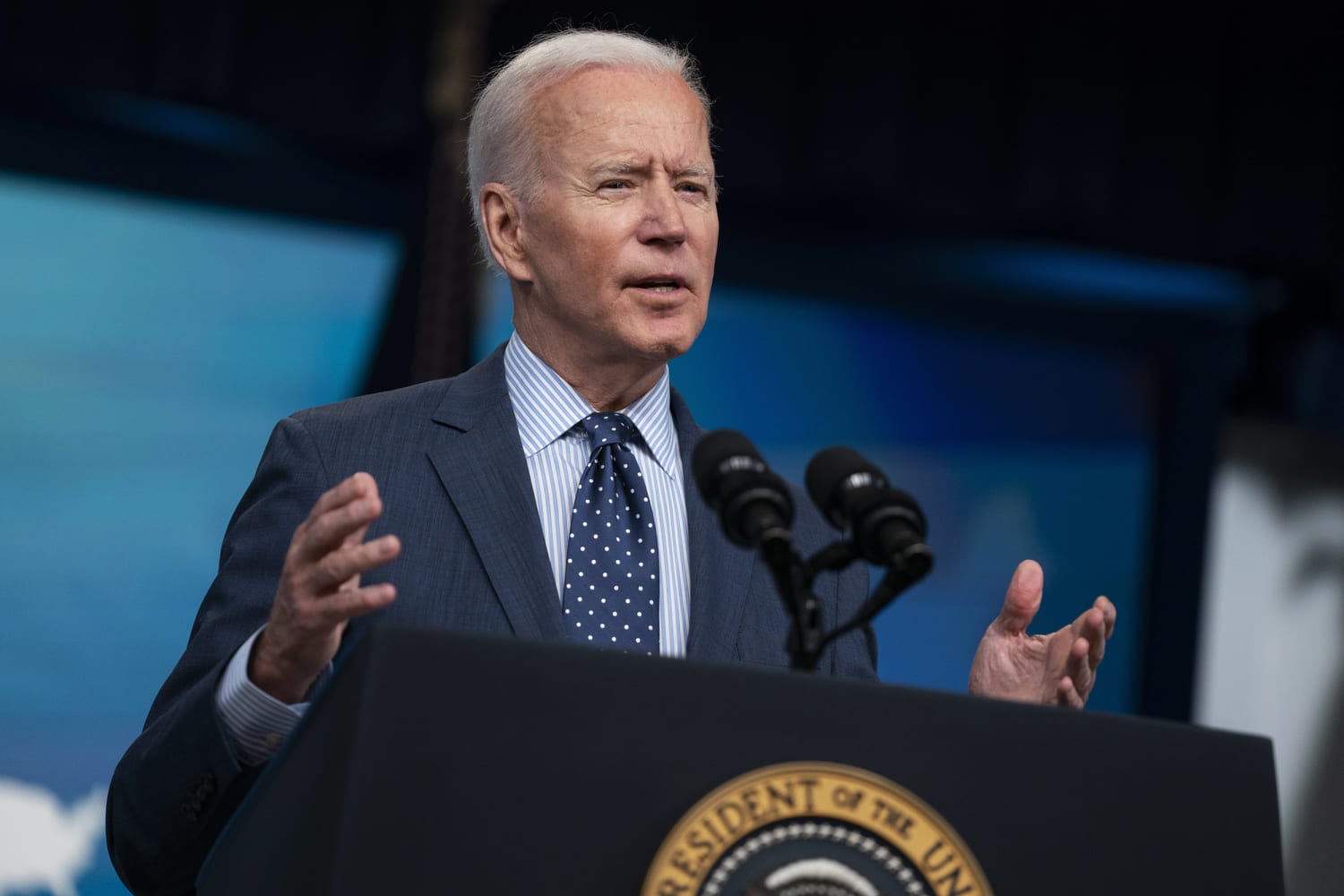

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden will touch down in Europe on Wednesday looking to repair relations with America’s closest allies in an effort to counter growing threats from China and Russia in his first big moment on the world stage since taking office.

In many ways, it will be familiar turf for Biden. Few presidents have had his level of foreign policy experience, from decades on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to his time as vice president. But the world has experienced dramatic changes in the more than four years since Biden was last on the front lines of American foreign policy.

The global economy has been upended by the Covid-19 pandemic; China has become an even more dominant economic and military power; and the growing capabilities of Russian-based actors to carry out cyberattacks have hit Americans at home. Amid all those challenges, America’s oldest allies are skeptical they have a partner they can trust after four years of the Trump administration’s “America First” foreign policy.

Senior administration officials fully acknowledge the challenges they face and are pragmatic in what they believe they can achieve as they head overseas. Biden has framed the trip as being more about the means than the ends — focusing on re-establishing America’s place at the international negotiating table rather than on how he hopes to achieve U.S. objectives with that seat.

“This trip is about realizing America’s renewed commitment to our allies and partners, and demonstrating the capacity of democracies to both meet the challenges and deter the threats of this new age,” Biden said in a Washington Post op-ed Saturday.

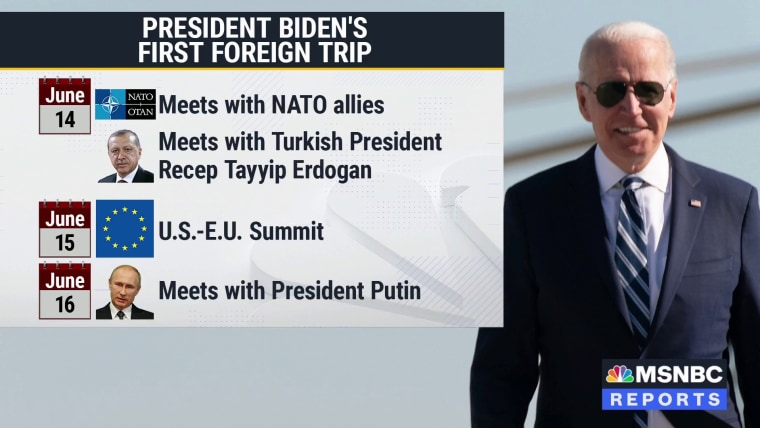

Biden will begin the trip meeting with U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, followed by a gathering of the Group of Seven leaders, which include the heads of state from Canada, the U.K., France, Italy, Germany and Japan. He will then attend a meeting of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and have an audience with Queen Elizabeth II before attending what administration officials have indicated will be a contentious meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Bridging the distance across the Atlantic

Biden is expected to get an overwhelmingly warm welcome from the allies, who for four years tried to manage then-President Donald Trump’s often undiplomatic diplomacy style, said national security officials from the Trump and Obama administrations.

At Trump’s first G-7 summit he sparred with his counterparts on climate change and trade. The following year, he left the summit early for a meeting with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un, lashing out at Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on Twitter on his way out the door. The last time Trump met the G-7 leaders in person, in 2019, he threatened a trade war with France and pushed for Putin to be included in the group.

“They were for the most part train wrecks and there was a lot of blood on the floor by the time Trump left these meetings,” said Charles Kupchan, who served as senior director for European affairs in the Obama administration and is currently a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, of the last G-7 summits. “So there is a massive sense of relief for the semblance of normalcy back in the White House.”

But Biden will face a skeptical audience from world leaders in trying to re-establish America’s leadership role amid concerns any international agreements they are able to reach with the U.S. over the next four years will only be undone by the next president, as the Paris climate agreement and Iran nuclear deal were upended by Trump.

“The allies do have lingering doubts about the forces that produced Trump’s election in 2016 and are wondering whether those forces are gone for good or the possibility that the U.S. could shift back to a more contentious, more transactional approach,” said Alexander Vershbow, former deputy secretary general of NATO and U.S. ambassador to Russia in the Bush administration.

One advantage Biden will have is his well-established relationships with a number of the leaders he will meet this week. The in-first person foreign gathering of his presidency will give him the opportunity to have informal conversations with his counterparts over dinner, drinks and walks, said Kupchan, who helped prepare Biden for a number of foreign trips when he was vice president.

Putin takes the spotlight

It isn’t by accident that Biden will spend nearly a week meeting with America’s closest allies before his summit in Geneva with Putin — national security adviser Jake Sullivan said the timing is intended so Biden can head into the Putin meeting “with the wind at his back.”

The list of contentious issues the White House says Biden will address with Putin is long and includes ransomware attacks, human rights violations, election interference and aggression toward Ukraine. Administration officials have said they anticipate the one-on-one meeting to be lengthy and tense, and they don’t expect any deliverables to come out of the meeting.

Sullivan said Biden will lay out what the U.S. expectations are from Russia and what America’s response will be if certain activities continue to occur. It’s a message he said Biden needs to deliver directly in person to Putin.

“Taking the measure of another president is not about trusting them, and the relationship between the U.S. and Russia is not about a relationship of trust,” Sullivan said. “It’s about a relationship of verification, it’s about a relationship of clarifying what our expectations are and laying out that if certain kinds of harmful activities continue to occur, there will be responses from the United States.”

Tackling the pandemic

While the Putin summit has put Russia in the spotlight, Biden and world leaders are expected to focus most of their attention behind closed doors on larger currents rippling through the world, including climate change, Covid-19 and China, administration officials said.

In the near term, Biden will have to confront a world still struggling with the Covid-19 pandemic from economic and public health perspectives. Central to getting the world back on track will be greatly expanding the supply of vaccines to lower- and middle-income countries, many of whom have vaccinated just a small fraction of their populations.

“Everything hangs on vaccine distribution, and the success and the durable recovery of G-7 nations, of developed countries, relies on the distribution to the developing world, where, of course, we derive much of our supply chains,” said Julia Friedlander, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and the White House director for the European Union, Southern Europe and economic affairs during the Trump administration.

The U.S. has committed to shipping 80 million doses of the Covid-19 vaccine overseas by the end of June, with 25 million set to be sent out in the coming weeks. But the commitment — while more than any other county — is a tiny fraction of the 1.8 billion doses international aid groups are aiming to get to lower-income countries by early 2022. The U.S. has been criticized by world leaders and public health officials for restricting U.S. companies until recently from shipping vaccine raw materials and supplies overseas and for stockpiling tens of millions of doses that weren’t being used.

Sullivan said Biden will outline wider plans during the trip for how the G-7 nations will respond to the pandemic, and administration officials have signaled that the current international vaccine commitment is only the start of what the United States plans to distribute.

Us, not them

Beyond the pandemic, Biden and the world leaders are also expected to discuss steps they can take together to address climate change and the growing proliferation of cyberattacks. They also plan to discuss ways to counter China’s rising influence “so that democracies and not anyone else, not China or other autocracies, are writing the rules for trade and technology for the 21st century,” Sullivan said.

But much as the G-7 and NATO leaders will be focused on addressing issues and challenges beyond their borders, like the global pandemic, Russia and China, there is also expected to be increased focus on the domestic challenges they will each have to confront.

“One thing new about this meeting is that the conversation has to be more about ‘us’ than about ‘them,’” Kupchan said. “The elephant in the room is the political turbulence and dysfunction that has fallen in the West. We have just lived through a shocking era in American politics, Britain has just left the E.U., populism is alive and well across Europe. Part of the conversation has to be about us and what we can do to make sure liberal democracy is rock solid.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com