A string of back-to-back deaths of Indian students at colleges across the country has left the South Asian community shaken, sparking anxiety in peers and parents.

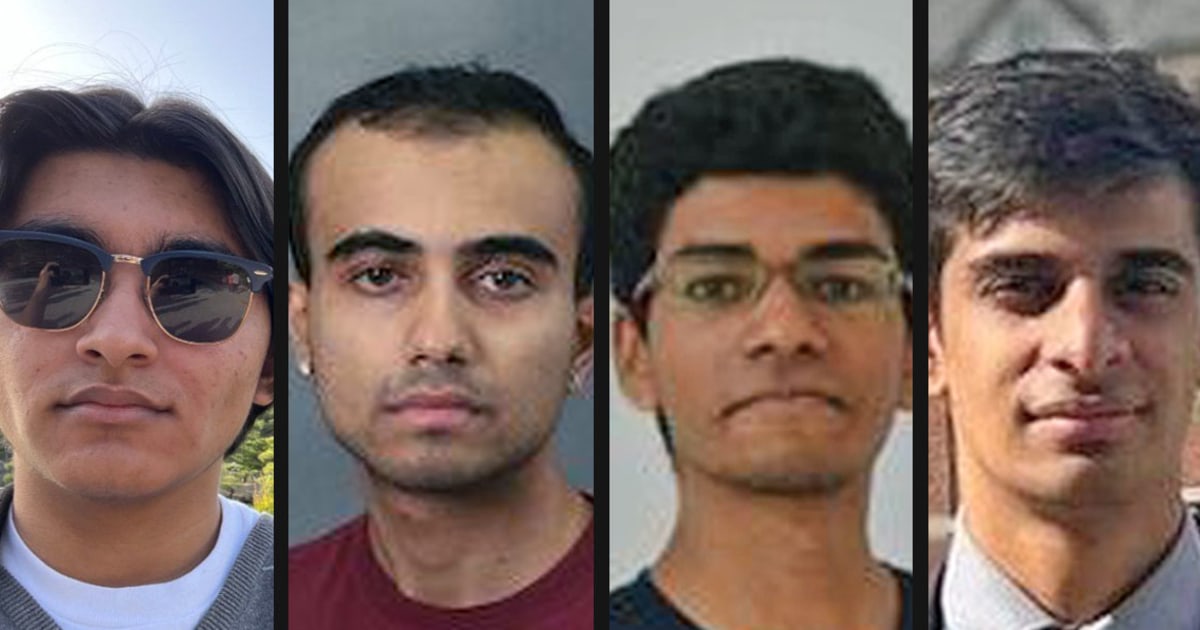

In 2024 alone, seven students of both Indian and Indian American origin have died. All men 25 years old and under, two committed suicide, two died of overdoses, two were found dead after going missing, and one was beaten to death, according to police records in states ranging from Connecticut to Indiana.

In Indian communities both in the U.S. and abroad, many are looking for answers.

“It felt like a pattern, like, why was it another Indian kid?” said Virag Shah, 21, a junior at Purdue University in Indiana, where two of the seven deaths occurred. “It just felt traumatic.”

Shah is the president of the school’s Indian Students Association, and he says his peers are alarmed by the repeated incidents.

On Jan. 28, the body of 19-year-old Neel Acharya was recovered on Purdue’s campus. Acharya had gone missing after a night out, Shah said, and was found dead the next morning. Coroners say a cause of death still hasn’t been determined, but there was no trauma to the body.

Just over a week later, Purdue graduate student Sameer Kamath, 23, was found deceased in the nearby woods with a gunshot wound to the head. Medical examiners say he died of suicide on Feb. 5.

These two deaths followed a high-profile case at Purdue in October 2022, when Varun Manish Chheda, 20, was brutally stabbed to death by his roommate, according to police. In December 2023, his alleged killer, Ji Min Sha, was deemed incompetent to stand trial, local news outlets reported.

A Purdue spokesperson directed further questions to the county coroner.

To experts, the number of fatal incidents involving Indian men in the first few weeks of the year is cause for concern. Deaths have been mounting since Jan. 15, when the bodies of two Indian-origin students at Sacred Hearts University, were discovered in their Hartford, Connecticut residence, authorities said.

Dinesh Gattu, 22, and Sai Rakoti, 21, both suffered from accidental overdoses involving fentanyl, according to the Connecticut Chief Medical Examiner.

A day later, on Jan. 16, 25-year-old Indian graduate student Vivek Saini was allegedly beaten to death in the store where he worked in Lithonia, Georgia. The Indian Consulate tweeted saying it was involved in the case and working to repatriate the body to India.

“It doesn’t take a lot when these gruesome things happen,” said Pawan Dhingra, a professor of American studies at Amherst College. “People will be like, ‘Oh, my gosh, this could have happened to my child, this could have happened to me. Is this really the place I need to go for my higher education?’”

Four days after Saini’s death, the body of Indian American freshman Akul Dhawan, 18, was found in subzero temperatures on University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign campus. He was reported missing by a friend after leaving their dorm at around 1:30 a.m., and though campus police said they did an extensive search, his body was found 10 hours later by a passerby, just 500 feet away from where he was last seen.

“It is so unimaginable that a kid can die in this day and age right on the university campus,” his father, Ish Dhawan, said.

At the University of Cincinnati, Shreyas Reddy Beniger, a 19-year-old student of Indian origin, was found dead on Feb. 1 from an apparent suicide, local police said.

“It’s just tragic,” Dhingra said. “People in India, you’re seeing these stories, multiple stories. You start to wonder, is this still the right pathway?”

Mental health and safety on campus

Yuki Yamazaki, a clinical assistant professor of counseling psychology at Fordham University, said it’s notable that all seven deaths were of young, Indian men. She said she can’t help but think about the fact that it’s a demographic that often doesn’t seek mental health help, and one that engages in riskier behavior.

“It’s so expensive to study in the States and there’s so much pressure to perform well,” she said. “And of course, to get a good job, to maybe obtain a visa. It just means as soon as you get here, you have endless amounts of pressure on you … Especially if your family has helped support you to get to this point.”

As a leader in his campus’ Indian American community, Shah says he’s seen firsthand the pressures that his fellow students face and the coping mechanisms they sometimes turn to. He said that, although motives weren’t clear in some of the incidents, he wondered about mental health as a factor.

“Everything is always driven by competition,” he said. “It’s a big detriment to mental health and it could also push you into, let’s say, drinking too much and going over the edge when it comes to that because you only have one or two days a week to have fun.”

When it comes to student safety, universities are operating within a limited scope, Dhingra said. And while campus might be a safe and happy place for minority students, a surrounding small town might not be.

“If you’re in rural Connecticut, or rural Indiana, that creates its own kind of concern,” he said. “‘Where do I feel safe?’”

Indians make up one-quarter of international students. Some parents might wonder about sending them abroad.

For those on the subcontinent, an American education has long been idealized, seen as a sure path to prosperity. And though experts don’t see that drastically changing, they say people are starting to ask questions: If it was their child, would their university keep them safe? Would they look for them if they went missing?

Indian media has picked up on this rising death toll, with prominent news outlets running stories that read, “Threat to Indian Students in U.S.?” and “American Dream or American Horror?”

Indians constitute more than 25% of all international students in the U.S., and Dhingra doubts headlines like these will lead to any significant drop. But for individual families, especially those who have to sacrifice so much to send their children overseas, America might fall lower on their list.

“Indians can go elsewhere for education,” Dhingra said. “There are other places that are safer … and people know that, that’s not a secret.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also call the network, previously known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com