PALISADE, Minnesota — On the edge of the Mississippi River in Northern Minnesota, Tania Aubid stares at the slushy waters that thaw a little more with every passing spring day.

Once the river is no longer frozen, she’s dreading the day that Canadian energy company Enbridge will be able to drill and lay down a new section of their Line 3 pipeline, a construction project about halfway finished that has sparked increasing environmental demonstrations and unrest from Native Americans and other climate activists in recent months.

“Sixty-eight million people rely upon this water that comes from up here in Northern Minnesota, and it goes all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico,” she said. “And along the way there are cities — people that drink straight from the river here.”

These wilds of Northern Minnesota, a place so beautiful the Northern lights dance across the sky, have become the new front line in tensions between climate protesters, some Native populations and Big Energy. The changing seasons will likely bring more attention to this fight, as more people are expected to populate the growing number of protest camps that have sprouted up along the path of the pipeline and work is allowed to progress beneath the river.

Enbridge’s Line 3 is a 60-year old pipeline that will partially be taking a new route with new construction in Minnesota. They are replacing a 34-inch pipeline with a 36-inch pipeline, and it now cuts along a different path than the original — 13 miles in North Dakota, 337 miles in Minnesota, and 14 miles in Wisconsin. The Minnesota phase of construction has been going on for four months.

When President Joe Biden moved to shut down the Keystone XL pipeline on his very first day in office, it gave new hope to activists who are desperate for him to renew a focus on Line 3.

“The number one issue to young voters is the climate, and they know that,” said Tara Houska, a member of the Couchiching First Nation, Anishinaabe and the founder of Giniw Collective. She was born in Northern Minnesota and has become a leader in this movement. “I thought that in terms of this project, and in terms of Dakota Access, that it opened a window into hearing a different answer.”

That window means that unlike the last administration, Biden’s team is at least talking to them.

“We’ve met multiple times with the White House with the Army Corps,” Houska said. “There’s a planned follow-up next week. I’m supposed to meet with Interior. There’s a conversation and a door that has been opened.”

In addition to climate concerns, activists have pointed to the fact that the pipeline travels directly through Native land given in the treaty of 1855 and through lands where Native tribes have been harvesting wild rice for decades.

“If [the pipeline] breaks, it will destroy the wild rice,” said Elizabeth Skinaway, a Sandy Lake Band member. “If indigenous peoples are telling you that, then you need to listen,” she added.

Enbridge says the construction will bring 5,000 new jobs, and they claim a $2 billion boost to the local economy. This replacement pipe, they say, is critically necessary to avoid a potential ecological catastrophe.

Just such a disaster occurred two decades ago when the pipeline ruptured in Minnesota, leaking 1.7 million gallons of crude oil to constitute the largest inland oil spill in the nation’s history, according to Minnesota Public Radio.

“If you’re really concerned about safety, we need this pipeline,” said Mike Fernandez, a senior vice president at Enbridge. “This is really like Biden says, ‘Build Back Better.’ So this is a modernization project to make sure that the pipeline is safe and to make sure there is no environmental harm.”

While there are still multiple lawsuits over this pipeline underway, Enbridge maintains they already went through all the proper avenues.

“This is a six-year long review,” Fernandez said. “There were scientific elements talking about pipeline safety itself, there were concerns raised all along the way. We had more than 70 public hearings, three state authorities that reviewed this process, permitted this process, and two federal government agencies reviewed this pipeline.”

On the ground, the expectation among protesters is that more people will come — as was the case with the oil pipeline protest at Standing Rock in 2017. Those present at that confrontation said they learned lessons they’re using now.

At a makeshift kitchen in the main camp, an activist who declined to share his name talked about the strategy of building multiple small camps rather than one large and how that’s a lesson learned from experience at Standing Rock.

“We are getting better,” he says. “They learn so that we learn. Having multiple camps set up is a part of that strategy.”

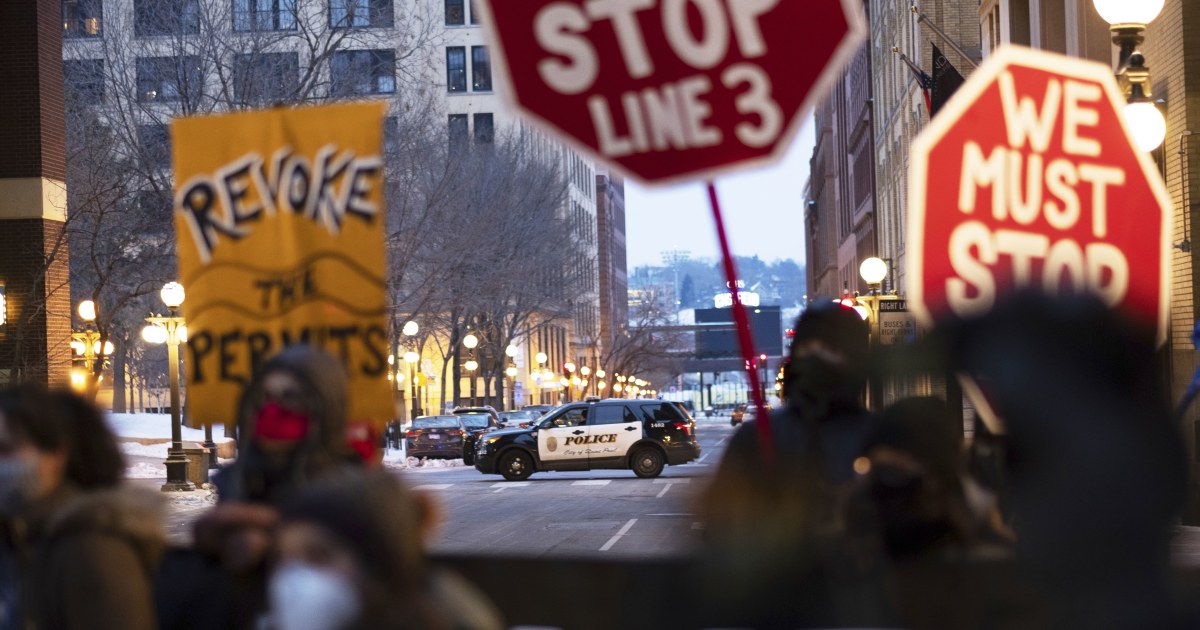

Also part of the strategy among some of the most fervent activists have been demonstrations with the expectation of arrest. Houska and several others were arrested on Thursday during a protest at one of the Enbridge construction sites.

“We’ve had over 200 people arrested fighting Line 3 over the winter,” she said before she was taken into custody this week. “Through the cold 30-below zero, you got people crawling into pipes, risking their actual safety, fighting for the future.”

For now, the Biden administration finds itself jammed between two of the interest groups it has worked the hardest to court in the last few years. Biden positions himself not only as a president who puts a focus on climate, but also someone who would insure job creation and protect unions.

The White House hasn’t given any indication over whether they’re considering any kind of action related to this pipeline. “President Biden has proposed transformative investments in infrastructure that will not only create millions of good union jobs but also help tackle the climate crisis,” an official said in a statement. “The Biden-Harris Administration will evaluate infrastructure proposals based on our energy needs, their ability to achieve economy wide net-zero emissions by 2050, and their ability to create good paying union jobs.”

For now, unless any action is taken by the administration or in any of the current court battles, activists expect to see their presence and their actions here only escalate.

“I think I’m at a point where I’ve heard people refer to me as a radical person,” Houska said. “I don’t think that it’s radical to protect the Earth. I don’t think it’s radical to care so much for someone who isn’t born yet. I think it’s deeply powerful and it’s reconnecting to our own humanity, and who we are as people, we can’t live without the Earth. It’s that simple.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com