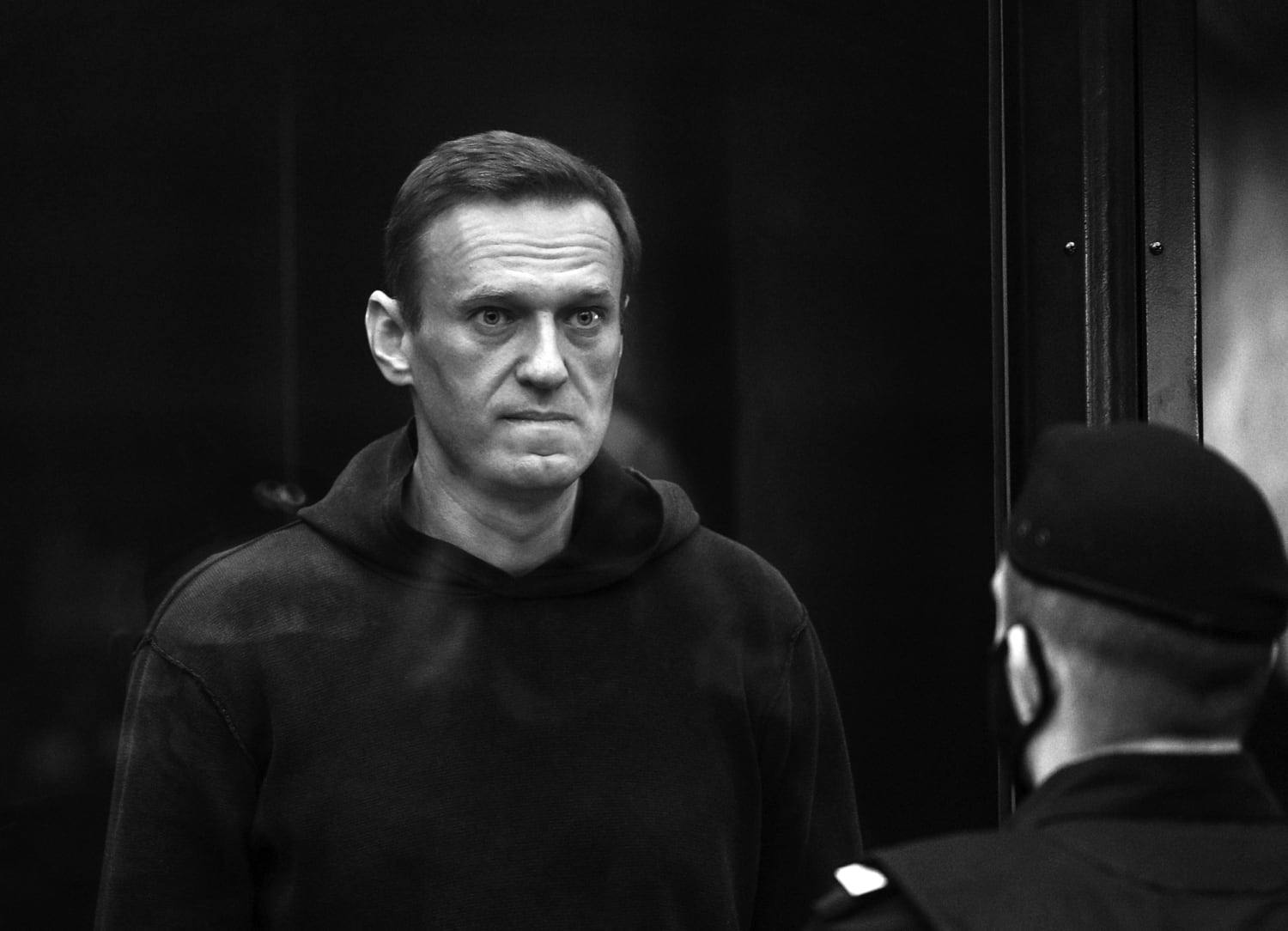

Alexei Navalny was poisoned by Russian state security officers and yet still chose to return. Predictably, he was arrested and sentenced to prison. This courageous act, coupled with the release of a damning video about President Vladimir Putin’s wealth and large protests across the country, have presented Putin with perhaps the greatest challenge to his 20-year presidency. That challenge culminated Tuesday in a Moscow courtroom with Navalny sentenced to more than two and a half years in a penal colony.

Navalny frames his mission as a personal duel with Putin, but his opposition crusade is taking place amidst three deeper currents that give his message special bite now.

Navalny frames his mission as a personal duel with Putin, but his opposition crusade is taking place amidst three deeper currents that give his message special bite now. First, living standards for Russians have been flat for a decade and the people are fed up. Key to Putin’s rise to power and popularity was a massive increase in household income and a sharp decline in poverty in his first decade in office, but those days are long gone.

Russia’s economy is not going to collapse anytime soon. The Kremlin has more than $500 billion in reserve funds, little debt, and relatively low inflation. Going forward, most observers expect economic growth of 1-2 percent, but there is little public faith that the government can change the economic course as powerful vested interests benefit from the status quo. The public consistently rates economic problems as its primary concern.

Second, Navalny’s call to protest is taking place in the shadow of recent protests in neighboring Belarus. Alexander Lukashenko has ruled Belarus for 26 years with few public displays of opposition, but, to the surprise of all, Belarussians have taken to the streets every weekend for months to protest massive vote fraud in the presidential election of August 2020. The government’s response to the protests has been brutal, but protests continue, if on a much smaller scale than in the summer. Lukashenko has survived these demonstrations with an assist from Putin, but these events have emboldened the Russian opposition. If mass demonstrations were possible in Belarus, then surely they are in Russia, as well.

Events in Belarus also may have changed the Kremlin’s strategy for dealing with Navalny. For a decade, the Kremlin felt making him a martyr by locking him away would be more damaging then allowing him to make noise as a free man. But the surprising political turbulence in Belarus may have reversed that calculation.

Third, Putin’s decision to change the Constitution to allow him two more six-year terms in office disillusioned many young Russians who desire political change and form the core of Navalny’s political support. In March 2020, Putin pushed through a packet of amendments that, among other things, canceled term limits for his first three terms as president and allowed him to run again in 2024 and 2030.

Public response to these efforts were mixed at best. The amendments passed by a comfortable margin, but this was due in part to a host of popular measures, such as increasing pensions and raising the minimum wage, that were included in the up or down vote on the entire packet of amendments. Public opinion surveys from the spring of 2020 show that about one-third of Russians want Putin to stay in office, roughly one-third want him to step down as president and remain active in politics, and one-third want him to retire.

This is not the first time that Putin’s decision to return to the presidency has sparked large street protests. In September 2011, then-Prime Minister Putin announced that he would run for the presidency in March 2012, a very strong signal that he had no intention of leaving office. Following parliamentary elections in early December of that year, hundreds of thousands of Russians took to the streets to protest election fraud, corruption, and Putin’s pending return to the presidency.

These concerns returned with the passage of the constitutional amendments in March 2020. Focus groups with young Russians conducted more than a year ago point to the absence of any hope for political change as one important motivation for their political activity, and surveys from May 2020 showed that 40 percent of young Russians were willing to protest to advance their cause.

As these deeper tides help feed the current protests, the sentencing of Navalny is not likely to quell opposition to the government anytime soon. On the other hand, it will be difficult for Navalny’s team to continue to organize protests on a large scale. Protesters face a pandemic, the Russian winter, and a considerable likelihood of arrest and brutal treatment by riot police. Moreover, Putin remains popular, particularly with older Russians. But the absence of protests does not mean the absence of opposition. Putin’s immediate challenge is to deal with Navalny and the protests, but the broader and more difficult challenge will be to change the deeper currents driving opposition to his government.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com