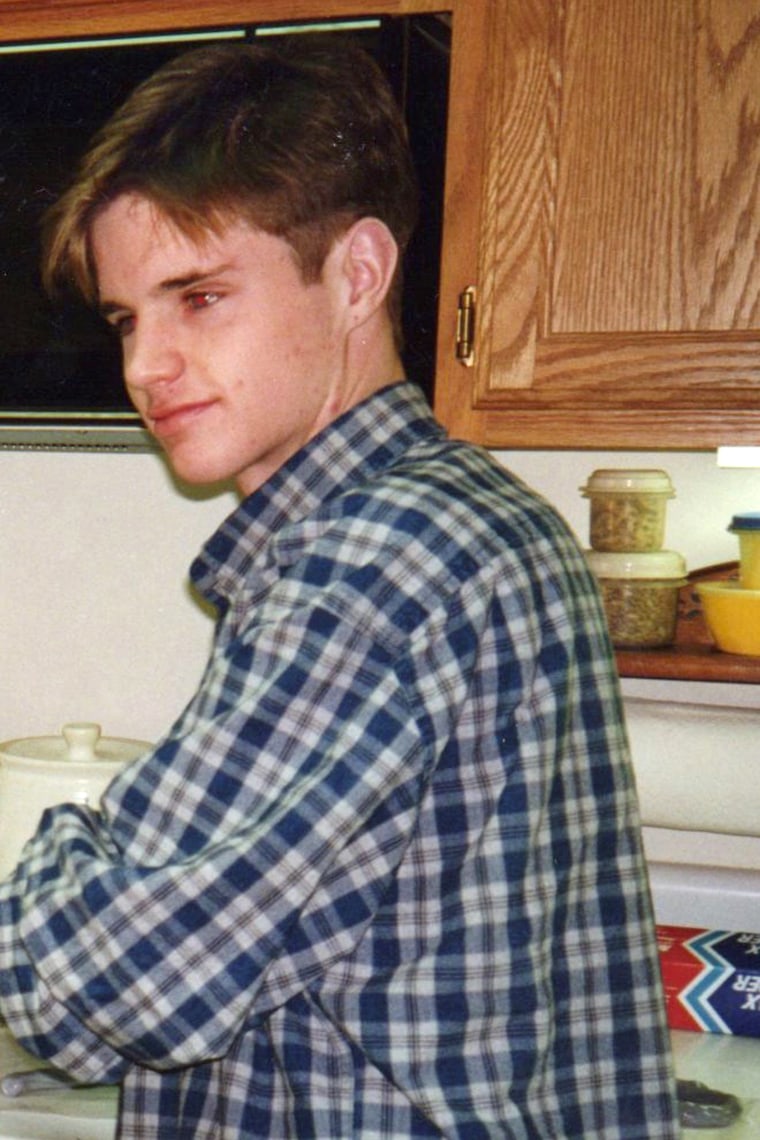

It’s been 25 years since Matthew Shepard, a gay 21-year-old University of Wyoming student, died six days after he was savagely beaten by two young men and tied to a remote fence to meet his fate. His death has been memorialized as an egregious hate crime that helped fuel the LGBTQ rights movement over the ensuing years.

From the perspective of the movement’s activists — some of them on the front lines since the 1960s — progress was often agonizingly slow, but it was steady.

Vermont allowed same-sex civil unions in 2000. A Texas law criminalizing consensual gay sex was struck down in 2003. In 2011, the military scrapped the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy that kept gay, lesbian and bisexual service members in the closet. And in 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriages were legal nationwide.

But any perception back then that the long struggle for equality had been won has been belied by events over the past two years.

Five people were killed last year in a mass shooting at an LGBTQ nightclub in Colorado. More than 20 Republican-controlled states have enacted an array of anti-LGBTQ laws including bans on sports participation and certain medical care for young transgender people, as well as restrictions on how schools can broach LGBTQ-related topics.

“Undoubtedly we’ve made huge progress, but it’s all at risk,” said Kevin Jennings, the CEO of Lambda Legal, which has been litigating against some of the new anti-LGBTQ laws. “Anybody who thinks that once you’ve won rights they’re safe doesn’t understand history. The opponents of equality never give up. They’re like the Terminator — they’re not going to stop coming until they take away your rights.”

Some of the new laws are directed broadly at the entire LGBTQ community, such as Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law, which imposes bans and restrictions on lessons in public schools about sexual orientation and gender identity. But in many of the GOP-governed states — including Florida — the prime target of legislation has been transgender people.

In addition to measures addressing medical treatments and sports participation, some laws restrict using the pronouns trans students use in classrooms.

“What we’ve said in Florida is we are going to remain a refuge of sanity and a citadel of normalcy,” said Gov. Ron DeSantis as he signed such bills earlier this year. “We’re not doing the pronoun Olympics in Florida.”

Shannon Minter, a transgender civil rights lawyer with the National Center for Lesbian Rights, depicted the wave of anti-trans bills — in some cases leading to legal harassment of trans people — as the one of the gravest threats to the LGBTQ community in his 30 years of activism.

“We are in danger now, given the ferocity of this backlash,” he said. “If we don’t stop this with sufficient urgency, we’ll end up with half the country living with very significant bias and lack of legal protection.”

Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality, depicted the legislative attacks as “the backlash to our progress.”

“We made so much progress as an LGBTQ movement, at a fast pace compared to other social justice movements,” he said. “You do have a minority who is overwhelmingly upset by it. They are fired up and they are well-resourced.”

Heng-Lehtinen is optimistic for the long term but said that right now, “trans people across the country are really struggling with feeling any kind of hope.”

The key to changing the current dynamic is for more people in GOP-governed states to get to know and understand trans people, said James Esseks, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s LGBTQ & HIV Project.

“But the efforts of the other side are designed to stop that from happening,” Esseks said. “They want trans people to disappear — no health care, can’t use public restrooms, can’t have a government ID consistent with who you are, and the schools can’t teach about the existence of trans people.”

Esseks reflected back to the Supreme Court’s historic same-sex marriage ruling in 2015. At the time, he said, many activists were thinking elatedly, “OK, we’re kind of done.”

“But the other side pivoted to attacking trans people and seeking religious exemptions to get a right to discriminate against gay people,” he said. “Both of those strategies, unfortunately, have been quite successful.”

Related stories:

The president of the largest national LGBTQ rights organization, Kelley Robinson of the Human Rights Campaign, summarized the situation on Tuesday:

“LGBTQ+ Americans are living in a state of emergency — experiencing unprecedented attacks from extremist politicians and their right-wing allies in states across the country, who are working tirelessly to erase us.”

Several activists interviewed this week by The Associated Press evoked Matthew Shepard as they discussed broader developments. His memory lives on in many manifestations, including:

— The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, signed by then-President Barack Obama in 2009. The act expanded the federal hate crime law to include crimes based on a victim’s sexual orientation, gender identity or disability.

— “The Laramie Project,” a play based on more than 200 interviews with residents of Laramie, Wyoming, connected to Shepard and his murder. It is a popular choice for high school theater productions but has faced opposition due to policies resembling Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law that have surfaced in various states and communities.

— The Matthew Shepard Foundation, a nonprofit co-founded by Shepard’s mother, Judy. Its self-described mission: “To inspire individuals, organizations, and communities to embrace the dignity and equality of all people … and address hate that lives within our schools, neighborhoods, and homes.”

“Matthew Shepard’s death was a life-altering moment for a lot of people,” said Shelby Chestnut, executive director of the Transgender Law Center.

Earlier in his career, Chestnut worked with the New York City Anti-Violence Project, an experience that influences his worries about the recent anti-trans bills.

“When you create conditions where people have lack of access to jobs, to health care, they’re more likely to be victims of violence,” he said.

The communications director of the National LGBTQ Task Force, Cathy Renna, was in the early stages of her LGBTQ activism when she became involved in media coverage of Shepard’s murder in 1998.

“It shapes the way you do your advocacy for the rest of your life,” she said. “It got many people involved. It was a lightbulb — realizing that hate crimes are a thing that happens.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com