Presidential inaugurations serve as the high holiday of our American civil religion: In front of “the temple of our democracy” — the Capitol — presidents and vice presidents take their “sacred oaths” by placing their hands upon special bibles, often with histories as rich as the ceremony itself. The president’s inaugural address serves as a kind of sermon or catechism to the masses, guiding us as to how a new president’s goals and aspirations reinforce our ideals and stem from events that have brought diverse Americans together across this country’s highly imperfect history.

“Civil religion,” then, is a scholarly term for the common understanding of principles, ideals, narratives, symbols and events that describe the American experience of democracy in light of higher truths. Or, if you don’t like the word “religion,” think of it as a civic creed, a public ethos or even the set of American values that define our sense of “who we are as a people.”

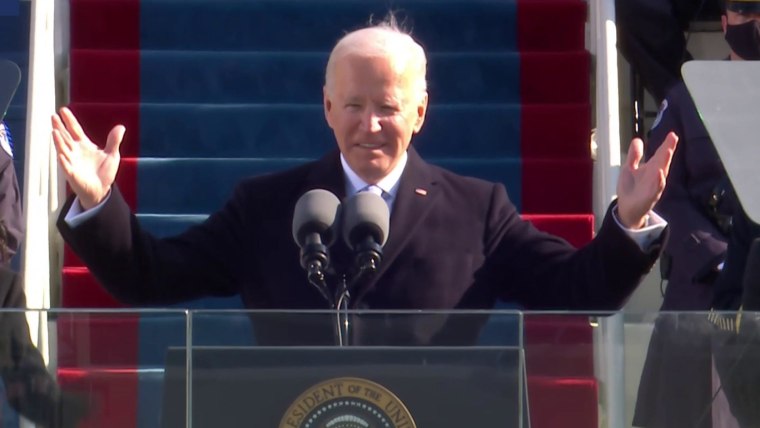

President Joe Biden’s inaugural address Wednesday was an embrace of our civil religion, offering a vision for confronting the “foes we face” and for redeeming the republic by extolling and expounding on the theme of unity. Unity is not, he said, some “foolish fantasy” — he isn’t calling for unity for its own sake or as way to allow others to dodge accountability or elide differences — but a moral and political necessity. Simply put, he explained, Americans cannot defeat the Covid-19 pandemic, rebuild our economy, confront racism, restore trust, heal our divisions and re-create a society committed to facts and truth unless we come together.

“For without unity,” he said, “there is no peace, only bitterness and fury, no progress, only exhausting outrage, no nation, only a state of chaos.” Put simply, without unity, we cannot remain the United States of America.

The toxic rhetoric, bitter divisions and deadly violence of the last four years have brought America to its knees and tarnished its standing in the world.

Biden’s call for unity — which he conceives by appealing to “history, faith and reason” — draws on the essential features of American civil religion.

He recalled, in part, the past trials our nation has faced — such as the Civil War, the Great Depression, world wars and 9/11 (which produced some of our most memorable inaugural addresses) — and summoned Americans to show grit and courage to confront the “crucible for the ages” in which we have found ourselves. Mixing hard truths with hopeful words, Biden reminds us that there is “much to repair, much to restore, much to heal, much to build and much to gain.”

Faith, too, has been a recurring element of past inaugurals, from appeals to the Almighty to thanksgivings for the blessings of liberty, as well as prayers to guide America in its special role in the world. Biden recalled such exceptionalism in his appeal not to lead by the “example of our power” but rather by “the power of our example.” And he became only the second president to cite St. Augustine (after President John F. Kennedy, the only previous Catholic president) and the first president to invoke Augustine in an inaugural address.

For Augustine, a people — a nation — is “a multitude defined by the common objects of their love.” No other president has asked Americans to look at themselves in this way: “What are the common objects we as Americans love, that define us as Americans?” asked Biden. “I think we know. Opportunity, security, liberty, dignity, respect, honor and yes, the truth.”

The previous administration, by comparison, showed us the horrors that befall a democracy that ignores truth or deliberately creates alternative facts and realty.

He isn’t calling for unity for its own sake or as way of allowing others to dodge accountability or elide differences, but as a moral and political necessity.

Finally, Biden offered that unity comes through reason — which harks back to the rational and republican roots of our democratic civil religion. Reason and argument, he said, trump violence and chaos. Biden made it clear that vigorous disagreement is fundamental to democracy and need not lead to disunion.

The toxic rhetoric, bitter divisions and deadly violence of the last four years have brought America to its knees and tarnished its standing in the world. Trump’s battering of civil religion and its replacement with a racist form of Christian nationalism, culminating in the Capitol insurrection, produced visible cracks in the moral foundations of our democracy.

But civil religion has long been a bipartisan language that any — well, almost any — president can speak. It helps to establish the guardrails of our republic and provides a framework within which citizens can disagree.

And it helps makes sense of the American experiment by placing historical events such as the Revolution, the Civil War, the world wars and the civil rights movement in the context of the higher truths that elucidate them. For Biden, we unite through such higher truths as dignity, decency, hope, healing and love. “May this be the story that guides us,” Biden said. “The story that inspires us and the story that tells ages yet to come that we answered the call of history.”

“We met the moment,” he added. “Democracy and hope, truth and justice did not die on our watch, but thrived.”

For four years, we have lacked a language to articulate the unity that many of us crave or a president whose rhetorical fluency could summon our higher angels, instill humility and encourage us to recommit to the covenantal principles of equality and dignity that hold Americans together. President Biden’s revival of civil religion after a four-year absence offers a clear alternative to the country as it confronts a pandemic, a recession, an insurrection, another impeachment, ongoing racism and a crisis of truth.

Leaning on civil religion’s language of a higher calling, justice and common purpose, Biden’s inaugural speech provided a moral framework within which diverse Americans can unite, reconcile and begin to redeem our troubled nation.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com