This story about federal school funding was produced byThe Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

HILLSBORO, Ore. — Principal Christy Walters has big plans for her suburban elementary school. She wants to build on what she learned last year — better ways to stay in touch with families and help meet their needs, more effective strategies for recruiting and retaining a diverse staff, and new ideas on how to organize lessons to engage students.

“I’m always excited for innovation,” she said. “I’m not too tired for that. That is energizing.”

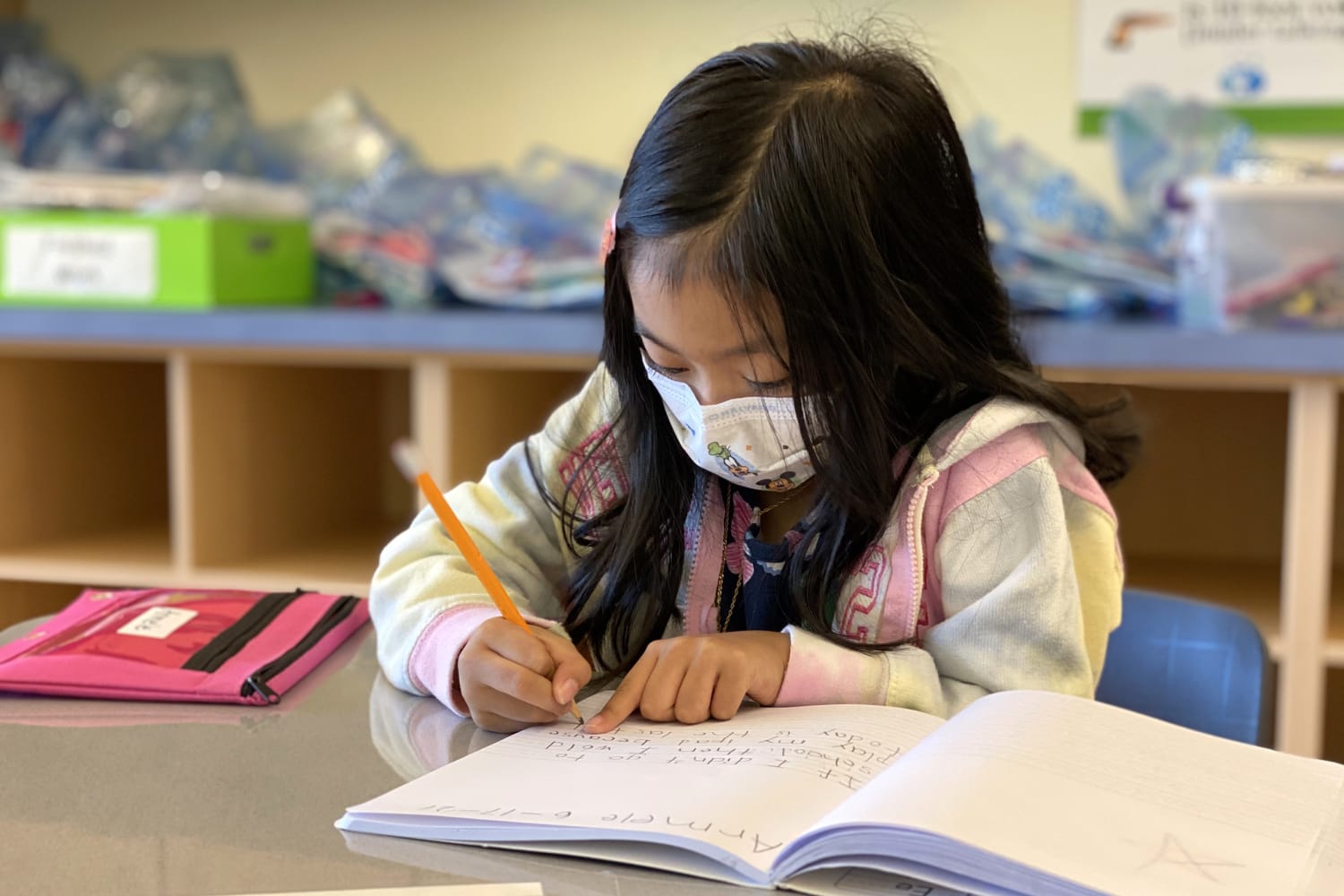

Witch Hazel Elementary, where Walters has been in charge since 2018, has a student poverty rate of 95 percent and an upbeat staff. Despite the immense challenges caused by the pandemic, adults here seem proud of how well they’ve survived a difficult year.

“It needs to be done, so we just do it,” said Alejandra Castrejon, the school secretary who helped Spanish-speaking families figure out how to use the Wi-Fi hot spots and tablets distributed by the district. “Everybody’s just been ready and willing to help.”

That spirit even impressed the nation’s top education official.

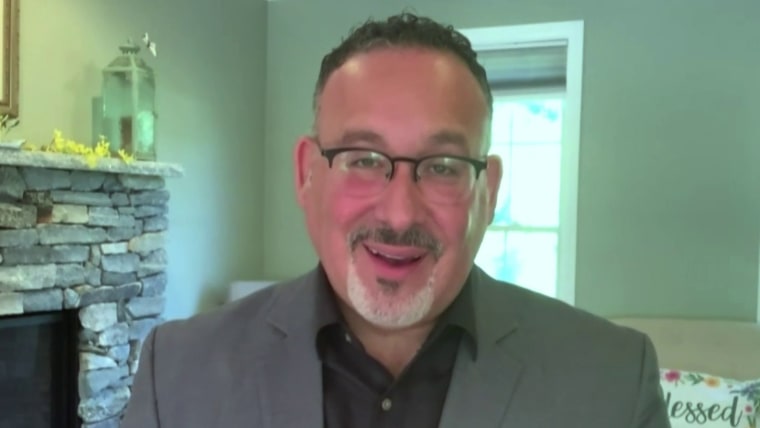

“I loved that school,” said Miguel Cardona, the U.S. Secretary of Education, a few weeks after a July visit to Witch Hazel to see its bilingual summer program. “People wanted to be there, from the students to the educators. I felt like kids were loved there. I felt like staff was supported there.”

He thinks this same kind of optimism can be found in many schools across the country, even as exhausted educators head into the 19th month of pandemic learning. His bet is that he can harness that energy and use it — along with an unprecedented level of federal cash — to finally fix what ails public education in the U.S.

Cardona is urging Congress to approve $103 billion in new discretionary budget authority for the Department of Education in the next fiscal year, a 41 percent increase over the current year’s budget. (That’s in addition to the no-strings-attached $122 billion in pandemic relief funding for K-12 schools that Congress approved in March as part of the American Rescue Plan Act.)

“We’re standing strong” with educators, Cardona said, “and want to come in stronger than ever before. Students have been waiting. It’s time to deliver.”

Should it be approved, the federal school funding he’s proposing could become a steady stream that’s nearly impossible to take back, meaning a huge change in federal control over local schools. Not everyone would welcome that change.

More money but at what cost?

Typically, the federal government has contributed only about 8 percent of the funds schools receive each year from local, state and federal governments. This proposal would increase the amounts available for public preschool, mental health counselors, special education services and teacher training, among other educator priorities.

“We’re talking about extraordinary increases,” said Rick Hess, the director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. “I’m an observer who has very little confidence that new dollars have historically been spent wisely or well.”

Hess does not believe federal school funding is being spent well now; more money would just exacerbate the problem.

“Most of these dollars are budgeted and allocated in a way which I generally don’t believe works in the interest of kids,” he said.

Conor Williams, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a left-leaning think tank, thinks sending more federal dollars to what he sees as a chronically underfunded system is a good plan, even if some of the money is spent unwisely.

“The kinds of money we’re talking about are so high that like, yes, it’s a good thing,” he said. “Thank God we’re doing it.”

By bringing the nation’s classrooms into tens of millions of homes, the pandemic offered the American public a close-up of the system’s failures: Education in the U.S. is inequitable, underfunded and too often ineffective.

And yet, it is also true that hundreds of thousands of hardworking teachers, principals and other school staff have been going to heroic lengths to help students who are struggling emotionally and academically.

That’s what’s happened at Witch Hazel, in the sprawling Portland suburb of Hillsboro. It’s a dual-language immersion school that keeps its students performing on a par with their low-income peers statewide. And Witch Hazel is not a complete anomaly. While many schools serving low-income students have poor academic outcomes, others serve their students reasonably well.

Walker said the strength of her school’s community, which can’t be measured by a multiple-choice test, is why it has survived the pandemic so far. For people to feel welcomed and supported, money alone is not enough — teamwork is the secret, she said.

“If we all want to do it together in concert, you know, then there’s nothing else really we need other than the people in the building, believing that that’s what we need,” she said.

Of course, those people need to be paid. And as positive as they are in general, several staffers said they wish they had smaller classes, a concern echoed by teachers districtwide according to the district’s chief financial officer, Michelle Morrison. But solving these issues is expensive, Morrison said.

“Reducing class size by one across the district is $2.7 million,” she said of her 20,000-student district.

Decades of research show reducing class size has a minimal effect on students’ academic progress. But smaller classes are more pleasant to lead and attend. With more funding available, local districts could invest in reducing class size or in any other preferred strategy that falls within the fairly broad categories outlined by the federal government in the Every Student Succeeds Act, which governs how federal money can be spent in K-12 schools.

Who decides how the money is spent?

Cardona’s faith that local leaders will make smart decisions about how to spend money most likely stems from his own past as a classroom teacher. He is one of just three former teachers to hold the education cabinet post since it was established in 1979. He said he sees his agency as “the connective tissue” between schools, ensuring that good ideas spread quickly and widely.

To make that happen, federal officials must ask locals how to spend any new federal school funding, said Kalilah Harris, a veteran of the Obama administration and the managing director for K-12 Education Policy at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank.

“They have the best information about what will work for their community,” Harris said of teachers, parents and other community members.

She also hopes the feds will help encourage district leaders to think big.

“Because so many districts were underresourced, people don’t even have ideas about what to use the money for that would be innovative and reimagine public education to work for their children,” she said. “You see some folks saying, ‘Oh, now we can have more of what we had before.’ But what we had before was not working for children either.”

What’s not working for children in Hillsboro, said Assistant Superintendent Travis Reiman, is the stop-and-start funding they’ve gotten for years from government at both the federal and state levels.

“Sustainable and adequate funding for K-12 is going to be key in the next decade and in the next 20 years,” Reiman said. He thinks sustained state money will be more helpful in the long run than the temporary relief the feds have sent so far, which can’t be put toward ongoing costs, like salaries.

Morrison, the district’s CFO, does not think the answer is more federal school funding. She thinks the feds should cover their own mandates and the state should act to keep funding equitable between wealthier districts and those with fewer resources. Beyond that, she thinks locals should pay for their own schools.

But the federal government is better at protecting civil rights than state or local governments, said the Century Foundation’s Williams. And the idea that local school boards are “bastions of democracy” is misplaced, he said.

“No, they’re not!” he said. “If you think that, you’ve never been to one.”

Though it’s not a widely held opinion in Washington, Williams said he thinks it might be better if the federal government simply ran the nation’s schools.

“It would be more in line with the rest of the developed world, and, I suspect, better for overall resource and outcome equity to have the feds, largely speaking, in control of American public education,” he said.

Will more federal dollars mean more federal control?

Meanwhile, Republicans have been far more likely to call for the elimination of the federal Department of Education than for its expansion. The idea was popularized by President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s and gained new traction during Donald Trump’s run for president in 2016. (The first Department of Education, established in 1867, was quickly demoted to an Office of Education “due to concern that the Department would exercise too much control over local schools,” according to a short history of the Department on its website.)

The U.S. Department of Education was created in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter. The following year, Reagan chose a former teacher, Terrell Bell, to come to Washington and dissolve the department.

When that proved impossible, Bell called for a study of the state of education in America. The result, published in 1983, was “A Nation at Risk,” a report that guided the next several decades of thinking about what was wrong with education in America and gave weight to the idea that federal efforts to improve education were warranted.

Federal school funding has waxed and waned over the last 40 years depending on who is in the White House. But thinkers on both the left and the right see Cardona’s move to dramatically increase funding as a potential step toward increased federal control of education.

“Let’s imagine, against all odds, that we come out of the crises we’re in and the money actually doesn’t go away right away, it gets sustained for a while,” Williams said. “And let’s say it’s like eight years down the road, 12 years down the road, when we’re in a more stable economic, public health and political moment, and a new administration announces, ‘Hey, actually, now that we’ve covered this huge amount of the bill, we are going to add some new conditions to that money.’”

By that point, he thinks local districts would be more reliant on the federal school funding and they’d be less likely to walk away from it no matter the conditions, he said.

While Hess, at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, called the increase “extraordinary,” he also argued that it isn’t enough to make a big difference.

“Pennies on the dollar,” he called it, pointing out that though the additional $30 billion Cardona is asking for would be a large increase in federal spending on education, it would be only a 4 percent increase over the $762 billion American taxpayers spend on public schools each year. Still, Hess granted that it might be enough to shift power over schools toward the federal government.

“You think Democrats might be concerned about what an aggressive … organized, kind of populist Republican administration might want to do with that now-supersized department,” he said.

Cardona is many years and several election cycles away from running a supersize department. As he pushes his new budget in a divided Congress, he hopes the Rescue Plan money will whet appetites for more federal investment.

“While I know not everyone voted for it, I know everyone’s districts are benefiting from it,” he said. “And I’m hoping that that can help both sides of the aisle see examples of how, when we invest in education, good things are possible.”

With a broad definition of “good things” and little oversight of local spending decisions, Cardona seems to be aiming, for now, for lots of federal funds and lots of local control.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com