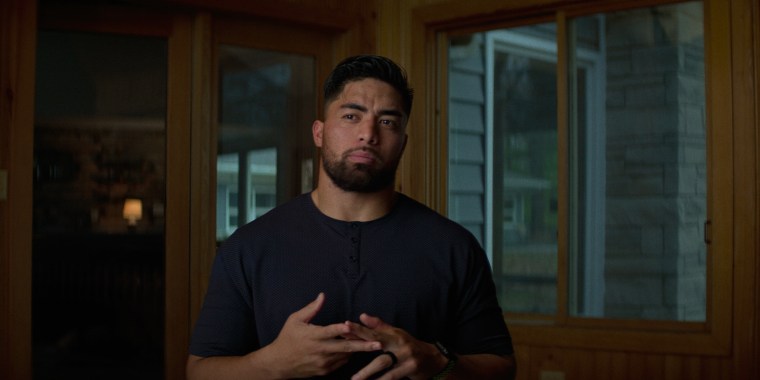

National Football League linebacker Manti Te’o says he’s moved past it all — almost. And it’s thanks, in part, to what he describes as embracing the “aloha spirit.”

Te’o, the victim of a major 2013 catfishing scandal that’s now the subject of the recent Netflix documentary, “Untold: The Girlfriend Who Didn’t Exist,” has been reflecting on how his Polynesian identity factored into the incident and backlash, as well as how his culture played a role in his subsequent healing,

“One thing that really separates us, from what I’ve known since I was little, is that we’re very, very loving. We’re very, very inclusive,” Te’o said. “That’s Polynesian culture at its purest in my opinion.”

Te’o rose to national fame nearly a decade ago after he had led the University of Notre Dame football team to an undefeated 2012 season amid the deaths of his grandmother and his then-girlfriend, the fictional Lennay Kekua. But early the following year, public opinion turned on Te’o after it was discovered that Kekua, whom he had never met in person, had been made up by Naya Tuiasosopo, who had used photos of another woman to pose as Kekua, a practice known as “catfishing.”

Te’o told NBC Asian America that as a football player who grew up in a tight-knit Pacific Islander community in Hawaii, it was Kekua’s shared Polynesian identity that was an undeniable factor in drawing him in.

“Everybody doesn’t want to be alone,” he said of finding a common culture with the person he thought to be Kekua. “Everybody wants to have somebody that can go with them through whatever experience they’re going through.”

With interviews from both Te’o and Tuiasosopo, in addition to friends and family members, the two-part documentary revisits the events. From Te’o’s rise as a Heisman trophy contender, who refused to miss games despite the sense of loss he said he felt, to the persona that Tuiasosopo, who has since come out as transgender, had manufactured while struggling with her own gender and sexual orientation, as well as the barrage of shifting media coverage, the episodes give new context to the wildly misunderstood incident.

While Te’o’s race and culture were not explicitly examined in the documentary, his Polynesian heritage and community are an inextricable part of both his story and who he is, he said. The linebacker, who most recently played for the Chicago Bears in 2021 and is currently a free agent, said that growing up, his Polynesian culture “was everything for me.” Not only was his culture infused across family and sports, his hometown of Laie, Hawaii, itself was also home to a close Pacific Islander community that made up almost 30% of the population. So when Te’o moved to South Bend, Indiana, for college, he said he experienced a major “culture shock.”

“The thing about Hawaii is it’s not like you could just drive and go into another state,” he said. “You’re in the middle of the Pacific. … when you leave Hawaii, everything is new, everything is just uncharted territory.”

He said he felt a sort of unspoken connection with the fictional Kekua, who purported to attend Stanford University and whose Samoan background meant they had the same “pillars of culture.” There was just an understanding between them, Te’o said.

“If I see somebody who I look like, who was supposedly raised the same way as me, there’s a lot of things that you don’t have to talk about. You just skip it over,” he said. “Like hey, I’m Polynesian. You’re Polynesian, you may not have been raised exactly like me, but we all understand in Polynesian culture … There are these beliefs and lessons that are taught to every kid.”

Though Te’o branched out and made friends across cultures, he said that being able to connect with someone of the same heritage gave him a sense of comfort and allowed him to have the “courage” to expand his social circles.

“I’m not sure if the media saw an opportunity to see what they thought a masculine person was and what a masculine person should be.”

Manti te’o, on the media chaos after the scandal broke.

Tuiasosopo, who went by Ronaiah at the time, denied NBC News’ request for comment, but in the documentary, she said that during Te’o’s football career at Notre Dame, she became a sort of “rock” for him. However, as Te’o ascended to stardom on the team, she said she felt she was “losing control” and by September 2012 she decided to “kill off” Kekua. Tuiasosopo posed as Kekua’s brother and called Te’o to tell him that the fictional girlfriend had lost a lengthy battle to leukemia. The news came just a few hours after Te’o had lost his grandmother.

“I’m telling you, I’m not proud and not happy with the decisions I made in that time,” Tuiasosopo said in the documentary.

As Te’o continued to attend practices and play games after the deaths, now armed with a “higher purpose” in honoring their lives and soldiering on through grief, his story became popular media fodder, rocketing him to front pages and often being described as an inspirational figure. The documentary also showed, however, that just as quickly as Te’o had become a national sensation, the media also was quick to exploit his story following a Deadspin investigation.

Deadspin revealed in January the following year that Tuiasosopo was behind it all. It was a tip to the outlet and a trail of missing obituaries, funeral announcements, student registration information, and other absent records that led to the discovery of Tuiasosopo’s catfishing. Te’o was promptly roasted on Saturday Night Live, made the focus of a humiliating meme challenge, and asked point-blank by high profile media personalities whether he was gay.

Though Te’o’s life, including his career prospects, collapsed around him, then-Deadspin intern Jack Dickey, who broke the story with writer Timothy Burke, claimed in the documentary that the outlet’s mission “was to make the mainstream sports media look foolish.”

“I don’t care what Manti’s sex life is. I don’t care what Ronaiah’s sex life is. That wasn’t our motivation at all,” Dickey said. “If anyone cared about that stuff, they were wrong to care about that stuff.”

Te’o described the chaos as a “snowball that became an avalanche and everybody was just in for the ride at that point.” He said he’s hesitant to pinpoint exactly what fed into the oftentimes malicious behavior he endured then. It’s impossible to know. However, he wonders if the coalescing ideas of masculinity and racial stereotypes have anything to do with it.

“I’m not sure if the media saw an opportunity to see what they thought a masculine person was and what a masculine person should be,” Te’o said. “I think we all get caught up in what we think things should be, not how they are. And I think that gets us in trouble a lot as a society because we start placing our beliefs on somebody else and expecting them to react and act in a certain way.”

“I hope that when they see it and they see me and they see me going through what I went through, all they see is a person that could have responded in a very negative way but actually practiced what he preached about having the aloha spirit.”

Te’o on what he hopes to show polynesian kids.

Prevailing stereotypes around Samoan men, he said, often resemble The Rock — a sort of masculinity that hinges on muscular, physical features. And he said he didn’t feel that he necessarily fit in those strict standards. However, he emphasized that his personal definition of what it means to be a man is incumbent on emotional strength.

“I think people have a false narrative, a false interpretation of what masculine is, I think some people think more masculine is this ‘Incredible Hulk’ figure,” he said. “I think the most masculine person, male or female, is somebody that really can take a lot and not break and be able to still function at a very high level with showing as much compassion as they can and understanding and humility.”

Today, Te’o life is good, he said. The linebacker, who’s now based in Utah, is enjoying time with his family and has a child on the way. In the years since, he’s been focused on healing and discovering who he is, removed from outside validation. It’s something he admits he “fed” off of in those days. He’s had an unorthodox trajectory, but he said he still hopes to be a role model, particularly to Pacific Islander kids, who have seen his story.

“I hope that when they see it and they see me and they see me going through what I went through, all they see is a person that could have responded in a very negative way but actually practiced what he preached about having the aloha spirit,” he said. “About him choosing to love them rather than hate.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com