HONG KONG — The 27th time was not the charm — and for one Chinese man it could mark the end of a lifelong quest to make it to university.

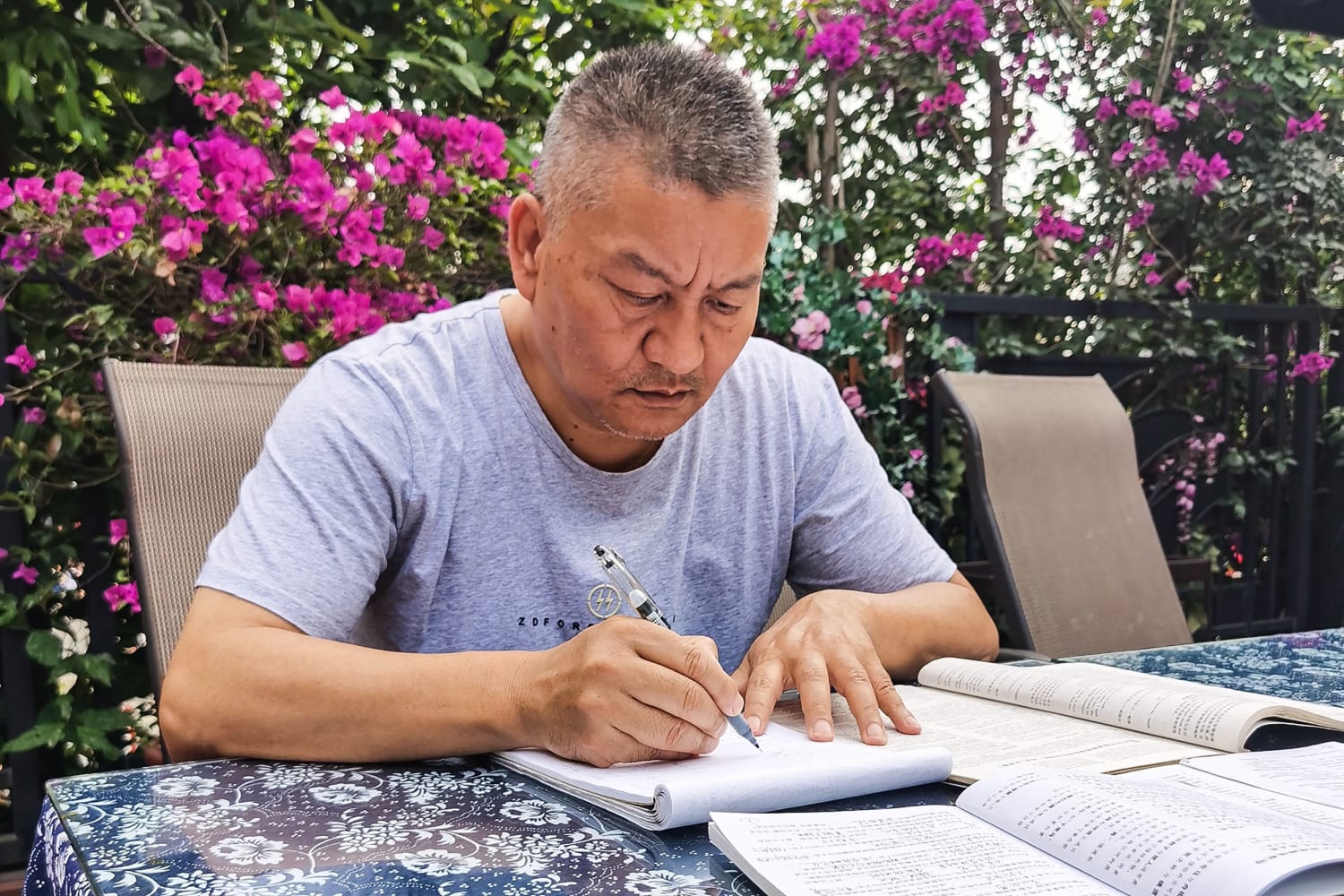

Liang Shi, 56, has tried for 40 years to get a satisfactory score on China’s national college entrance exam, known as the gaokao.

“I just admire intellectuals. I have been in awe of knowledge and well-educated people since I was a kid,” he told NBC News on Tuesday.

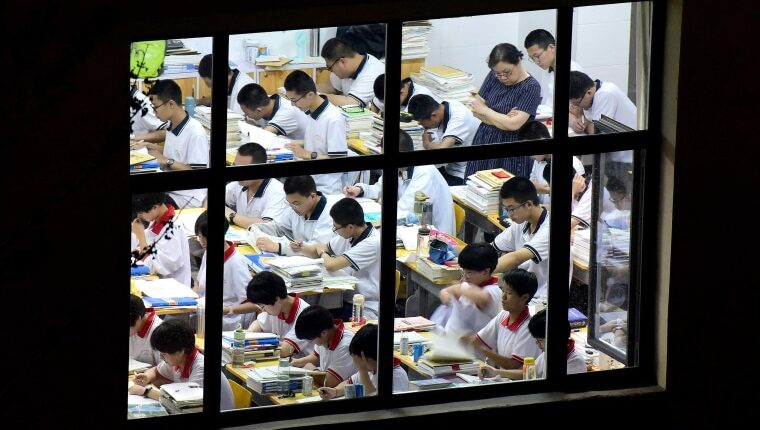

Regarded as one of the most challenging and competitive exams in the world, the gaokao is held once a year over two to three grueling days. Unlike in the United States and other countries where test scores are just one aspect of college applications, in China the gaokao is virtually the only determining factor in where most graduating seniors will attend university — if they get in at all.

Of the record 12.91 million students who took the exam early this month, fewer than half will gain entry into bachelor’s degree programs, based on data from past years.

Liang, a native of the southwest province of Sichuan, took the gaokao for the first time in 1983 but failed to score high enough for admission into any university, let alone his dream school of Sichuan University. In the decades that followed, he took the exam again and again for a total of 27 times, more than anyone else in China.

In the meantime he worked for a state-run factory, got married, lost his job when the company closed down in 1992 and started his own business. He was a millionaire by the late 1990s, when the average salary in China was around 8,000 yuan ($1,105) per year, according to official data.

Throughout all these years, he has never given up on the gaokao, taking it multiple times until he was no longer eligible due to his age. He started taking it again when the age limit was lifted in 2001, and has taken it every year since 2010.

In the years he was preparing for the exam, Liang said, he studied most days from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m., with only a short lunch break.

“I usually started my review process in September when students start their new academic year, and continued until June, when the exams begin,” he said.

“But my timetable is not as well organized as other students’. I have so many errands, after all,” Liang continued, adding that he studied three to four hours fewer per day than high school students preparing for the exam.

But his efforts were not rewarded this time, either. When Liang, like millions of others, received his results last Friday, he opened them on a livestream hosted by a Sichuan news outlet. To get into Sichuan University, he needed at least 600 out of 750 possible points, according to the historical database of college entrance exam admissions in Sichuan province.

His score: 424 — four points lower than last year.

“It’s such a pity!” said Liang, who expected to get at least the 450 points necessary for admission to a second-tier university.

He got his highest score, 469, in 2018, but was still not satisfied as it wasn’t enough to get into Sichuan University.

Though the gaokao is a once-in-a-lifetime experience for most students in China, Liang is not the only one who has taken it multiple times. Tang Shangjun, 35, has made 15 attempts in his pursuit of admission to one of China’s top universities, Tsinghua, which has an acceptance rate lower than Harvard’s.

“But it is just one or two very rare cases among tens of thousands of gaokao attendees, and it cannot represent any social trend or tendency in China,” said Peng Hongbin, a professor with expertise in education policy and law at South China Normal University in Guangzhou.

Most Chinese students and their families, especially those without the means to pay for study abroad, view the gaokao as the most important exam of their lives, one that will almost single-handedly determine the course of their future.

To prepare for it, Chinese high school students must study six subjects over three years, including the three required subjects of Chinese, mathematics and English. For the other three subjects, Sichuan students can choose a set from either the sciences (chemistry, physics and biology) or the liberal arts (geography, politics and history).

When students finally sit down to take the exam, many parents will wait anxiously outside.

Even for students who do well on the gaokao and graduate from university, the fierce competition continues: In May, China’s unemployment rate for people ages 16 to 24 was a record 20.8%, according to official data.

Surging university enrollment in China has also made bachelor’s degrees less of an advantage than they used to be. State media reported in May last year that the employment rate among graduates with bachelor’s degrees was lower than that of graduates from vocational schools.

“With the declining birth rate and the tendency of the aging population, China needs and is conducting educational reform now. Otherwise, the Chinese universities might fail to recruit students as there will not be enough people attending the gaokao,” Peng said. “Right now, the country is on track to diversify the admission standards in terms of college entrance. But with that goal far ahead, China still has a long way to go.”

Liang said he is unsure whether he will take the gaokao again next year.

“I’m afraid that my score may again fail to reach any university,” he said. “I may get nothing in the end. It’s not necessary.”

His friends have been supportive, Liang said: “They encourage me not to give up. It’s a shame to throw away the thing that you have been striving for so long.”

Some of his family members feel differently, including his son — who took the gaokao several years ago but studied separately from his father, who was preparing for it as well.

“He’s very averse to me taking the exams,” Liang said. “He felt embarrassed because I’m at such an old age and even though I have attended it so many times, I still can’t get a good score.”

Although bachelor’s degrees have become severely “devalued” due to increasing competition over the years, Liang said, “universities are sacred in my heart.”

“I still want to be an intellectual,” he said. “Achieving this goal will be my most important success.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com