His image can be found on T-shirts at California markets, and fans still listen to his raspy voice singing the corridos, or Mexican ballads, that made Chalino Sánchez famous.

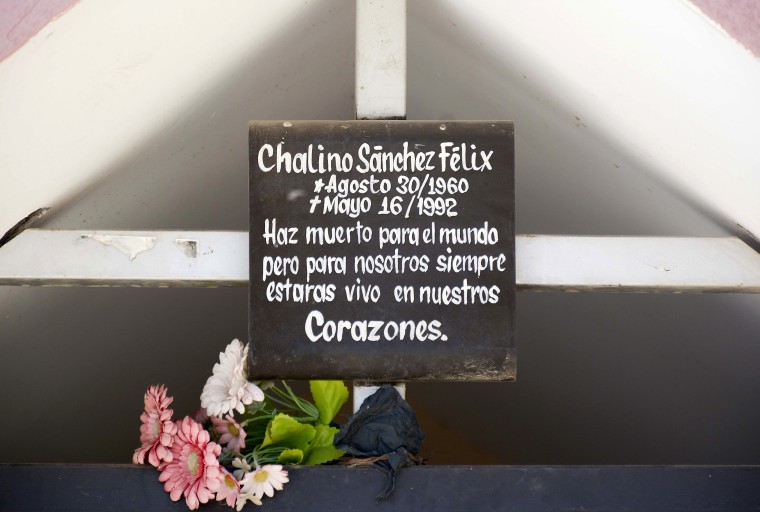

Decades after he was found shot to death when he was 31 years old, his allure has only been compounded by a popular podcast that has revived interest in the “King of Corrido.”

It wasn’t easy to tell Sánchez’s story — full of music, corridos but also violent episodes — taking into account that he was shot in 1992 and that the few confirmed details about his death are full of contradictions.

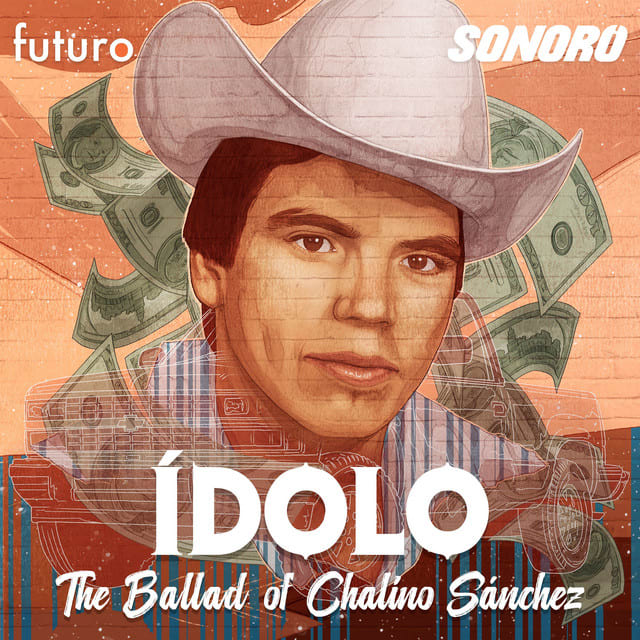

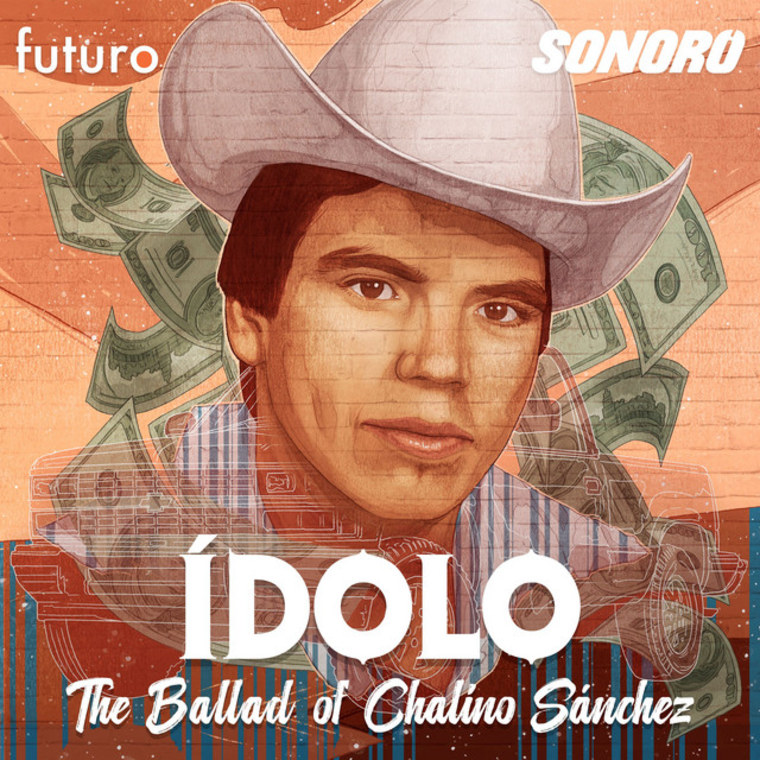

But journalists Erick Galindo and Alejandro Mendoza — authors and co-hosts of “Ídolo: The Ballad of Chalino Sánchez” — together with the production team of Futuro Studios and Sonoro found a way to tell the story and engage whoever hits play.

The bilingual podcast is almost one year old, and since then, the impact has been enormous.

“Ídolo” topped the podcast charts after its launch, and it has been described as “a tribute to the many things Chalino paved the way for” by Podcast the Newsletter and as a series that “wastes no time in hooking you into the mystery surrounding his death” by renowned Los Angeles outlet L.A. Taco.

“I don’t think anyone imagined that it would be as big as it has been,” Galindo said in an interview with Noticias Telemundo. “It ended up being the No. 1 podcast in Mexico. … I remember seeing the charts and it was in the top 100 in all countries. It’s still in the top 100 podcasts today, a year later, and people recognize me from the podcast. … They’re like, ‘OMG, you’re Erick Galindo!’”

The podcast, with a version in English and one in Spanish has made it possible to connect with very different audiences, not only by nationality, but also by age. “It’s the first podcast my parents listened to,” Galindo pointed out.

Even Sánchez’s wife, Marisela Vallejos Félix, told Galindo that she didn’t expect the podcast would be so popular.

Written by Galindo and Mendoza as if it were a thriller, the chapters investigate the possible theories surrounding the life and death of the singer. Sánchez was born and died in the north of Mexico — in Culiacán, Sinaloa — but he was well known and continues to be very popular on the other side of the border, especially in Los Angeles, where he lived for several years and achieved his dream of becoming a popular singer.

The result is an emotional story, set to music by an original “corrido” created especially for the podcast.

A podcast narrated by a pocho and a chilango

Galindo, whose family is from Culiacán, was born in the U.S. and remembers how shocking Sánchez’s death was for him and his relatives.

In the case of his older brother, it was literal shock: He had come home visibly affected after learning that his favorite corrido singer had been shot to death, according to the writer in the first episode of the podcast. He wanted to put a cassette with the artist’s hits in the family’s rickety tape recorder, but in trying to remove another stuck cassette with a screwdriver, he was shocked and passed out. When he was barely conscious again, he said between sobs, “They killed Chalino.”

The anecdote shows the deeply personal touch that he and Mendoza give to the narrative, drawing on their own experiences, which ended up producing unique versions of the same story — each with a completely original language and approach.

“We started thinking that it would be an exact translation from English to Spanish and vice versa. … But when we started writing, we realized it wasn’t the same story,” Galindo said.

“If you listen to the two episodes, in English and in Spanish … you will see that the perspective is different,” Galindo said, “one is the perspective of a ‘pocho’ (slang for Mexican American) living in the United States and the other is that of a ‘chilango,'” (referring to someone from Mexico). The Spanish one represents a look from the Mexican states of Jalisco, Michoacán and Sinaloa, which are epicenters of the war against the drug cartels and much of the violence that shakes the country.

The figure of Sánchez is an archetype for many Mexicans because of what he represents, Mendoza said, “a bit like the stereotype of the brave, brave man forging ahead, who has a clear objective and is going to achieve it, who does not leave anyone behind and who had a dream and fulfilled it.”

Sánchez represents the experiences of migrant men and women in the United States. He was born on a ranch in Culiacán, in the bosom of a traditional, poor and numerous Mexican family. His father died when he was only 6 years old, and he had to learn to make a living with his seven brothers.

An outlaw-turned-singer

The podcast takes the listener into the controversy around the late singer, including accounts of Sánchez’s participation in more than one shooting, including an account of a shooting at a party in Culiacán when he was “barely a short teenager,” as Mendoza narrates in Spanish, an event that forces Sánchez to immigrate to California.

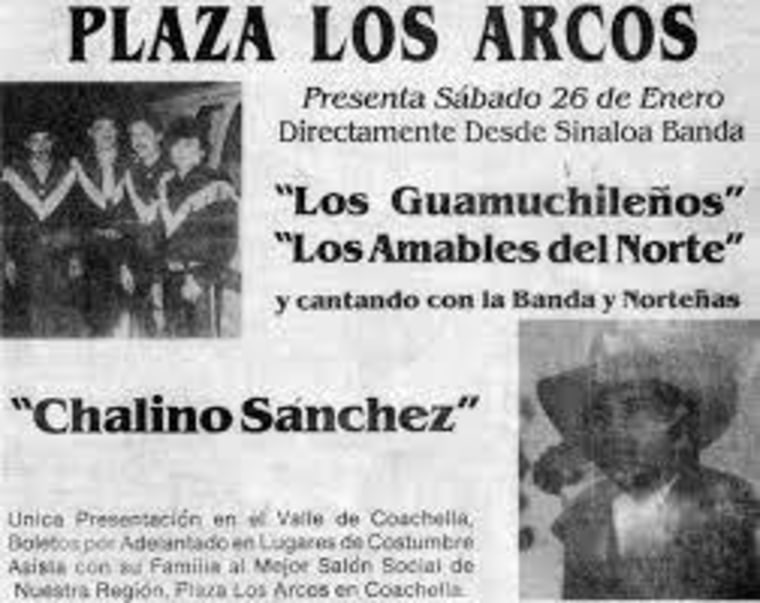

He also shot into the audience in the middle of a concert at the Plaza Los Arcos bar in Coachella, California, returning fire after he was shot. He wasn’t charged.

The podcast narrators skillfully weave together the most relevant events in Sánchez’s life with theories about his death: whether he was killed in revenge for the shooting at the party in Culiacán when he was a teen, whether the cartels wanted him dead because of the lyrics to his songs, was it because of a possible love triangle with a furious drug lord, or was it because of possible links to a drug trafficker, among other hypotheses. Each episode is dedicated to one of these theories, and together they masterfully narrate Sánchez’s cinematic life.

Anecdotes and references to Sánchez’s songs and interviews with other legends of regional Mexican music — including a very brief interview outside a parking lot worthy of a movie script with Don Pedro Rivera, one of the pillars of the industry and the father of Lupillo Rivera and the late singer Jenni Rivera — round off the narrative and plunge the listener into the underworld of the music industry and drug culture.

“The regional Mexican genre is historically associated with drug trafficking and crime,” Mendoza pointed out. It’s a complex relationship that stems from a relatively simple principle: Artists talk about what they know, so in a country overwhelmed by crime, it’s not surprising that songs about bosses, kilos and machine guns abound.

“The regional Mexican genre tells stories that happen in the country, and if the country is submerged in violence, there will be a chronicler who talks about it,” Mendoza said.

There’s also humor, reflected in a scene from the second episode on how Sánchez and his future wife and mother of his two children, Marisela Vallejos Félix, met. It was Mendoza’s favorite anecdote.

Sánchez is driving through the streets of East Los Angeles and sees a woman he likes standing on the sidewalk getting wet in the rain. Then, he offers her a rid in his car, a gesture both gallant and arrogant.

For Mendoza, the scene says a lot about the two characters.

“He was exercising this image of power, like, ‘Hey, I have a car, I’m handsome, get in,’” he said. “And I love it because her response speaks of the character of the Mexican woman. … She said, ‘OK, I’ll get on, but you let me drive,’ and she drove, but she did it so fast that Chalino himself was scared. And well, he liked that.”

Between shootings, love anecdotes and theories about an unsolved crime, the narrators take the listener by the hand through Sánchez’s story, until his last days.

After the artist’s involvement in the Coachella shooting while he was on stage, he catapulted to fame.

After the shooting, he was hospitalized in serious condition after being hit by two bullets. But a few months later, when he was barely recovering, he made a risky decision that put him on a deadly path: He returned to Culiacán to sing to his people the corridos that made him famous.

He arrived in Sinaloa to present what would be his last concert on May 16, 1992. The concert was sold out, the audience sang along to all the songs and Sánchez was probably giving the performance of his life, the podcasters explain. In the middle of the merriment, he was approached by a man who handed him a note with a handwritten message, known in the singer’s fan circles as the “death note.”

What was written on that paper has never been revealed, but his composure changed when he read it. He threw it to the ground and continued playing, as if nothing had happened.

Hours later, still at dawn, he was found dead in a canal. He had his wrists and ankles bound and had been shot twice in the back of the head.

As Galindo narrates in the podcast, Sánchez’s death seemed like the foregone conclusion of his Wild West kind of life. Rumors about why he was killed started immediately: that he had faked his death to escape a possible attack, that the Mexican or U.S. government killed him, that he was a secret hit man for the cartels and got what he deserved.

Since Sánchez’s death, ranchera songs sung with a shrill and out-of-tune voice but with deep passion have gone from being something liked by a select few to becoming the most important musical genre in Mexico. With this, the figure of Chalino has become a true pop icon.

An earlier version of this story was first published in Noticias Telemundo.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com