MIAMI — After seeing three of his closest friends in Cuba receive prison sentences after planning a protest in a WhatsApp group, Alex, 25, decided it was time to leave.

“Someone had already warned me I would be next,” said Alex, who spoke on condition of anonymity since he fears his statements could have repercussions for his family in Cuba.

Alex, from the central province of Sancti Spiritus, said he and a friend booked a flight to Nicaragua in early January, and they made their way to the U.S.-Mexico border using apps like Zenly and Maps.me to guide them.

Alex is part of a growing exodus from Cuba that is on pace to break records. During the six-month period between October and March, nearly 80,000 Cubans were apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border. The number of Cuban migrants crossing the border in March outpaced those arriving from Central America. Senior U.S. officials previously told NBC News they are largely unable to deport Cubans because their government refuses to take them back.

While relations between the U.S. and Cuba have deteriorated over the past several years, officials from both countries are set to meet Thursday in Washington to discuss the spike in migration.

“I have never seen anything like this, and I have been doing this for 30 years,” said Oasis Peña, who works with different organizations, including Integrum Medical Group and the Immigrant Resource Center, that aid and advise newly arrived families on available resources. “We’re seeing a new generation of Cubans without family or contacts here.”

Experts expect the number of Cuban migrants to continue to increase as the Biden administration prepares to lift Title 42, a public health rule that has allowed U.S. authorities to expel migrants seeking asylum.

Cuba largely blames the U.S. for the spike in migration, saying ongoing economic sanctions as well as the closure of the Havana embassy’s consular section encourage Cubans to seek alternative forms of migration. For the past few years following the downsizing of the embassy during the Trump administration, the U.S. has not been processing the 20,000 annual migrant visas it agreed to almost three decades ago.

Cuba is in the midst of a severe economic crisis, with shortages of food and medicine as well as soaring inflation. U.S. sanctions, tightened under former President Donald Trump, aggravated Cuba’s economy. The pandemic also hit the island hard: Cuba shut its borders for eight months and has struggled to boost tourism since reopening, though it has received praise for containing the spread of the virus and for developing its own vaccines.

The dire economic situation led to islandwide protests in July that were followed by a heavy crackdown and mass trials with stiff prison sentences for some of the protesters.

Like in years past, many of the Cubans leaving are young, worrying many about the demographics of the island. The population size is decreasing, while the percentage of older people is growing. In Florida, the wave of migration injects new life into the already established Miami culture and will continue shaping politics for years to come.

‘This is desperation’

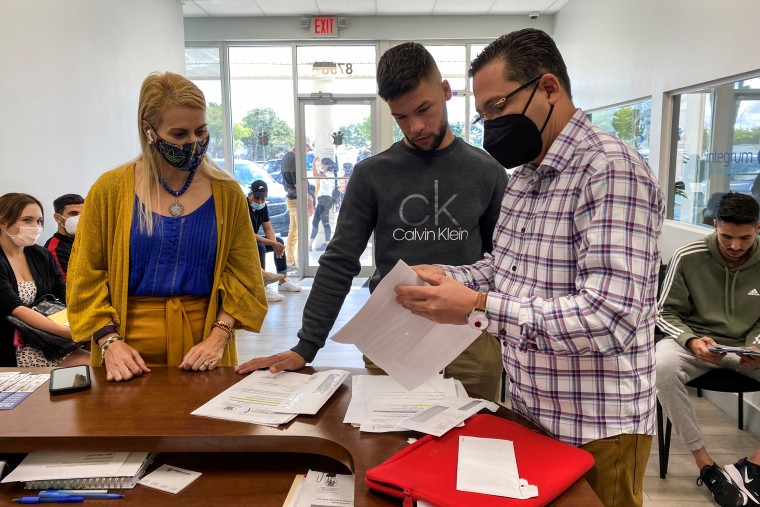

Outside Integrum Medical Group, which provides medical services and community help in conjunction with the Florida Department of Children and Families, newly arrived Cubans began to line up during overnight hours or even the evening before.

“After February, there has been an explosion here,” said Dr. Raul González, one of the group’s owners. “This is desperation.”

González said he is seeing increasingly younger Cubans, around 18 or 19 years old, seeking services. Though the center opens at 7 a.m., González said he has been arriving at 5 a.m. to a line of Cubans waiting outside and leaving work past 8 p.m. A recently arrived family that were patients of González’s in Cuba stayed at his home for six months because they had nowhere to go, he said.

Worrying immigration lawyers and advocates is that Cubans are not receiving parole when they are released in the U.S. They said authorities are issuing other types of documents that do not allow them to become residents under the Cuban Adjustment Act. Since 1966, the Cuban Adjustment Act has allowed most Cubans who are admitted or paroled to adjust their status and become residents after a year and a day in the U.S.

The Church World Service, a nonprofit organization focused on refugee resettlement, said the amount of clients seeking its services at offices in Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties has steadily increased, and the majority of the cases are of Cuban migrants.

“The majority of Cubans that we’ve been seeing are not ‘arriving aliens,’ which means that they have to be in removal proceedings and only a judge can adjudicate their case,” said David Claros, managing attorney at the Church World Service.

Claros said Cubans have been issued different documents when they are released from detention and it has been “inconsistent.” He said it’s complicating the cases, and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services has been denying Cubans’ requests to adjust their status.

“This has been confusing and frustrating for attorneys,” Claros said. “It has led us to creative ways to argue and fight for identifying documents for parole.”

Claros said family units that have entered since May have had their cases processed more quickly, in an effort by the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice to be more “efficient.” But he said the 300 days it takes from the first hearing is not enough for families to prepare evidence and retain adequate counsel — and doesn’t give them time to have their application adjudicated by a judge.

González, the doctor, who said it’s unfair to allow migrants into a country but not give them a legal status that allows them to work, among other things. “If you’re going to let all these people into the country, please let them work,” he said.

The increase in migration is reminiscent of previous waves such as the Mariel boatlift in 1980 and the Cuban rafter crisis in 1994. During the latter, Cuba was also in a deep economic crisis following the collapse of the Soviet Union, which had heavily subsidized the island.

Following an unusual protest in Havana, Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro announced that whoever wanted to leave could go. That led to a “rafter crisis,” and over 35,000 Cubans reached U.S. shores on flimsy rafts and boats. An unknown number died at sea. That led to migration talks between the U.S. and Cuba in which the U.S. agreed to issue 20,000 migrant visas per year and both sides pledged to guarantee safe, orderly and legal migration.

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com