Two new cases presented Wednesday at the International AIDS Conference in Montreal have advanced the field of HIV cure science, demonstrating yet again that ridding the body of all copies of viable virus is indeed possible, and that prompting lasting viral remission also might be attainable.

In one case, scientists reported that a 66-year-old American man with HIV has possibly been cured of the virus through a stem cell transplant to treat blood cancer. The approach — which has demonstrated success or apparent success in four other cases — uses stem cells from a donor with a specific rare genetic abnormality that gives rise to immune cells naturally resistant to the virus.

In another case, Spanish researchers determined that a woman who received an immune-boosting regimen in 2006 is in a state of what they characterize as viral remission, meaning she still harbors viable HIV but her immune system has controlled the virus’s replication for over 15 years.

Experts stress, however, that it is not ethical to attempt to cure HIV through a stem cell transplant — a highly toxic and potentially fatal treatment — in anyone who is not already facing a potentially fatal blood cancer or other health condition that would make them a candidate for such a treatment.

“While a transplant is not an option for most people with HIV, these cases are still interesting, still inspiring and illuminate the search for a cure,” Dr. Sharon Lewin, an infectious disease specialist at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at the University of Melbourne, told reporters on a call last week ahead of the conference.

There are also no guarantees of success through the stem cell transplant method. Researchers have failed to cure HIV using this approach in a slew of other people with the virus.

Nor is it clear that the immune-enhancing approach used in the Spanish patient will work in additional people with HIV. The scientists involved in that case told NBC News that much more research is needed to understand why the therapy appears to have worked so well in the woman — it failed in all participants in the clinical trial but her — and how to identify others in whom it might have a similar impact. They are trying to determine, for example, if specific facets of her genetics might favor a viral remission from the treatment and whether they could identify such a genetic profile in other people.

The ultimate goal of the HIV cure research field is to develop safe, effective, tolerable and, importantly, scalable therapies that could be made available to wide swaths of the global HIV population of some 38 million people. Experts in the field tend to think in terms of decades rather than years when hoping to achieve such a goal against a foe as complex as this virus.

The new cure case

Diagnosed with HIV in 1988, the man who received the stem cell transplant is both the oldest person to date — 63 years old at the time of the treatment — and the one living with HIV for the longest to achieve an apparent success from a stem cell transplant cure treatment.

The white male — dubbed the “City of Hope patient” after the Los Angeles cancer center where he received his transplant 3½ years ago — has been off of antiretroviral treatment for HIV for 17 months.

“We monitored him very closely, and to date we cannot find any evidence of HIV replicating in his system,” said Dr. Jana Dickter, an associate clinical professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at City of Hope. Dickter is on the patient’s treatment team and presented his case at this week’s conference.

This means the man has experienced no viral rebound. And even through ultra-sensitive tests, including biopsies of the man’s intestines, researchers couldn’t find any signs of viable virus.

The man was at one time diagnosed with AIDS, meaning his immune system was critically suppressed. After taking some of the early antiretroviral therapies, such as AZT, that were once prescribed as individual agents and failed to treat HIV effectively, the man started a highly effective combination antiretroviral treatment in the 1990s.

In 2018, the man was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, or AML. Even when HIV is well treated, people with the virus are still at greater risk of a host of cancers that are associated with aging, including AML and other blood cancers. Thanks to effective HIV treatment, the population of people living with the virus in the U.S. is steadily aging; the majority of people diagnosed with HIV is now older than 50.

He was treated with chemotherapy to send his leukemia into remission prior to his transplant. Because of his older age, he received a reduced intensity chemotherapy to prepare him for his stem cell transplant — a modified therapy that older people with blood cancers are better able to tolerate and that reduces the potential for transplant-related complications.

Next, the man received the stem cell transplant from the donor with an HIV-resistant genetic abnormality. This abnormality is seen largely among people with northern European ancestry, occurring at a rate of about 1% among those native to the region.

According to Dr. Joseph Alvarnas, a City of Hope hematologist and a co-author of the report, the new immune system from the donor gradually overtook the old one — a typical phenomenon.

Some two years after the stem cell transplant, the man and his physicians decided to interrupt his antiretroviral treatment. He has remained apparently viable-virus free ever since. Nevertheless, the study authors intend to monitor him for longer and to conduct further tests before they are ready to declare that he is definitely cured.

The viral remission case

A second report presented at the Montreal conference detailed the case of a 59-year-old woman in Spain who is considered to be in a state of viral remission.

The woman was enrolled in a clinical trial in Barcelona in 2006 of people receiving standard antiretroviral treatment. She was randomized to also receive 11 months of four therapies meant to prime the immune system to better fight the virus, according to Núria Climent, a biologist at the University of Barcelona Hospital Clinic, who presented the findings.

Then Climent and the research team decided to take the woman off her antiretrovirals, per the study’s planned protocol. She has now maintained a fully suppressed viral load for over 15 years. Unlike the handful of people either cured or possibly cured by stem cell transplants, however, she still harbors virus that is capable of producing viable new copies of itself.

Her body has actually controlled the virus more efficiently with the passing years, according to Dr. Juan Ambrosioni, an HIV physician in the Barcelona clinic.

Ambrosioni, Climent and their collaborators said they waited so long to present this woman’s case because it wasn’t until more recently that technological advances have allowed them to peer deeply into her immune system and determine how it is controlling HIV on its own.

“It’s great to have such a gaze,” Ambrosioni said, noting that “the point is to understand what is going on and to see if this can be replicated in other people.”

In particular, it appears that what are known as her memory-like NK cells and CD8 gamma-delta T cells are leading this effective immunological army.

The research team noted that they do not believe that the woman would have controlled HIV on her own without the immune-boosting treatment, because the mechanisms by which her immune cells appear to control HIV are different from those seen in “elite controllers,” the approximately 1 in 200 people with HIV whose immune systems can greatly suppress the virus without treatment.

Lewin, of Australia’s Peter Doherty Institute, told reporters last week that it is still difficult to judge whether the immune-boosting treatment the woman received actually caused her state of remission. Much more research is needed to answer that question and to determine if others might also benefit from the therapy she received, she said.

Four decades of HIV, a handful of cures

Over four decades, just five people have been cured or possibly cured of HIV.

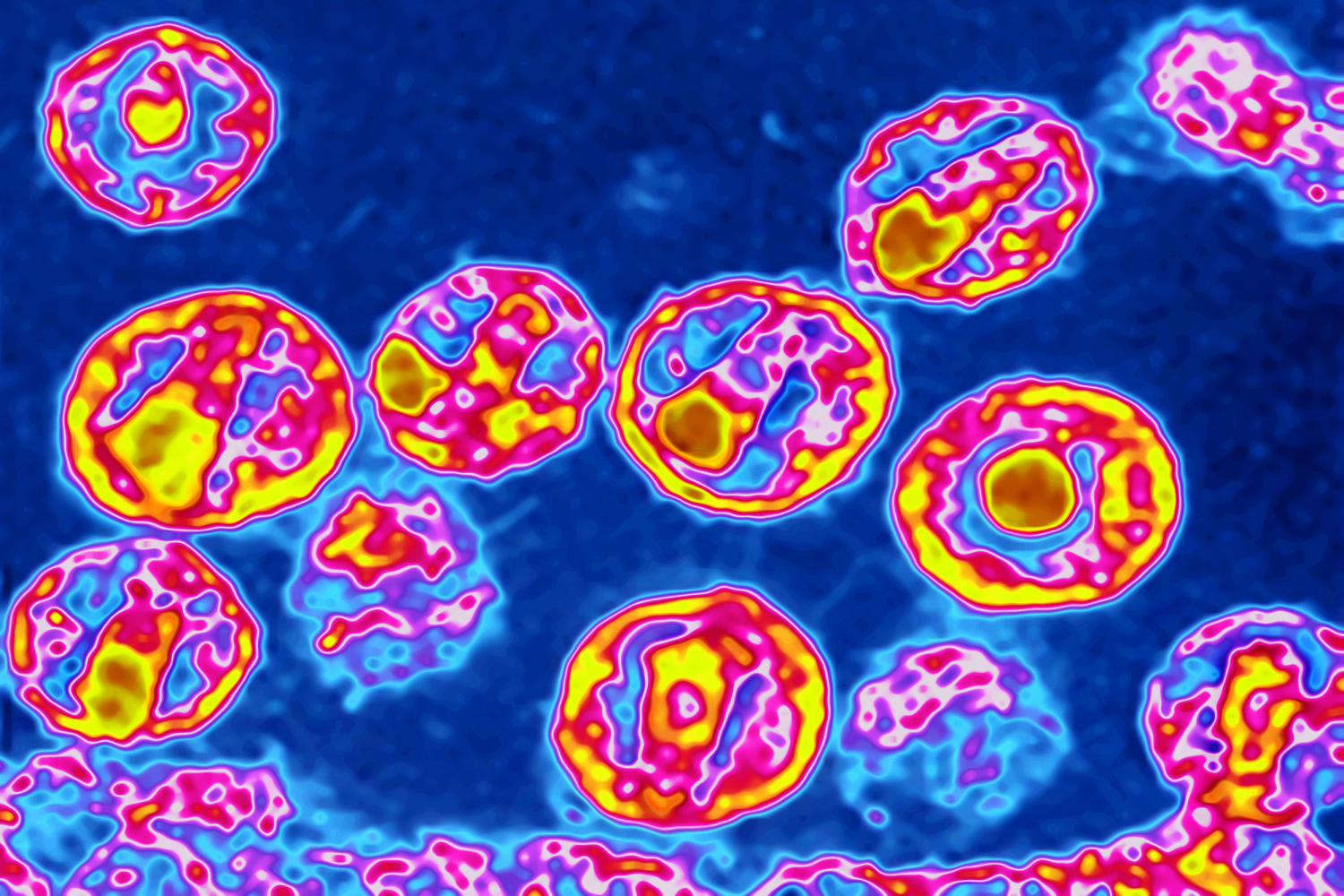

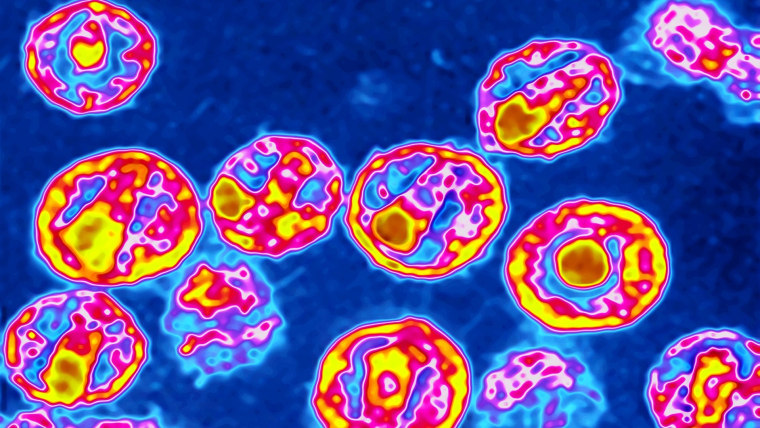

The virus remains so vexingly difficult to cure because shortly after entering the body it infects types of long-lived immune cells that enter a resting, or latent, state. Because antiretroviral treatment only attacks HIV when infected cells are actively churning out new viral copies, these resting cells, which are known collectively as the viral reservoir and can stay latent for years, remain under the radar of standard treatment. These cells can return to an active state at any time. So if antiretrovirals are interrupted, they can quickly repopulate the body with virus.

The first person cured of HIV was the American Timothy Ray Brown, who, like the City of Hope patient, was diagnosed with AML. His case was announced in 2008 and then published in 2009. Two subsequent cases were announced at a conference in 2019, known as the Düsseldorf and London patients, who had AML and Hodgkin lymphoma, respectively. The London patient, Adam Castillejo, went public in 2020.

Compared with the City of Hope patient, Brown nearly died after the two rounds of full-dose chemotherapy and the full-body radiation he received. Both he and Castillejo had a devastating inflammatory reaction to their treatment called graft-versus-host disease.

Dr. Björn Jensen, of Düsseldorf University Hospital, the author of the German case study — one typically overlooked by HIV cure researchers and in media reports about cure science — said that with 44 months passed since his patient has been viral rebound-free and off of antiretrovirals, the man is “almost definitely” cured.

“We are very confident there will be no rebound of HIV in the future,” said Jensen, who noted that he is in the process of getting the case study published in a peer-reviewed journal.

For the first time, University of Cambridge’s Ravindra Gupta, the author of the London case study stated, in an email to NBC News, that with nearly five years passed since Castillejo has been off of HIV treatment with no viral rebound, he is “definitely” cured.

In February, a research team announced the first case of a woman and the first in a person of mixed race possibly being cured of the virus through a stem cell transplant. The case of this woman, who had leukemia and is known as the New York patient, represented a substantial advance in the HIV cure field because she was treated with a cutting-edge technique that uses an additional transplant of umbilical cord blood prior to providing the transplant of adult stem cells.

The combination of the two transplants, the study authors told NBC News in February, helps compensate for both the adult and infant donors being less of a close genetic match with the recipient. What’s more, the infant donor pool is much easier than the adult pool to scan for the key HIV-resistance genetic abnormality. These factors, the authors of the woman’s case study said, likely expand the potential number of people with HIV who would qualify for this treatment to about 50 per year

Asked about the New York patient’s health status, Dr. Koen van Besien, of the stem cell transplant program at Weill Cornell Medicine and New York-Presbyterian in New York City, said, “She continues to do well without detectable HIV.”

Over the past two years, investigators have announced the cases of two women who are elite controllers of HIV and who have vanquished the virus entirely through natural immunity. They are considered likely cured.

Scientists have also reported several cases over the past decade of people who began antiretroviral treatment very soon after contracting HIV and after later discontinuing the medications have remained in a state of viral remission for years without experiencing viral rebound.

Speaking of the reaction of the City of Hope patient, who prefers to remain anonymous, to his new HIV status, Dickter said: “He’s thrilled. He’s really excited to be in that situation where he doesn’t have to take these medications. This has just been life-changing.”

The man has lived through several dramatically different eras of the HIV epidemic, she noted.

“In the early days of HIV, he saw many of his friends and loved ones get sick and ultimately die from the disease,” Dickter said. “He also experienced so much stigma at that time.”

As for her own feelings about the case, Dickter said, “As an infectious disease doctor, I’d always hoped to be able to tell my HIV patients that there’s no evidence of virus remaining in their system.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com