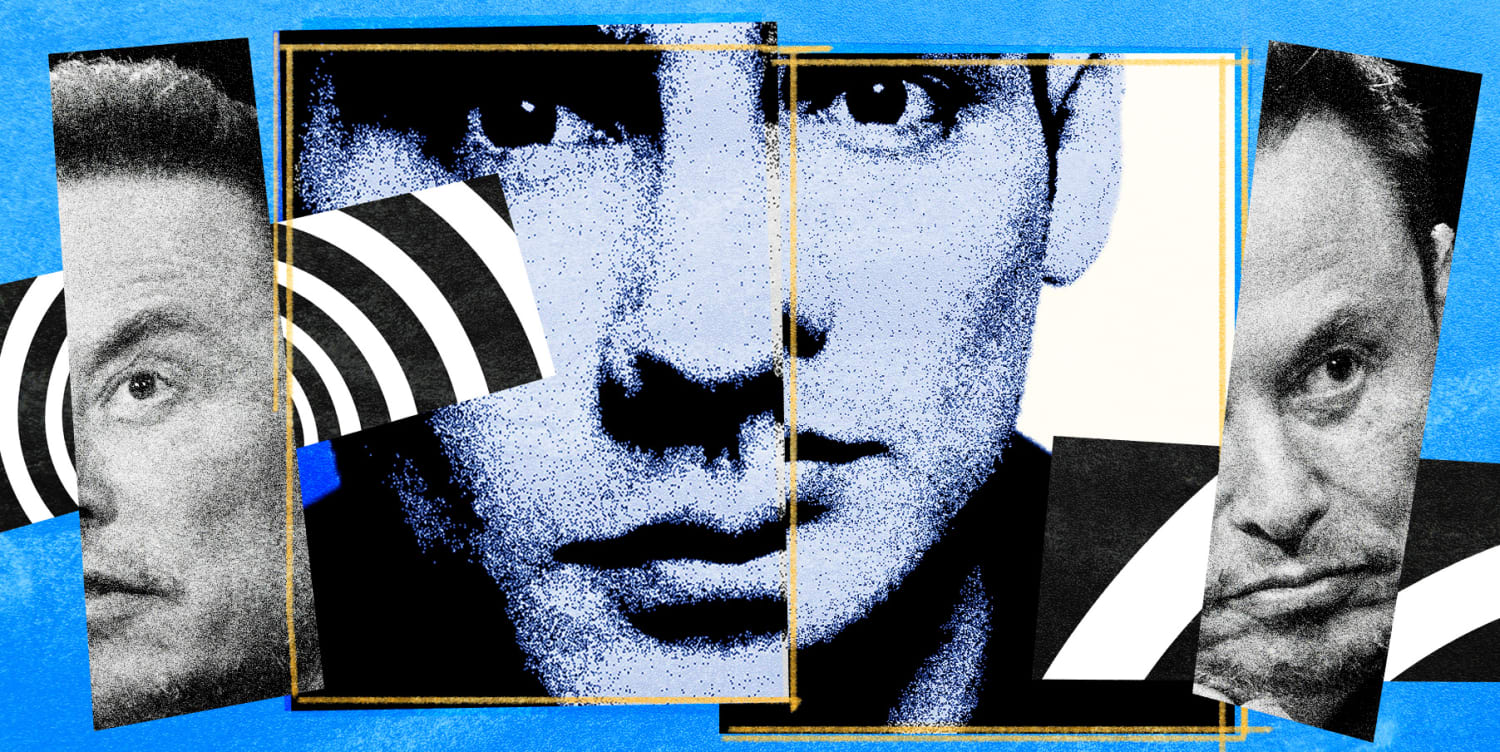

Mario Nawfal has emerged as one of the ascendant alternative media stars on Elon Musk’s Twitter, now named X, amassing more than 916,000 followers, receiving praise from Musk himself and frequently hosting some of the platform’s largest audio events.

Positioning himself as a combination of entrepreneur, business influencer and “citizen journalist,” Nawfal hosts and moderates “The Roundtable Show,” which he says brings in more than 6 million listeners per week on Twitter Spaces. The live audio chat has become a mainstay on the platform, featuring guests like former FTX CEO Sam Bankman-Fried and Hunter Biden, and receiving promotion from Musk. The crypto consulting company International Blockchain Consulting Group, of which Nawfal is the majority shareholder, says it is currently selling sponsorships for the show for up to $1 million.

But Nawfal’s meteoric rise from a little-known businessman to a seemingly omnipresent Twitter celebrity has been met by growing scrutiny from former colleagues who say Nawfal’s public persona of business and social media success has been built in part on broken promises and highly calculated and orchestrated growth hacking efforts.

NBC News spoke with seven people who said they invested with Nawfal or his companies, or worked with him at various points in his career. They painted a picture of an entrepreneur hungry for fame who has left unhappy collaborators in his wake, and they described incidents that trace a pattern of late payment or nonpayment — six said they had not been paid sums above $10,000 that they believe they were owed.

Communications from the individuals show they have been trying for years to get money back that they said Nawfal’s companies owe them. Some say they have received partial repayments, and others have lost hope.

Nawfal has spent money as quickly as it was made, according to former associates who said that at times his drive to find and fund successful projects or gain fame eclipsed his interests in paying people he owed money to.

“I thought Mario was always a smart guy, very kind, nice dude, but misinformed in his approach,” said Raj Lahoti, the co-founder of DMV.org, a privately owned consumer website, and a previous collaborator of Nawfal’s.

Sigmund Holtz, a former contractor of one of Nawfal’s companies, said, “Mario definitely moves from one thing to another, with high speed and intensity, and he prioritizes things in his life, at nearly any cost, that are going to have the biggest impact on himself and his business .”

Beyond issues of owing money, some former Nawfal associates have said they observed business practices that worried them enough to notify authorities.

Three former contractors and employees told NBC News that they reported Nawfal to authorities in the U.S. and abroad, including the Securities Exchange Commission and the FBI. NBC News reported in June that Holtz said that he was contacted by someone who identified themselves as an SEC representative and who asked him to provide details about Nawfal. Another former associate said he was instructed by the FBI to maintain potential evidence related to his interactions with Nawfal after he made an initial report to the agency.

As people have been scrutinizing Nawfal’s business practices, the authenticity of his social media success has also been questioned.

NBC News reviewed communications and documents that detailed a plan from a digital marketing company to boost Nawfal’s engagement on Twitter with over 1,000 “new accounts” and “inorganic engagement,” just as Musk was pushing Twitter to be more transparent about coordinated engagement campaigns on its platform.

In a 90-minute interview, Nawfal roundly denied many of the accusations, saying that he’s been a victim of a campaign waged by disgruntled former employees and associates. He acknowledged he had made mistakes and still owes some people money, but promised he would pay them back.

Nawfal’s entrepreneurial efforts go back to at least 2013, when he founded what he said was his first business, the juicer and blender company Froothie.

Froothie still operates today, and appears to still be generating profits for Nawfal. But critics have pointed to some blemishes in the company’s history as the beginning of a pattern of ethically dubious business practices.

In 2015, it paid a $10,800 penalty to Australian regulators for allegedly deceiving customers by advertising a misleading sale price. And in 2017, Froothie was sued by Juicero — the company that became a viral punchline after it was discovered that its juice bags could just be squeezed by hand — alleging Froothie was attempting to distribute machines that infringed on its intellectual property. The case was dismissed three years later when a judge ruled that the company was not then advertising in the U.S.

Mark Fidelman, a marketing executive, told NBC News that his company contracted to help Froothie in 2017 but that after an initial payment, Froothie stopped paying its bills and still owes his company over $6,000 six years later.

When asked if Fidelman had considered legal action, he said he was reluctant to go that route because Nawfal lives in Dubai.

“I don’t know what the rules are for Dubai, so even if I get a judgment, do they cooperate with those judgments?” he said.

In response to questions about Fidelman’s claims, Nawfal said that Fidelman was requesting payment that wasn’t previously agreed upon.

Nawfal’s aspirations weren’t limited to Froothie, and in the years leading up to the pandemic he worked to build a following and a public brand for himself. In 2017, he founded International Blockchain Consulting Group. In 2020, he co-founded another blockchain-related company, NFT Tech.

It was on the audio chatroom app Clubhouse and its pandemic-fueled boom where Nawfal started to gain some internet fame. He created an account that quickly drew over 50,000 followers and hosted larger chats with well-known personalities including the movie director Michael Bay. The playbook he developed foreshadowed the sizable rooms he would host on Twitter.

But Nawfal’s fame on Clubhouse was short-lived. Nawfal told NBC News that he was temporarily suspended from the platform following criticism from “an individual with a significant following.”

In 2021, Jason Calacanis, a tech entrepreneur who is close to Musk and who has 741,000 followers on Twitter, criticized Nawfal for participating in a group on the platform that he compared to “a cult.” The group organized large chat rooms around business expertise, titled, “THE MASTERCLASS.” Many of them also sold online entrepreneurship coaching.

At the time, and in response to a request for comment for this article, Nawfal denied ever having sold coaching.

A 2019 website that remains active advertised paid courses and coaching from Nawfal, directly linking to his personal website and YouTube channel. It’s no longer possible to purchase courses on the site, and Nawfal denies that the site advertising paid courses belongs to him.

Clubhouse and Calacanis did not respond to requests for comment.

Nawfal then found success on BitClout, a crypto-based social media platform where people can use cryptocurrency to buy and sell “creator coins,” meant to be a kind of stock market where people trade currencies tied to the brands of famous people and influencers. Nawfal quickly became a major personality on BitClout by frequently posting on the platform and investing money into peoples’ creator coins as well as his own.

Lahoti, the DMV.org founder, said he and Nawfal entered a deal that went sour, and that he confronted Nawfal over what he believed was a $50,000 debt related to BitClout investments.

In Telegram exchanges from 2021 between Lahoti and Nawfal reviewed by NBC News, Nawfal said, “I’m happy to sort it and make you whole” after Lahoti asked for the money and told him he would speak about the debt publicly.

Lahoti said he was paid less than half of the $50,000. He added that he eventually forgave Nawfal and said it became not worth the trouble to pursue the money but still wants to raise awareness about Nawfal’s business practices. Nawfal said in a statement that he “partially reimbursed” Lahoti but that he considers them even after accounting for separate losses he says he sustained in other investments with Lahoti, who Nawfal says “reneged on his promise to compensate him.”

Two people told NBC News that they remember Nawfal used BitClout as a venue to attract investors to a separate “friends and family” fund. They said that they invested in the fund but have yet to receive the promised repayment of their initial investment.

Two investors, who both asked to remain anonymous to avoid any potential backlash from Nawfal’s supporters online, said they invested a total of $23,000 in the fund in 2021, which was documented on contracts that were structured as loan agreements between the investors and one of Nawfal’s companies. One agreement was signed by Nawfal and the other was signed by his mother, both serving as legal signatories for his company, International Blockchain Consulting (IBC).

The contracts gave them the right to request repayment of their entire base investment.

Both investors provided NBC News with chat logs showing attempts to solicit repayment, but said they’ve received no money from IBC or Nawfal. One investor requested his money back in March 2022. The other investor did so last month.

James Armstrong, a single father in Australia, said he signed a similar contract, investing $70,000 in October 2021. Armstrong had just received an insurance payout after he was hit on his motorcycle by a truck — an accident that left him unable to reliably work. He said he thought the investment fund might be a good way to help him build up enough funds to buy property and establish financial stability.

Armstrong said that he’s received only about $45,000 of his initial $70,000 investment nearly two years after requesting repayment.

“It was a nightmare just getting those amounts,” Armstrong said. “It shouldn’t take a year of begging.”

Armstrong said he doesn’t have the money to afford a lawyer to take Nawfal to court.

When asked about Armstrong’s case, Nawfal said in an interview on June 28, “he’s got his money back, I’m sure.”

In messages sent to Armstrong on July 10, Nawfal said, “Regarding your last 30k, i will sort for you and get back to you.” Nawfal said he would “sort it” by the end of July.

Three weeks later, Armstrong said an IBC contractor asked him to sign a new contract. He signed it, but said he was sent a message afterward saying: “Please be reminded that no newspaper should publish any story involving you. In case any such story arises, please ensure immediate withdrawal. As it will jeopardize the contract and as such the payment plan.”

Armstrong said he thinks the incident shows that Nawfal is “using my own money to try and buy my silence.” In a WhatsApp message, Sulaiman Ahmed, the IBC contractor who contacted Armstrong, said that “we conducted ourselves transparently” and that “Mr. Armstrong willingly entered into the agreement, expressing his satisfaction.”

“If you want to find something in my entire history that’s not fully kosher, it’s probably that,” Nawfal said about the fund. “This is one thing, I probably shouldn’t have done it.”

“And I’m sticking with my liabilities and at the end of the day, I’ve never done anyone wrong. And I’ll be able to, you know, make whole anyone,“ Nawfal said.

Nawfal maintained that he still intends to eventually pay back everyone who invested in the fund.

Nawfal’s stumbles around BitClout and Clubhouse did little to halt the momentum he had begun to gain as an influencer, and 2022 would be a big year for his public profile as he shifted more attention to Twitter’s audio discussion platform, Spaces. Nawfal hosted dozens of spaces, mostly focused on developments in the crypto world. But it was the collapse of FTX and attention from Musk that supercharged his rise on social media.

On Nov. 12, 2022, Musk joined a Spaces discussion Nawfal was hosting about FTX’s collapse. Musk’s comments during the discussion made headlines around the internet, and Nawfal’s burgeoning discussions would subsequently become a destination for many pro-Musk voices on the platform. About a month later, Nawfal would host a space to do live coverage of the “Twitter Files,” a series of threads composed of internal communications at Twitter that Musk and the series’ promoters suggested showed meddling with free speech by social media companies and some members of government. Musk made an appearance in that discussion, too.

But as Nawfal’s profile rose, some of the people close to him began going public with allegations of nonpayment and broader allegations of illegal activities within Nawfal’s businesses. Nawfal also became the subject of online scrutiny after Christopher Zakrzewski, who goes by Upper Echelon on YouTube, began posting a series of videos in November calling Nawfal’s business practices into question.

Nawfal and IBC sued Zakrzewski last month, claiming the YouTuber had defamed him in the videos. After publishing a YouTube video about the lawsuit, Zakrzewski raised over $25,000 to fund his legal defense.

In the suit, their attorney contested 27 specific statements from Zakrzewski’s videos, which made a wide range of allegations. In one video, Zakrzewski analyzed a series of invoices that appeared to be submitted by Nawfal on behalf of IBC to NFT Technologies, another company that he co-founded and served as CEO at.

In the video, Zakrzewski alleged, citing unnamed sources, that the invoices represented specific work done by IBC employees that actually hadn’t been conducted or salaries that weren’t paid out. The lawsuit against Zakrzewski contests this point.

Jason Coles, co-founder of NFT Tech, also expressed concerns about invoices from IBC in a December call. Chet Long, who advised IBC and co-hosted numerous Twitter Spaces with Nawfal, provided NBC News with a recording of a phone call between himself, Coles and Holtz, in which Coles can be heard questioning the fundamentals of invoices from IBC to NFT Tech, saying he believed the company was being overcharged by IBC and Nawfal. “So either it’s all bulls—. Or, like, basically, either your accountant is bull. Or you siphoned money from NFT Tech and left us holding the bag,” Coles can be heard saying in the call.

Nawfal said that the invoices submitted to NFT Tech were accurate representations of the cost of the work, and that he was actually “doing favors” for NFT Tech by not charging more or pursuing other jobs.

Several former associates of Nawfal have mentioned the invoices, among other topics, in their own complaints about Nawfal.

Heijdenrijk, the former IBC executive, spoke out in December against Nawfal, as previously reported by NBC News, claiming that he was owed $60,000 in back pay. He made a similar claim about the invoices to Germany’s financial regulatory body, where NFT Tech is publicly listed, saying IBC billed for “non-existing services.”

In June, Long told NBC News that he was owed $27,000 by IBC, which Nawfal denies.

Long also said he cited the call with Coles in a report he made to the FBI, accusing Nawfal of money laundering, tax evasion and embezzlement. Long said that in a call with an FBI representative, he was told to preserve an old cellphone as potential evidence. The FBI declined to comment in June and for this article.

It’s not clear what steps, if any, the FBI and SEC have taken since the NBC News article was published in June.

Aside from the lawsuit against Zakrzewski, Nawfal has taken legal action against other former employees and individuals who have commented about his businesses.

Heijdenrijk previously told NBC News that he received an arbitration request from IBC seeking damages of over $5 million, claiming that Heijdenrijk had broken his nondisclosure agreement with the company. On July 26, as NBC News was reporting this article, Heijdenrijk said legal representatives for IBC and Nawfal sent him a letter demanding that he publish on Twitter that he had made false statements about Nawfal, threatening legal action.

In addition to publishing claims that Nawfal has fallen short of his word in business, Heijdenrijk also published allegations that raise questions about the tactics Nawfal used to build his brand as a “citizen journalist” on Twitter.

Documents made public by Heijdenrijk appear to show how a specialty firm helped Nawfal’s team attempt to boost his Twitter presence and gain traction on its audio Spaces with the use of “inorganic engagement.”

In June, Heijdenrijk posted part of a pitch deck that detailed a plan to increase Nawfal’s Twitter engagement — just a few months after Musk said his acquisition was on hold over concerns about “spam/fake accounts.”

Screenshots of a group WhatsApp chat posted by Heijdenrijk, along with additional documents and text messages viewed by NBC News, appear to show a discussion with representatives from a company called Winn.solutions. The messages include the company offering “growth hacking” services that guaranteed engagement from a “personal network of ‘super-fan’ accounts” for Nawfal’s accounts, using a mix of “inorganic” and “organic” engagement.

The screenshots show that the company activated its services multiple times on Nawfal’s account, and that two representatives of IBC asked the company if they could do similar boosting with Nawfal’s Twitter Spaces.

Artificial engagement to boost following on Twitter is explicitly against the platform’s policies, and Musk has personally said he is interested in prioritizing reducing the number of spam accounts on the site. But the screenshots published by Heijdenrijk show that “inorganic engagement,” as it was referred to by Winn.solutions CEO Jarred Winn, may have been used to boost a Twitter creator who Musk has personally promoted.

Heijdenrijk and another former employee said that Winn told them his company engaged in a practice sometimes known as device farming, where numerous individuals typically in offshore locations are paid to perform coordinated digital tasks, which could range from engaging with specific tweets to joining Twitter spaces.

At times, several employees from the IBC team showed hesitance about employing Winn’s practices, expressing concerns that the company’s methods could end up hurting Nawfal’s account. But eventually, IBC agreed to collaborate with Winn’s company.

Nawfal said in a statement that IBC used Winn’s services for three months, but that he wasn’t directly dealing with Winn.solutions and pushed back on the use of some of their services. The statement also emphasizes that Winn was not selling bots, “but instead utilized groups of real accounts.”

Nawfal has also begun to publicly push back against the claims made about his business practices.

In July, he tweeted that he had become a victim of the mainstream media’s “dark side as they began to tarnish my image,” referring to the article by NBC News, and highlighting other people who he said had been unfairly criticized in the media.

Musk responded to the tweet: “Just ignore.”

On July 27, Nawfal published a lengthy Twitter post about the lawsuit against Zakrzewski titled, “WHY I AM SUING A YOUTUBER AFTER MONTHS OF CONSTANT ATTACKS | HOW HE MANIPULATED HIS AUDIENCE & VICTIMIZED HIMSELF FOR ENGAGEMENT.” Nawfal said that he believes Zakrzewski’s videos are part of a coordinated attack against him that he will eventually expose: “Soon, I will also begin to gradually post evidence demonstrating coordinated attacks and planned lies by an individual who’s been framing me for the past 12 months.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com