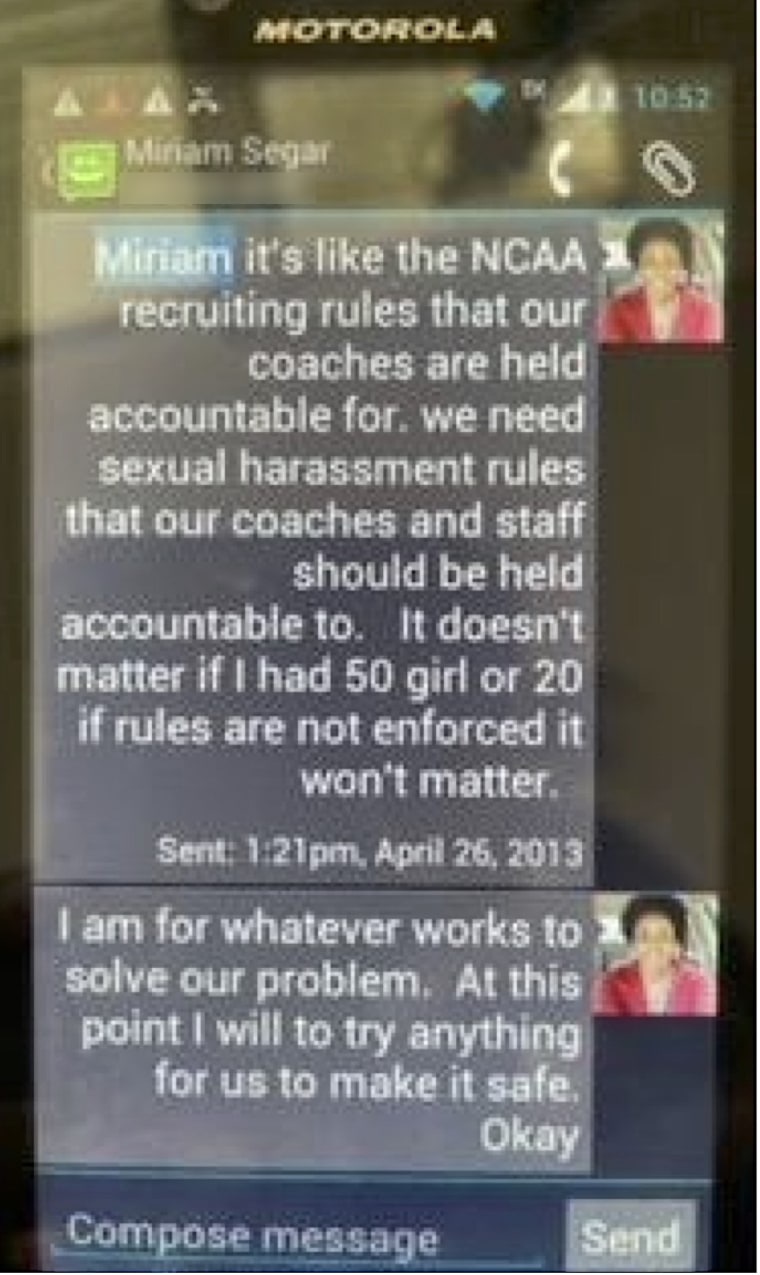

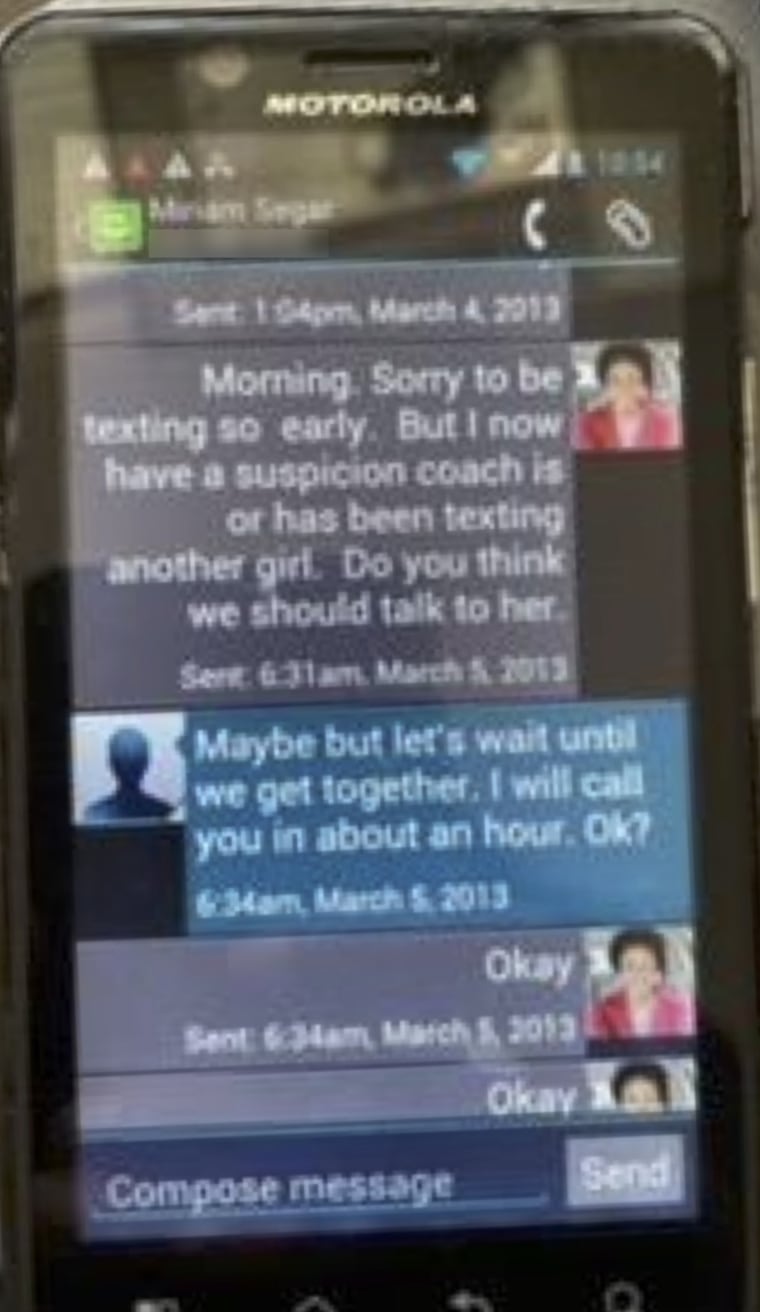

Lewis produced a screenshot of an April 26, 2013, text message to Segar that she said shows her concern about the culture in the athletic department. It read, in part: “We need sexual harrasment rules that our coaches and staff should be held accountable to. … I am for whatever works to solve our problem. At this point, I will try anything for us to make it safe.”

Lewis said she is not aware of any repercussions for Wilson.

“LSU has taken the position that these Black women’s voices don’t matter,” English, one of Lewis’ attorneys, said.

“This has been a nightmare,” Lewis said. “I did my job. I reported everything that came my way to the people I was supposed to report to. And this is how I’m treated for doing the right thing?”

Wilson and his family have deferred to a statement by LSU spokesperson Ballard, which stated: “There is no evidence that any allegations involving Frank Wilson were ever reported to LSU officials, and none of these allegations were shared during the highly visible, independent Title IX review by Husch Blackwell — a review process that Ms. Lewis participated in.”

As for Lewis’ firing, Ballard said, “While I cannot comment on a specific personnel action, I can provide that between reassignments and departures, there were 40 personnel changes in Athletics following the 2021-22 football season.”

Lewis said she has been going to therapy for years to manage the trauma of “working in a hostile place with no support. I don’t know why certain people are being protected by the board of supervisors. I have no idea,” she said. “But it is documented that they failed to do their jobs.”

According to the lawsuit, Lewis also said that before she lost her position, her emails and text messages to Ausberry and Segar on company devices about misconduct issues were erased. However, she said she found some messages that supported her claims on an old laptop and old cellphone and produced screenshots of messages to Segar pleading for help to “solve our problem.”

“No other emails were missing; just the ones from those two,” she said.

The defendants in the case are asking for the suits — both state and federal — to be dismissed, with a state motion hearing May 26.

“So, let’s get this straight,” Lewis said. “They are working on fixing the problems outlined in the Husch Blackwell report, which are the exact same things I reported were happening. And yet they are fighting me? For what? For telling the truth? But I’m glad they are cleaning it up; that’s what I want. But they also have ruined my life when all I did was my job. I just want for them to be held accountable for their actions.”

Follow NBCBLK on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com